Mark Wallinger: The Fruitmarket Gallery

by Noah Hanna

It can be challenging to trace the roots of Mark Wallinger’s artwork. The Turner Prize awardee has adopted such numerous personas, mediums, and themes that any attempt to locate the origin of his illustrious career can seem futile—though it appears Wallinger prefers it that way. Sharing the gallery space at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery and Dundee Contemporary Arts, Wallinger’s exhibition only deepens his commitment to a perpetually nebulous practice.

Wallinger views the world as if he possesses its deep secrets, but is more than willing to put his own character on the line to even the odds. Like a two-way mirror that Wallinger holds between himself and society, the product of his work is the source of no shortage of painful, humorous self-awareness; the realization that reality and truth may not be possessed by himself or the world we populate.

Beginning in the 1980s, Wallinger’s obsession with the absurd has taken on manifestations: film, sculpture, painting, and performance, at times dipping uncomfortably deep into politics and the human psyche. This risk would eventually earn him one of England’s highest awards for the arts in 2007. However, Wallinger remains a societal and political observer—like the classic anthropologist, he gazes out from his veranda at the pomp and circumstance of his own English culture.

Despite a considerable career, the exhibition, simply titled MARK, strays from a retrospective format—a decision I will always commend. Rather, Wallinger is presented as an artist who commands the multitude of mediums he employs and avoids the dreadful characterization of an artist whose work now must be remembered rather than engaged. Significant attention is placed on his most recent creations primarily in regards to painting. Wallinger’s id series as well as his tongue in cheek self-portraits hold their own weight and receive a heightened appreciation when placed in juxtaposition with past favorites.

