Looking Westward: A Chicago Artist Returns Home

by Kate Pollasch

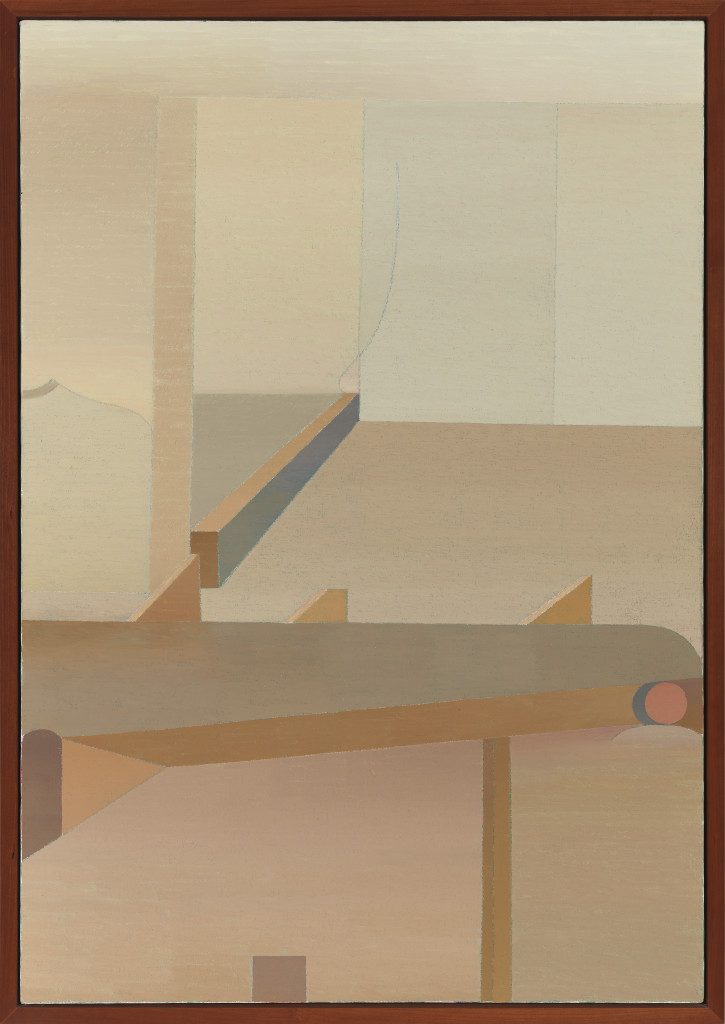

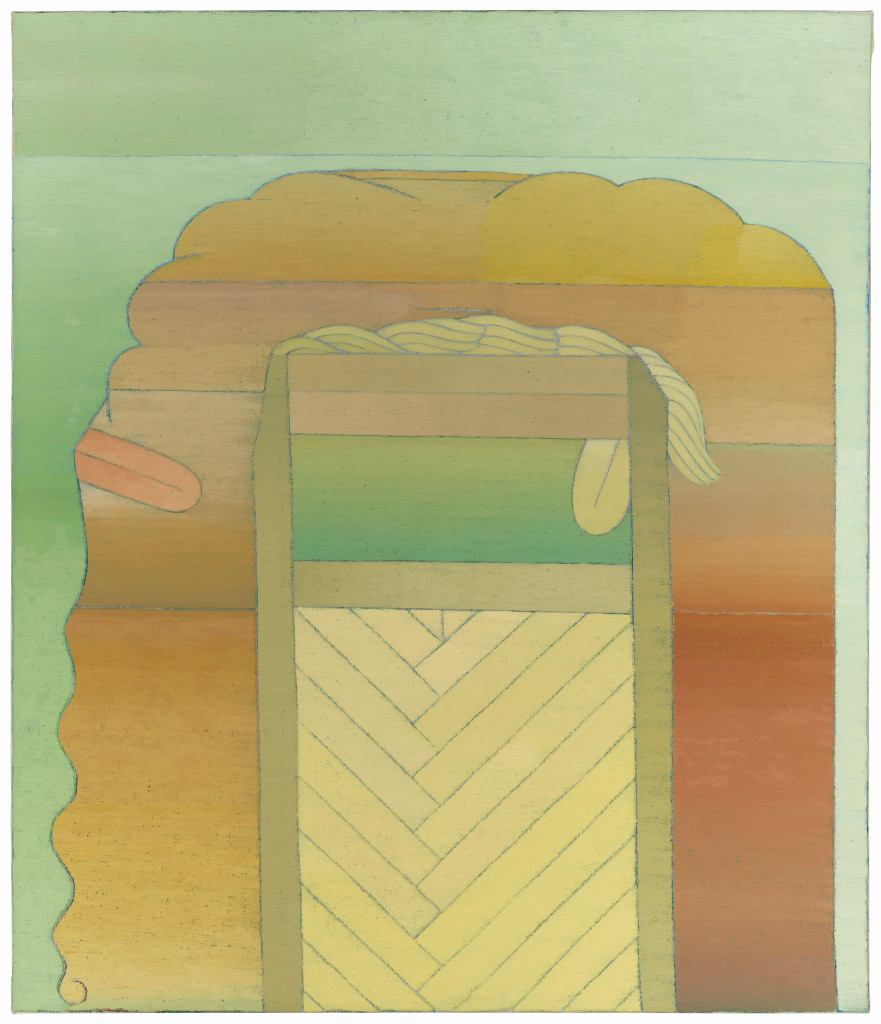

Most of us have experienced one artist whose works make words feel inadequate; who creates topographies and compositions that leaves one beguiled in a haze of unending attraction and questions, lost for a way to emote the magnetic complexity of their work. For me, this artist is Miyoko Ito (1918–1983). Born and raised in Berkley, California, Ito received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of California in 1942. She spent a brief time in a Japanese Internment camp in California during World War II and relocated to study at Smith College before moving to Chicago to attend The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1944. Once she moved to Chicago, Ito would remain and build her practice until her death in 1983. Ito is not the most well-known Chicago painter, but her decades long career left behind a survey of works that suspend reality, awaken a scene of saturated color, illogical space, and mysterious corporeal references that echo with subtlety and self-assurance. Her canvases are resolved and commanding, generously offering a choreography between macro forms and micro gestures.

Ito was an abstract artist whose compositions signal architecture, furniture, domestic space, and bodies with keen deconstruction and ambiguity. Each scene is charged with reverberating inconsistencies; what might seem like a drawer is also touched by thin wisps of hair and what might feel like a threshold is pushed back by a flat sense of space. Working through the times of the Monster Roster and Chicago Imagists, Ito was an abstractionist in a swirl of thriving and popular representational Chicago artists. Represented by Phyllis Kind Gallery and exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center under