Manifesta 11 & Francis Picabia: Kunsthalle Zürich

by Terry R. Myers

Who doesn’t want a partner in crime? Before arriving in Zürich this summer for the opening of Manifesta 11, I hadn’t thought too much about the rich harmonic (and, better yet, dissonant) convergence that would come from pairing the latest version of “The European Biennial of Contemporary Art” with a Francis Picabia retrospective that opened at the Kunsthaus Zürich just a few days before (it will travel in November to MoMA in New York). The story goes that one of the key reasons that Zürich was chosen to host Manifesta 11 was because 2016 is the centennial of the city’s contributions to the Dada movement. The story of Zürich Dada is fantastic, even epic, full of antics and misadventures, refusals and resistance, friends and enemies, and the lasting impact of some killer works of art—none more devastating (in the best way) than some of Picabia’s from the early period of his far-reaching career. What could be better for accompanying yet another international biennial than the lasting edge and high energy of Dada, as represented in the work of artist who kept on going? Talk about an opportunity.

“I’ve got the brains, you’ve got the looks. Let’s make lots of money.”—Pet Shop Boys, “Opportunities (Let’s Make Lots of Money),” 1986

Picabia’s exhibition is a triumph and Manifesta was not a disaster. Unprepared for the level to which the sustained energy of the former would overwhelm the substantial ambitions of the latter, the two exhibitions demonstrated the skewed relationship between the general and the specific in contemporary art today. I spent the afternoon before the Manifesta press preview with Picabia; by the time I got to the second room, I was already berating myself as to why the exhibition had not figured in my plans to cover the biennial—perhaps I was too focused on the surprising selection of an artist, Christian Jankowski, as its curator. The surprise was not that it was him, but that an artist was selected at all. Though, given Jankowski’s perpetual collaboration with those “outside” the art world in his own work, he has kept the door open for such an invitation since the beginning of his career. This is not a negative assessment—rather, following Jankowski’s work over the years has more often than not been engaging. During the press conference, I asked what he would think if some of us came away concluding that Manifesta was in fact the largest Christian Jankowski work of art to date. Like most good artists, he sidestepped the question very well.

Overall, the exhibition, refreshingly subtitled What People Do For Money, kept to its criteria. Its core section, The Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction, co-curated with Francesca Gavin, made an admirable attempt to be as broad as possible, setting a wide range of historical art works alongside new commissions, most of which were presented in the “white cube” spaces of the Löwenbräukunst and the Helmhaus. At its best, it pulled double duty by setting up the remaining components of Manifesta spread out across the city by creating moment after moment of varying “collaborations” between works of art rather than artists, in pairings such as Andreas Gursky’s photograph Karlsruhe Siemens (1991) and Trevor Paglen’s NSA-Tapped Undersea Cable, North Pacific Ocean (2016). Alternately, in an observational collusion, the exhibition made the extra-meta move of bringing Sharon Lockhart’s multi-part photographic mural Lunch Break Installation, ‘Duane Hanson: Sculptures of Life,’ 14 December 2002-23 February 2003, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 2003 (2003) face to face with its “real” thing, Duane Hanson’s hyperreal sculptural tableau Lunchbreak (1989). While presented mainly on a scaffold-type structure across the many spaces, the historical component did not overtake the presentation of the strongest new works commissioned for Manifesta. These included Mike Bouchet’s The Zurich Load (2016), 80,000 kgs of sludge made from one day of Zürich’s human waste and presented as a set of eye-nose-and-throat stinging black cubes; and Carles Congost’s faux-documentary film Simply the Best (2016), done in collaboration with members of the Zürich Fire Department, about a fictional fundraising concert that would star Tina Turner and provide the city a new slogan. Striking a perfect balance of fantasy and labor, the film not only satisfied the exhibition’s theme, but also likely became even more resonant in its simultaneous presentation in a fire station in the city.

Of the thirty “satellites,” where each artist brought the work they made back to the territory of their collaborators, those that I did visit paid off: The World is Cuckoo (Clock) (2016), Jon Kessler’s elegant and mad kinetic sculpture, churning in the working basement of a high-end watchmaker’s shop; Muthoscapes (2016), Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s poetic installation of paintings in the display cases of the central station tourist office that depict the Swiss Alps “excavated,” with the help of a conservator, to reveal the mythical lost continent of Mu, thought to have been a cradle of several civilizations; and, quite directly, Halbierte Western (Halved Vests) (2015-16), Franz Erhard Walther’s bright orange uniform produced for staff at the Park Hyatt (in collaboration with a textile developer) reminiscent of the avant-garde clothing of the time of Dada. (I saw two staff members wearing them in the hotel’s lobby. They did not seem pleased.) Despite the impossibility of getting to most of these satellites, the next component of the exhibition—thirty short films produced by Jankowski, each artist, a filmmaker from the local art school, and a teenage “detective” who was given the task of following each artist—made clear that the satellites were the circulatory system of the exhibition. It seems as if Jankowski was influenced by the historical section of Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Documenta 13 called “The Brain,” located in the center of her exhibition in 2012.

