Let Me Consider It From Here: The Renaissance Society

by Ryan Filchak

Once a street is well equipped to handle strangers, once it has both a good, effective demarcation between private and public spaces and has a basic supply of activity and eyes, the more strangers the merrier. —Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Curated by Solveig Øvstebø, this latest exhibition at the Renaissance Society brings together sound, painting, and sculpture to address the peculiar middle ground that exists between public and private space. As a result, the four artists included in Let me consider it from here inadvertently challenge the axiom that all art is political. The lines drawn from Saul Fletcher, Brook Hsu, Constance DeJong, and Tetsumi Kudo do not trace visual similarities but instead weave a thick, dense fabric of the personal and of language. Spanning multiple decades and backgrounds, through this exhibition each artist shares powerful examples of how to control their movement within and across these spaces.

Saul Fletcher’s photographs read as a line of free form poetry, economic in word choice, unconcerned with a sonnet’s structure. “Untitled” can often stand in for the mysteries of composition, but Fletcher is working to reveal himself through the literal lens of a camera. Studio tableauxs and portraits provide the viewer a glimpse of Fletcher’s personal narrative, but that which we can see comes as a result of careful deliberation. These pieces act as telescopes focused on fixed points. Distance and caution make up the language of Fletcher’s work, but the striking images invoke curiosity, and the moves made between his private studio and public participation garner the viewer’s undivided attention and respect.

Tetsumi Kudo (1935-1990), best known for his brazen public works most often associated with the Anti-Art and Neo-Dadaist movements of the 1950s and 60s, acts as the godfather of this otherwise unlikely group. The only artist not living, Kudo has received an art historical reappraisal in the last decade in part due to his increasingly understood influence on Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley. Ironically, Kudo’s reassessment and praise of the last decade stems from his relatively less confrontational works after he moved from Japan and began to work in a Paris studio. During this time, Kudo’s practice ceased addressing the global political anxieties of post-war Japan and instead shifted inward to self-portraiture, introspection, and sculpture.

Through elements of kitsch and outsider art, the seven highly representative sculptures on display at the Renaissance Society provide a glimpse into the creator’s own despair of personal erosion. Fragmented anatomical forms, often phallic, commingle with brightly colored accessories in aquariums and bird cages. The works in Let me consider it from here were never shown in the United States during Kudo’s lifetime, and for this reason alone his posthumous resurgence seems understandable. These surrealistic moments of inner turmoil find a linkage both apolitical and universal that foreshadows the current contemporary climate, wordlessly speaking a language of concern artist Brook Hsu grapples with in a powerful way.

Hsu’s intensely candid and generous work takes note of Kudo’s legacy and resolves the inevitable maintenance of the conflicting public and private life of an artist through alternative measures. “It’s not something I really talk about, but creating a space for spiritual practice in art making is something I care for deeply. Mythical figures such as the ancient Greek god Pan and fairies serve the role of what I call a “spiritual surrogate”, a god that I can relate to,” Hsu said in an interview with Elephant. Kudo left performance in favor of an isolated practice, where as Hsu engages through methods that hope to intercept misrepresentation.

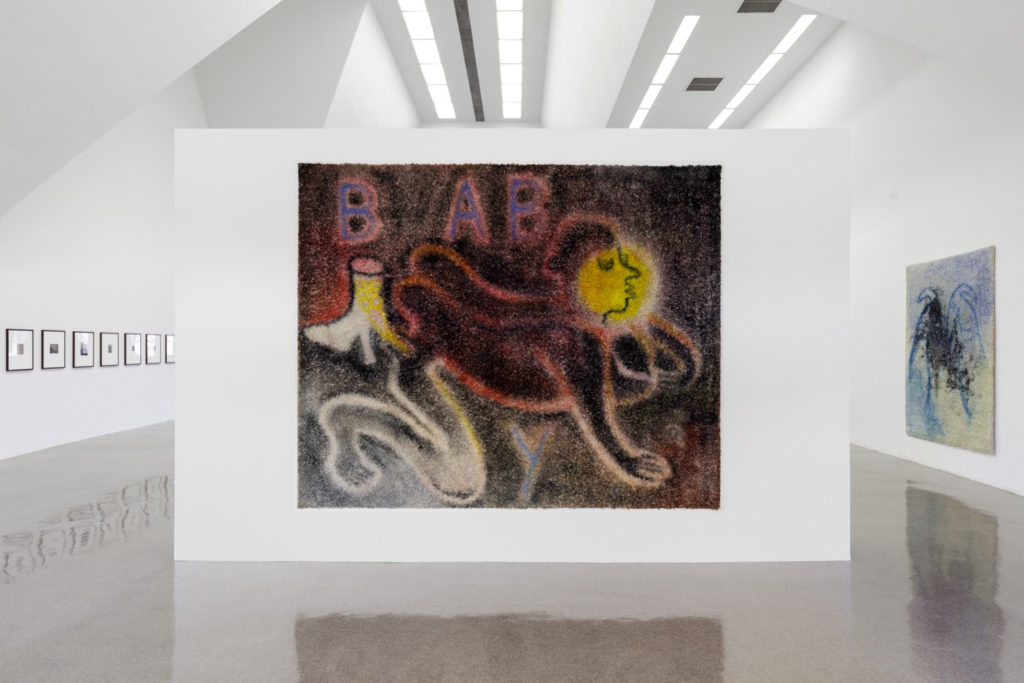

Hsu’s large works of acrylic on store-bought carpets best serve this self-prescribed process of self-mythologization. Spanning two white painted carpets, Hsu’s particularly stunning piece Earth Angel (2017) depicts one of these such “spiritual surrogates.” In red outline, a human form in the flexible crouch of a four legged animal looks behind itself onto a backside that invokes a watermelon patch. Blue flowers and vines overlap the figure, spanning the height and width of the piece. The bizarre and pleasant imagery links Hsu to Kudo, but her material choice gives credence to the stains that do not share the same lines as the figure or the fauna. Her gods have been stepped on.

Fortunately for these artists, they have found spectacular company and each share the valiant effort to pursue the ways in which language—visual or otherwise—can cure what ails us. Dejong’s audio pieces attest to these efforts. From the Nightwriters series, these four monologues recall the restless nights of sleepwalkers. The audio pieces explore the language of the subconscious and the personal space that which their speakers can not control. Unlike the other three artists whom rely on a developing aesthetic, Dejong’s work deals with a loss of control over, and not the maintenance of one’s public and private self.

Despite these artists attempts to craft their own careful patterns of movement between these two worlds, the Renaissance Society remains a crowded room. Not crowded in the sense of an exhibition superfluously hung, but crowded in a way that effectively imitates and critiques the current informational zeitgeist. Best laid plans of control must inevitably compete with the plans of others, and for those maintaining a specific personal agenda, this leaves only a future of uncertainty. However, these artists, in each their own way, prove this quest for personal agency, an agenda well worth our consideration.

Let me consider it from here runs at the Renaissance Society until Jan. 27, 2019.