Curator Don Baum, she was also an inspiration to many of the younger Imagist artists—such as Jim Nutt, Roger Brown, and Gladys Nilsson. On a larger national platform, her ingenious approach to geometric and organic formal construction paired with decades-long shifting color pallets places her in the center of a constellation of innovative abstraction artists. But, historically she has remained siloed from these art historical discussions, left off the debate of modern abstraction and not the exact fit for the study of Imagists art history. Her works can be found in prominent private collections more than they are in museums across the nation, and historical texts are thinly evident throughout the decades.

But time is not Ito’s enemy—her work does not stand on the accolades of the past, or on the popularity of art history. Her paintings remain, unapologetic in their expertise, waiting to imprint themselves on any who will view. San Francisco-based Curator Jordan Stein, has spent the past two years exhuming Ito’s works from collections and closets across the nation to create the exhibition Miyoko Ito: MATRIX 267 at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. The first solo exhibition of Ito’s work in Berkley and the first exhibition of her work in a public context in nearly forty years, this exhibition brings Ito home to California, and back into a contemporary context. I had the opportunity to speak with Jordan Stein about his approach to curating, research into Ito, and views on her work. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

Kate Pollasch: The exhibition, Matrix 267, was quite a historic undertaking as the first solo presentation of her work in Berkeley and also the first in a public institution in about 40 years. As you began developing this exhibition, how did you navigate her place in art history and Chicago history, in Berkeley, California?