Jankowski’s most brilliant move was the Pavilion of Reflections, a temporary floating island on Lake Zürich, that became the nervous system of Manifesta. Elegantly constructed of wood, it contained a bar, swimming hole, and cinema for the perpetual screening of the aforementioned films. However, while sitting through nearly a third of the screenings over two days, all of which were insightful and even entertaining, Jankowski became too present. This, of course, is something that happens to curators of international biennials all too often—though, here, given that Jankowski’s own artistic production is so dependent upon highlighting the tensions and resolutions between art and, let’s say, life—or artists and others—the films suggest the thin line between an accomplice and a third wheel. Put another way, what good is a partner in crime who always gets in the way?

I left before the last part of Manifesta kicked off: the re-deployment of the Cabaret Voltaire as the home for a new guild for artists, which provided Manifesta a place to go completely off script. In this case, it meant anyone could sign up to give a performance, acknowledging the bar’s history as the place to be for the Dadaists in Zürich, including, for a time, Picabia. (It was a good sign that the antics began with the always-reliable group of tricksters known as Gelatin.) Maybe Jankowski was reminding us that he is an artist, not a curator after all.

I ask again: who doesn’t want a partner in crime? Picabia’s exhibition demonstrates that early on he most definitely did. Like so many other artists of his generation, he started with Impressionism, becoming financially successful while still breaking the rules by relying upon photographs to make his paintings— and then quickly junked it all for Cubism. The exhibition reunites his well-known pair of outrageously over-sized contributions to the genre: Udnie (Young American Girl; Dance) (1913), and Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic) (1913). Picabia then hits Dada head-on, creating so many works of so many types, including paintings, constructions, as well as handbills like Funny-Guy (1921) on which he proclaims: “FRANCIS PICABIA N’EST RIEN!” Despite all of the ways in which he truly was a partner in crime with the other Dadaists, Picabia was already his own best accomplice before moving on to new adventures. This notion, of one being one’s own best co-conspirator, is echoed within the exhibition’s subtitle, borrowed from Picabia himself: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction.

