Merce Cunningham: Common Time

by Robert Chase Heishman

Two dancers lay on a rich, saturated pink carpet—their duet, at first, appears as an almost imperceptible one. Through continuous, extremely gradual movements, each dancer moves from one position to the next, over the course of what is an hours-long performance piece. The presence of the performers’ bodies, their slowly developing forms, is something akin to the magic of witnessing a latent image emerging onto light-sensitive paper in a darkroom. This is the work of New York-based choreographer Maria Hassabi, entitled STAGING (2017), commissioned by the Walker Art Center to premiere throughout the exhibition Merce Cunningham: Common Time, concurrently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Hassabi’s performance works display a remarkable durational stamina that assists in priming a viewer to slow down and pay attention. And so, I find myself sitting on the carpet to further take my time watching the thawing dancer’s positions. Specific moments of Hassabi’s dance transport me to Cunningham’s 1968 work, RainForest, where the performers enact animalistic movements on the stage floor, as Andy Warhol’s silver Mylar clouds float, hover, and move in cumulus formations. Though we are only at the entrance to the exhibition Common Time, Hassabi’s performance is an appropriate reminder that Cunningham’s legacy is felt most when one is bearing witness to bodies in exploration of new movements.

It goes without saying that Merce Cunningham was a rare choreographer. Historically, there have always been disruptive figures who have been on the vanguard of their own pathway, and, in doing so, invite and influence other artists to join them on their journey—however, the way Cunningham built collaboration into his dances was (and still is) a radical model, one that is curious, open-minded, and always willing to take risks if led to an expansion of possibilities. The concurrent exhibition on view at the Walker and MCA Chicago foreground Cunningham’s artistic collaborations, focusing on his key concept of “common time,” whereby the elements of his performance apparatus (e.g. dance, music, costumes, décor, and lighting) are created independent of one another, but come together as interdependent, kept under the same constraints. It was often during the dress rehearsal that everything merged and was experienced in relation to one another. This collision of artistic forces was indicative of how Cunningham worked: put it all together and see what happens. Or, as John Cage once put it when speaking to how his music accompanied Cunningham’s dances, “Merce does his thing and I do mine, and for your convenience, we put them together.”

My understanding of Cunningham’s oeuvre is not academic, but rather stems from time spent with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) while collaborating as a décor artist for the work Split-Sides (2003). My involvement with the MCDC was the result of chance, curiosity, and serendipity while meeting Trevor Carlson, who was then the Executive Director of the Cunningham Dance Foundation, and a trusted advisor and friend to Cunningham. Alongside him, Carlson played key roles in orchestrating certain collaborations, one being Split-Sides, which I worked on. This was the beginning of my life as an artist, and a member of the Cunningham “family.” For the tail-end of my senior year in high school, and the rest of the year 2003, I traveled to and from New York for production meetings, MCDC performances, and meals at Cunningham’s loft. I can still remember the water stains on the wooden floor near the windows where John Cage once had his plants, and seeing Jasper John’s 0 through 9 (1960) hanging on the wall.

Each trip to New York was a new experience. Days began and ended at Cunningham’s longtime Westbeth studio, effortlessly floating along from one activity to the next, all the while creating photographic décor for the piece. The days teemed with new experiences: one moment Sigur Rós was recording his voice and Cunningham dancers’ feet on the studio floor, the next I was on top of a building assisting fellow collaborator Catherine Yass shoot streaky, long-exposure 4×5 view camera photographs of the surrounding skyscrapers. I was setting up make-shift darkrooms to process the pinhole photos I was making, once in the basement of the MCDC studios, another in Cunningham’s dressing room at Bard College. His philosophy, of trying to say “yes” rather than “no” to experiences, was a vapor all of us collaborators (and staff) gladly inhaled. “Common time” was not so much a concept, but a lived experience.

While the concurrent exhibitions survey Cunningham’s artistic collaborations for the public, I walk through both shows searching for Merce’s movement. From Frank Stella’s décor for Scramble (1967), a series of movable horizontal bands of color in high-keyed primary and tertiary hues, to Cunningham’s own drawings of animals and birds, with their charming illustrative cadence, or the décor and costumes by Robert Rauschenberg for SummerSpace (1958), which carry fields of dotted backdrops and corresponding bodysuits, each piece unfolds as an immensely sonorous experience. So too is seeing the comically headless sweater, designed for Antic Meet (1958), patterned in red and green with an additional arm length for where the neck should be, or an inhabitable version of the Large Glass (originally conceived by Marcel Duchamp, but scaled-up for the stage by Jasper Johns) for the work Walkaround Time (1968). Like memoryobjects, these artifacts consider the legacy of a choreographer, and how that lives on. They were once inhabited, moving—they cannot stand-in or replace the dancer’s movement. As Cunningham stated, “You have to love dancing to stick to it. It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold, nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive.”

With the exception of Cunningham’s “video dance” works created in collaboration with multidisciplinary artist Charles Atlas, the film recordings of his dances, while immensely important and beautiful, cannot replicate the immediate experience of the works as they were in the moment. Without prior primary experiences of seeing the MCDC perform countless times (sometimes in these costumes, against these very sets), the question of how the visual arts narrative might overshadow the performative narrative of Cunningham’s oeuvre begs to be asked. While the thread that weaves the myriad interdisciplinary artifacts on view in both iterations of Common Time is, of course, Cunningham’s dance work, many of the objects within the exhibitions have the remarkable capacity to double as compelling, self-reliant artworks in their own right. This quality is the beauty of the freedom Cunningham gave to each artist, myself included. The works produced for his dances were the fullest version of décor—costumes, music, etc.—that each collaborating artist had to offer. The installations within both exhibitions risk speaking to (and/ or for) the essentially immaterial record of the MCDC performances—even video documentation of a dance, as alive as it may seem, chances a different experience.