Jordan Stein: In terms of her place in Berkley, well, Miyoko has no place in Berkeley, art historically speaking. She was born and raised there, where she was also an art major at Cal [The University of California, Berkley]. But she did not emerge with a unique style or clique: I got the impression that she was quite studious, enjoyed the limited socializing the art department afforded, and worked almost exclusively in a watercolor tradition known as synthetic cubism. Broadly speaking, as her career advances the pallet warms up and the compositions become more bodily. Her paintings look more and more “California” in terms of the vistas and colors and embodied self-searching. I think they represent the mind of an artist who is moving Westward in her imagination—moving homeward, really.

The strongest feedback I’ve been getting about this show is from artists, mostly painters. It has been conjuring a lot of superlatives, which is fantastic, but I can’t precisely put my finger of why it resonates so deeply in the Bay area at this moment. I suppose it has something to do with the wild yet mannered abstraction at the heart of her practice, one that breaks as many rules as it makes. She is not really a California artist, but this notion feels very California to me.

In terms of Chicago history, it makes good sense that Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, and other now-celebrated artists of that generation were tremendously inspired by her work; it presages many Imagist preoccupations. But it perplexes me that she is the first abstract artist that Phyllis Kind (founder of Phyllis Kind Gallery) picks up. We know that it was Kind’s husband, an art historian, who suggested that she pay attention to Ito—a move that inspired a host of younger artists to sign up with Phyllis, too. In many ways throughout her life, Ito is very isolated, not really a solid member of any school of group. She did not have a gang and should not exactly be written into Imagist history. I suspect it may be important to an understanding of the work, and Ito’s place in Chicago, to acknowledge that she was somewhat placeless. This suited my approach quite well as I am not an art historian, not a Chicago specialist. It felt appropriate coming to the work as an outsider. I should note that although she is a hero to many local artists, the work is largely unknown outside Chicago.

KP: Yes, your approach really lets the work stand and speak for itself in a very timeless manner. Whereas, if you had been so focused on pigeonholing her into a certain category or trying to find some context to relate her artistic growth and decisions off of, which is a great art historical gesture when it needs to be done, but it is very freeing to simply look at this woman’s incredible trajectory and complex practice without any outside grouping. Then, to acknowledge the time period that she has been working in without feeling so bound to say “well I am going to reposition her with one group, or I am going to take her out of another group,” is a very open approach.

JS: That is nice to hear. The only group she needs to be associated with at this moment is a room full of her paintings. This lets a view feel the juxtaposition of wide open spaces with a kind of imprisonment and isolation. Her work appears in group shows throughout the seventies and eighties in Chicago and beyond, and even the Whitney Biennial, but it just did not hit like it might have in solo exhibitions.

KP: There is a very careful balance that you walk in your exhibition essay between addressing Ito’s biography, and the impact that may have had on her practice, and her formal and conceptual interests as a working artist. I am curious what your approach is to biography as it relates to addressing or interpreting an artist’s artistic choices? Did you find that Ito’s work was rooted from a place of self-reflection and personal biography, or was she working from a different place–perhaps more engaged in the art world dialogue of abstract art?

JS: My guess is that nearly 100% of folks seeing this exhibition have never heard of Miyoko Ito. Not only that, but she’s from Berkley and has been gone for decades. I felt like I needed to do my job in introducing her, providing an overview of her life. Additionally, I think certain chapters of her life story graft onto the work in a useful way. And I didn’t want to position her as exclusively an outsider, so it was important to mention artist friends like Thomas Kapsalis and Evelyn Statsinger, people making great work around her at SAIC and after.

I happen to be partial to a kind of narration akin to storytelling. What I tried to do in the exhibition text is toe the line between what I think someone should know about her life and analysis of the work. I wanted to be a biographer and historian at the same time.

KP: Right. You acknowledged early on that there was some leg work that needed to be done and a context that didn’t have a public presence. In a sense, you are doing the first show there, so you need to introduce her in a way that lays a foundation.

JS: Yes, I felt a little uncomfortable diving straight into what we are looking at. I hope future shows of her work will do that.