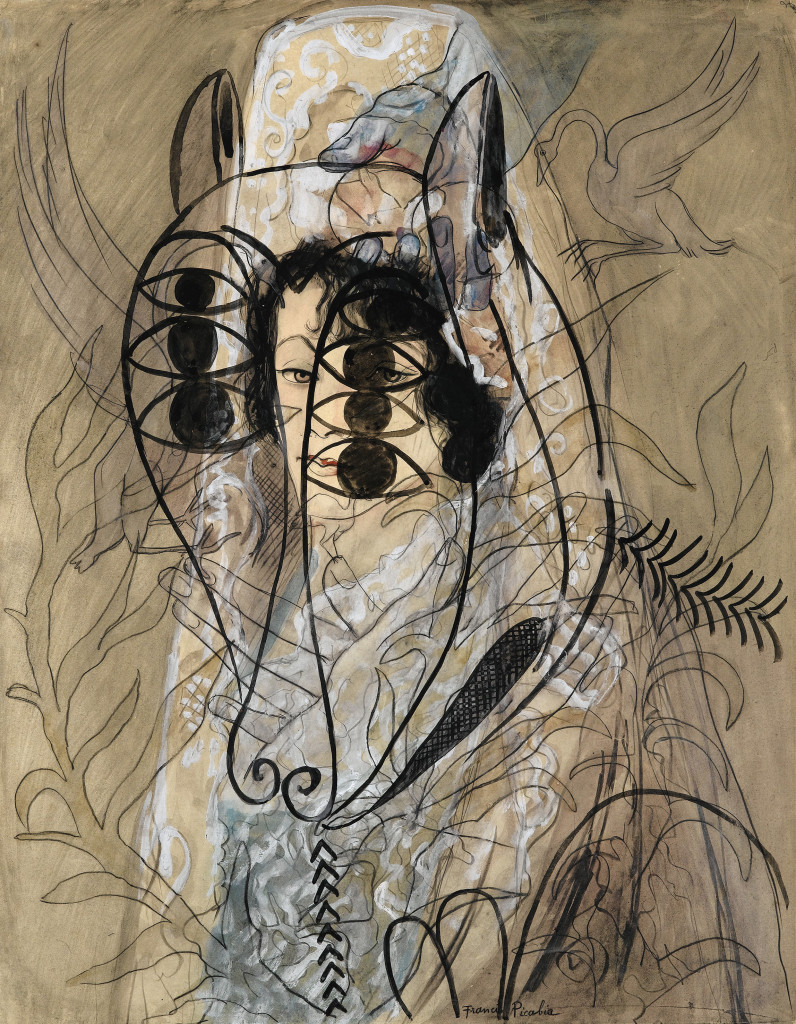

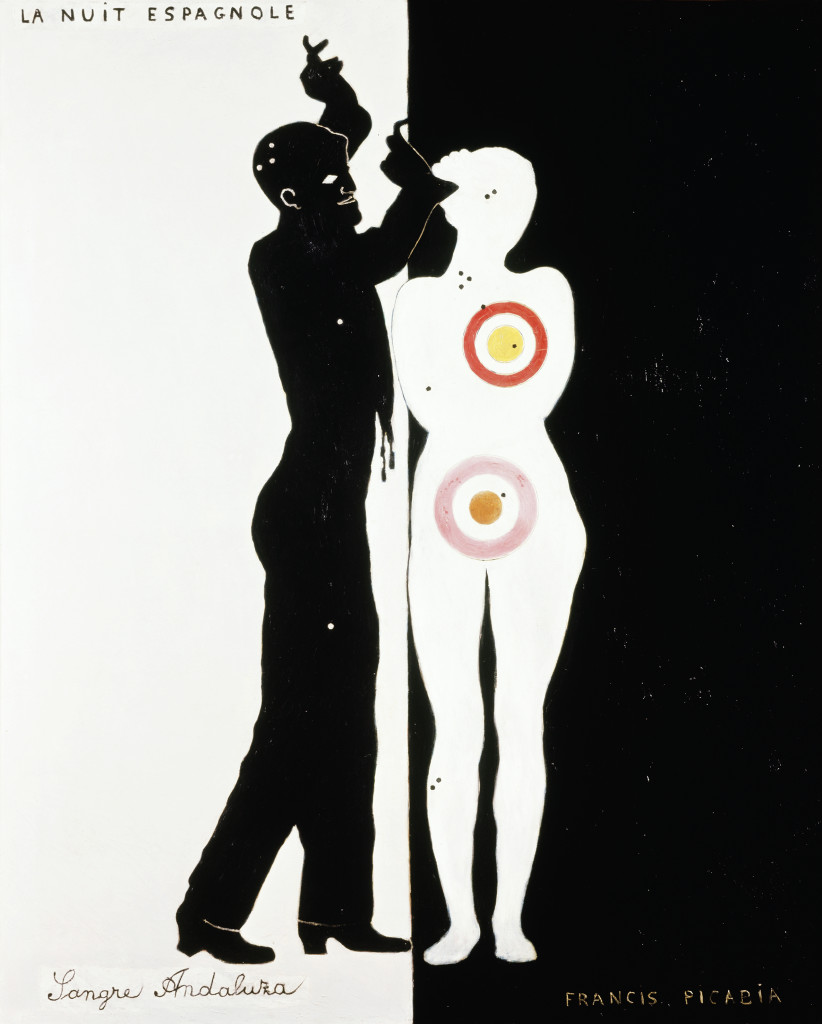

Anyone up on the machinations of modernism and post-modernism is well aware of the consistent ascendancy of Picabia’s reputation over the past three decades. As this exhibition demonstrates, we are just beginning to assimilate the depth of his work’s complexities. To see each decade of his enterprise impeccably presented room by room is to witness genuine staying power. First he resorted to the industrial look and feel of Ripolin enamel paint to “return” to neoclassical forms in paintings such as The Spanish Night (1922) and Animal Trainer (1923). Then he dipped briefly into assemblage with a witty concoction like Toothpicks (c. 1924), and immediately followed up with a group of “monster” paintings like Idyll (c. 1925–27). This work is a pictorial and material mash-up of the prior twenty-or-so years of pretty much every other modernist painting. Picabia outmaneuvered much of Surrealism in works like Untitled (Spanish Woman and Lamb of the Apocalypse) (1927), from his Transparenices series of paintings that takes him through the 1930s, then into the unapologetic kitsch “realism” of Spring (c. 1942-43), and, finally, to the anything-but-pure “abstraction” of what would become his last works, paintings like Selfishness (1950) and the aptly-titled Salary Is the Reason for Work (1949).

This last painting is a star. Arguably, in some ways, a wicked “return” to Dada, the way in which it caps a career that looks today as if it never stopped is nothing short of remarkable. I left the exhibition thinking that even Picasso and Matisse don’t have that today. Duchamp? Maybe. It seems unfathomable that Picabia could have predicted how his ways would become the way for so many. He remains, on his own, a potent challenger to everything from the wishful thinking about the “death” of painting to the shelter of the herd mentality that too often afflicts large-scale group exhibitions. The lesson? Never stop being your own partner-in-crime.

Manifesta 11: What People Do For Money runs through September 18, 2016 and Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction at the Kunsthaus Zürich runs through September 25, 2016.