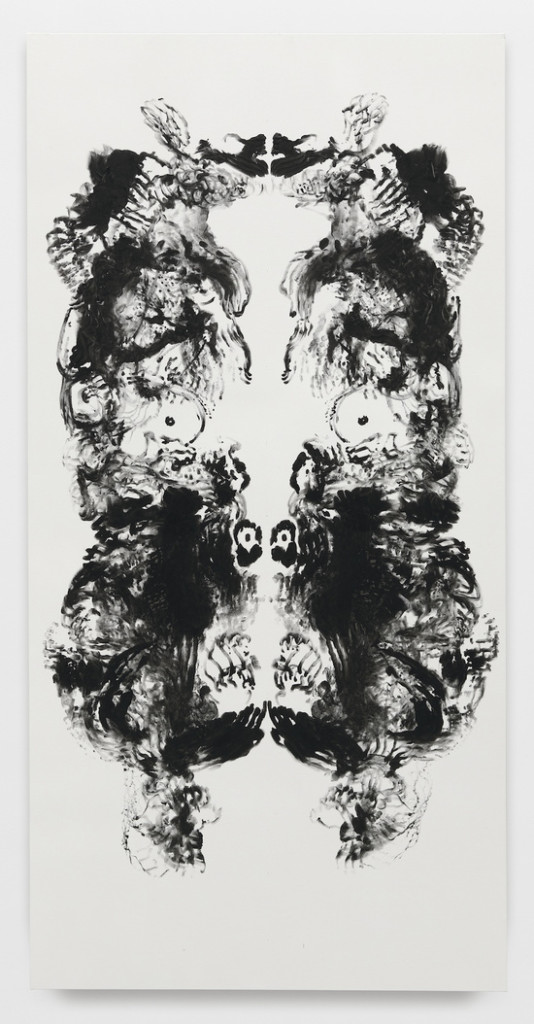

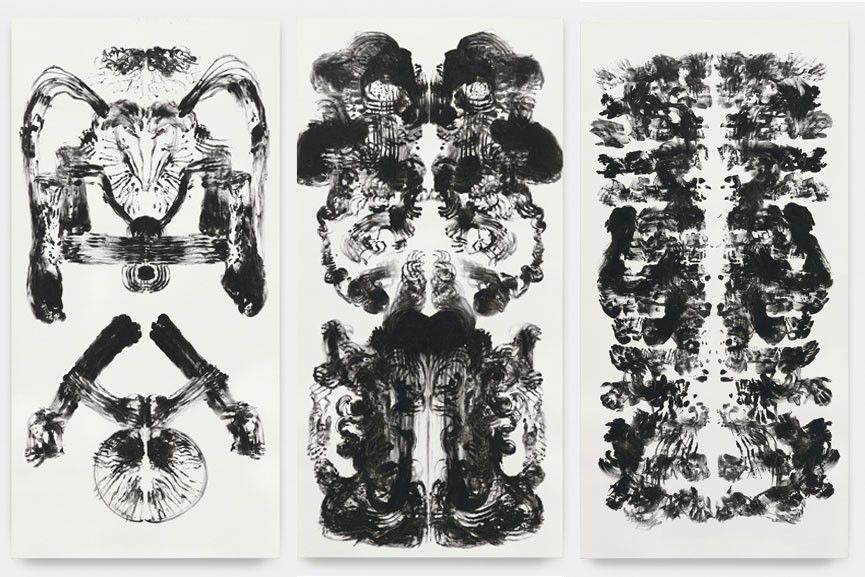

The series possesses the close connection to psychological theory as its name would imply; however, rather than Freud, the paintings channel Rorschach. The immense works are are Wallinger’s own inkblots; each painting a unique abstraction in black and white created with the artist’s own figure. While an antiquated cliche in the field, the psychologist’s inkblots have seen new life and have become a popular composition and subject in art. I most recently experienced them in an atypical series of paintings by American artist Kerry James Marshall. Rorschach and early twentieth century psychology has often been a point of contention for me. The era has been no stranger to salacious inquiry and popular intrigue. If it wasn’t for Wallinger’s ability to reach beyond the myth, as Marshall did, I would be less taken by them. In fact, Wallinger seems unphased by the connection. These paintings are not Rorschach tests, the artist has no particular interest in exploring the subconscious of those who gaze upon them. As with his past work, Wallinger proudly displays himself and allows his viewers to complete the picture.

While Wallinger’s id paintings are subdued pictorially in contrast to early works, free from overt associations with the English aristocracy, they conjure many of the emotions that have become part of his artistic lexicon. You are not left with any doubt that the work is Wallinger’s. Measuring the artist’s wingspan and close to twice his height, you experience a physical affinity to them. The human body is the sole tool in their creation. Their scale is intimidating but equally vulnerable as the soft marks made from a lingering finger upon the canvas. It’s a duality I’ve grown accustomed to in Wallinger’s work. While the bear costume that adorns him in Sleeper may flash its teeth and lurk menacingly, there is a fragile human inside struggling against the fatigue of the prolonged performance. Wallinger’s id paintings portray the same man.

From a compositional perspective, there is much to retrieve from Rorschach’s inkblots. Their strict symmetric design follow a level of formalism and attention to conventional mathematical beauty that they could be considered devotional icons, yet they possess infinite interpretation. Wallinger has a certain fancy for artistic and cultural formalism. Within its clearly defined lines, he is able to interrogate the particulars, the stereotypes, and the absurd. I make comparisons between these paintings and his interest in English equestrian culture in the early 1990s, when Wallinger purchased and trained a racehorse, which he aptly named “A Real Work of Art.” Wallinger readily adopts culture at its most conventional and its most predictably formal, for the purpose of disassembling it and leaving its rudimentary pieces to be negotiated by the viewer.

Despite the significant presence of his id paintings, the dual exhibitions still capture Wallinger’s cheeky, self-aware personality. The artist’s Self Portrait series featured in Edinburgh, as well as Shadow Walker and Mark in Dundee, verge on narcissistic from the surface. A collection of paintings featuring the prominent letter “I” rendered in a selection of digital and manual fonts, an artist filming his own shadow, and inscribing his name on walls and everyday items all seem to point to an painfully vain artist. It is true, these works are about the self, but the subjective self, not the artist’s self. They possess a distance from the tangible body that created them. It is not the artist looking out at the world, but the world looking at itself in them. There is no ownership to the letter “I” nor the shadow on the ground. The viewer is as much the keeper of these images as Wallinger.

The pervasive feelings of subjectivity, absurdity, and contempt that seem rooted in Wallinger’s work make associations to Duchamp commonplace. While I cannot deny that connections can be made between Wallinger and the infamous father of the avant-garde; there is a simplicity to the relationship that sells Wallinger short. Contemporary art loves Duchamp, his attacks on the aristocratic and on the manufactured mind of the art world has informed art making for the last century; but Wallinger isn’t simply repurposing cultural imagery in an attempt to redefine it in another context. He is not holding his nose up to an elitist system, but rather bringing a level of humanism into a sterile environment. His work is about the human form physically, psychologically, and communally, a representation of the self, internally and externally. There is more than a fountain here. Wallinger exhibits himself and welcomes self-examination.

Mark Wallinger: MARK runs at The Fruitmarket Gallery and Dundee Contemporary through June 4, 2017.