The cards could have fallen in a number of different ways. At the start of my research, I didn’t know what was available; I had seen two paintings in person and wondered what else was out there. In collaboration with the museum in Berkeley, we decided that this was well positioned as a Matrix exhibition, which has a long history of serving as a jumping off point for emerging and lesser-known artists. This isn’t a retrospective, so there’s a deliberate through line to the chosen works. I was consistently drawn to a curious shape, something like a traditional bust, with shoulders, that appears in her work—this resonated with me as a practice of self-portraiture. That said, Miyoko remained fairly elusive in this process. I felt like I was seeing her but not quite seeing her, always finding her back or her shadow, traces of how she saw herself.

KP: That is why her work has always felt so moving to me, those pieces do speak for themselves, and you need nothing more than to get lost in them. But as you keep unfolding the layers of her history, of her community, and the time in art history, the work only gets more mysterious and there is only more to explore.

On that note of biography, Ito’s history is quite complex and one thing that I have always wanted to reflect deeper on is her experience at the Japanese Internment camp in California in relation to the imagined, often insular and intimate, creation of space that she created throughout her career. To have one’s liberties, freedom of mobility, privacy, and sense of national identity stripped for a period of time is a very transformative experience. Furthermore, as a child she was very sick and bedridden for extended periods of time. I cannot help but wondering if these experiences in physical containment and limitations speak to the free and abstract way she was able to render illogical spaces and dream like scenes? When the body can’t move as it pleases, then one can escape through their mind. As you navigated these chapters in her biography how did you place them within the understanding of her artistic voice?

JS: That is very well stated. Let’s note, for starters, that she was not big on speaking of the work in biographical terms. In one of the few interviews with her that exist, she recounts how her friend, the great artist Ray Yoshida, once suggested that the Heian period of Japanese painting must have been very important to her. And she says something like, “and so it was.” Influences were welcome, but deliberately unconscious. This is really attractive to me, how she approached painting as a process of invention and reinvention. But, of course, we all carry our pasts with us and in this case her life provides a legible tension between a crippled hauntedness and the endless gaze she is so good at rendering. I didn’t want to communicate this too directly, but allow visitors to fill in the blanks. I think it becomes clear that painting was her lifeline—her way of reconciling the many subjects of your question.

KP: Yes, there is that really distinct quote that you have in the beginning of your essay where she compares painting to living, this is the way she connects to the world. Whether she was simply channeling the tensions of space, confinement, and constraint in an abstract work on the canvas or weather she was more literally working through her biographical understanding of constraint or confinement–either way–the work emotes those sensations in a powerful way throughout her entire career.

JS: These paintings not only depict distant horizons, but complicated networks of views within views, lots of ways to get lost. The beautiful gradient work, the underpainting, the drawing, the stacking tubes and bars—it is a lot more than the sum of its parts. In her life, much was out of her control; she was forced to physically and mentally submit to oppressive and unfair circumstances. Painting became like breathing, the only place she could reliably take herself. That’s really something. Painting not only as a place, but the only place. This is someone who is not screwing around when they go to work every day.

KP: For me, the generation of artists that Ito was working alongside and in Chicago feel more and more on the pulse of our contemporary everyday life. They were gritty self-starting artists who didn’t wait for recognition from some higher cannon of art but built their own world in the face of struggle and trials. As you reflect on this exhibition, and showcasing an artist who has long been missing the dues that she deserves, what do you hope and see for Ito’s role in art history and contemporary art.

JS: I agree, and it is an approach that is harder and harder to come by, sadly. It is a weird feeling to have hopes and dreams for someone who has been gone for so long, but it is amazing that so many young painters are knocked out by this show. She loved trading art with other artists; to her, this was tops. So I hope the work is folded back into contemporary conversations about abstraction, anguish, beauty, strangeness, reckoning, self-portraiture, and grace.

KP: She is an artists’ artist, it is not like she was in it for some other purpose, for her it was the 7 days a week everyday life, and I think the show mirrors that—it is a celebration of the work and the power of her work.

Miyoko Ito: MATRIX 267 runs through January 28, 2018 at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.