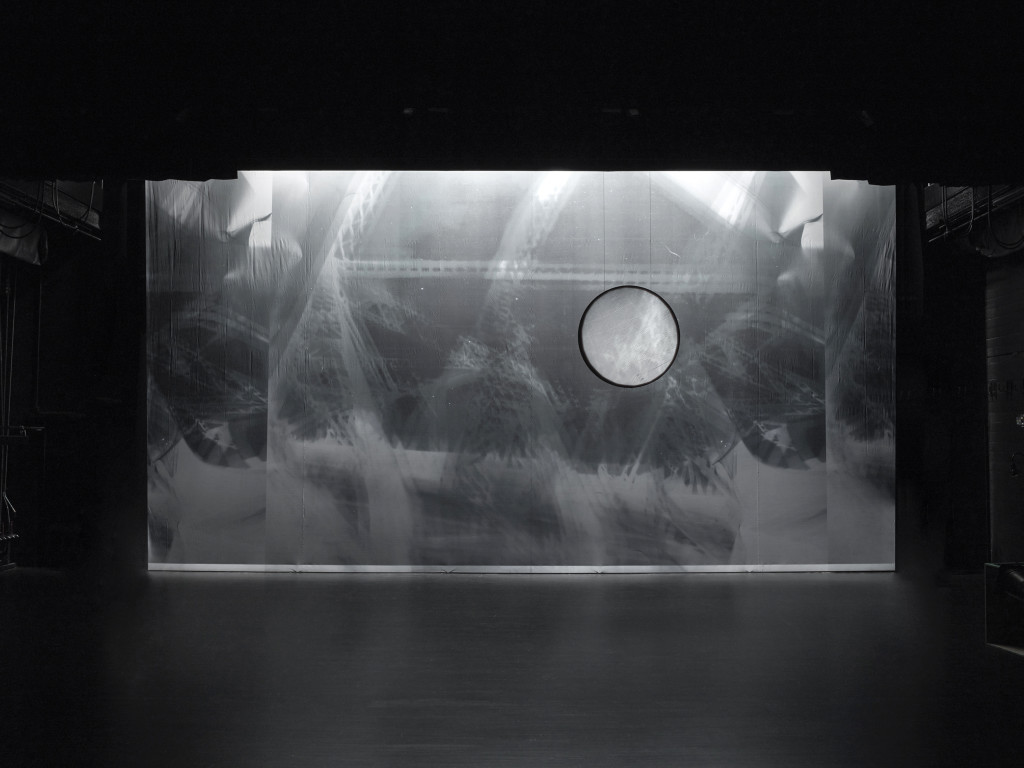

In his 1983 text entitled “Collaborating with Visual Artists,” Cunningham writes, “Stage space and camera space are two different worlds. One is static with the parameters fixed; the other, more limited in size sometimes, but flexible and a situation where the space itself can change. The two spaces function differently for the eye. The stage, as you look at it, goes from wide at the front to narrow in the rear; the camera just the opposite—its rectangular shape narrow at the front and widening out on all four sides moving towards the back of the space.”1 Walking past another one of Hassabi’s dancers performing in front of the large silver mylar moon-shaped décor by Morris Graves from Inlets (1977), the room opens up to a cave of projections. The work by Charles Atlas, entitled MC9 (2012)— Merce Cunningham to the 9th power—is a brilliant tribute to Merce’s life. Countless video documents of MCDC performances, “video dances,” and more off-the-cuff, pedestrian videos (my personal favorite is the video of Merce simply staged with a ballet bar called, Just Dancing) make up this installation. Despite being comprised of reproductions, the work feels completely in line with Cunningham’s Events, which he described as being “comprised of dances from the repertory, or parts of them, as well as movement sequences made particularly for them, are mostly given in non-proscenium spaces.” Perhaps more contemporarily one might describe them as a choreographic version of a “remix.”

Going from seeing Atlas’ installation MC9 to seeing enactments of the Events scheduled during the opening weekend of Common Time at the Walker Art Center is an example of the primacy of the performance—of the importance of being there. Having made the explicit decision to disband his company upon his death, the former Cunningham dancers Dylan Crossman, Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, and Melissa Toogood pierce the room with their movements. Arranged and staged by Andrea Weber, another former MCDC member, there are elements of the Events that even I can recognize—each dancer’s body has a unique presence, something that Merce always aimed to work with, but not necessarily dictate. When Jonah Bokaer left the MCDC to pursue his own choreography, Silas Riener took over his solo for Split-Sides. It was one of the first times I saw how Cunningham adapted his work from one dancer’s body to another—while Bokaer’s version of the Split-Sides solo was performed with dutiful movements, at times so precise they were avatar-esque (this quality is what I love about his dancing), Riener’s body inhabited the solo with remarkable gravity, nuance, and a palpable sense of his interiority as he shifts from one section of movement to the next. In a recent interview, Riener said of the work he did with Cunningham, “I’ve never been so intimately familiar with another artist’s work, […] he feels present to me constantly.”2

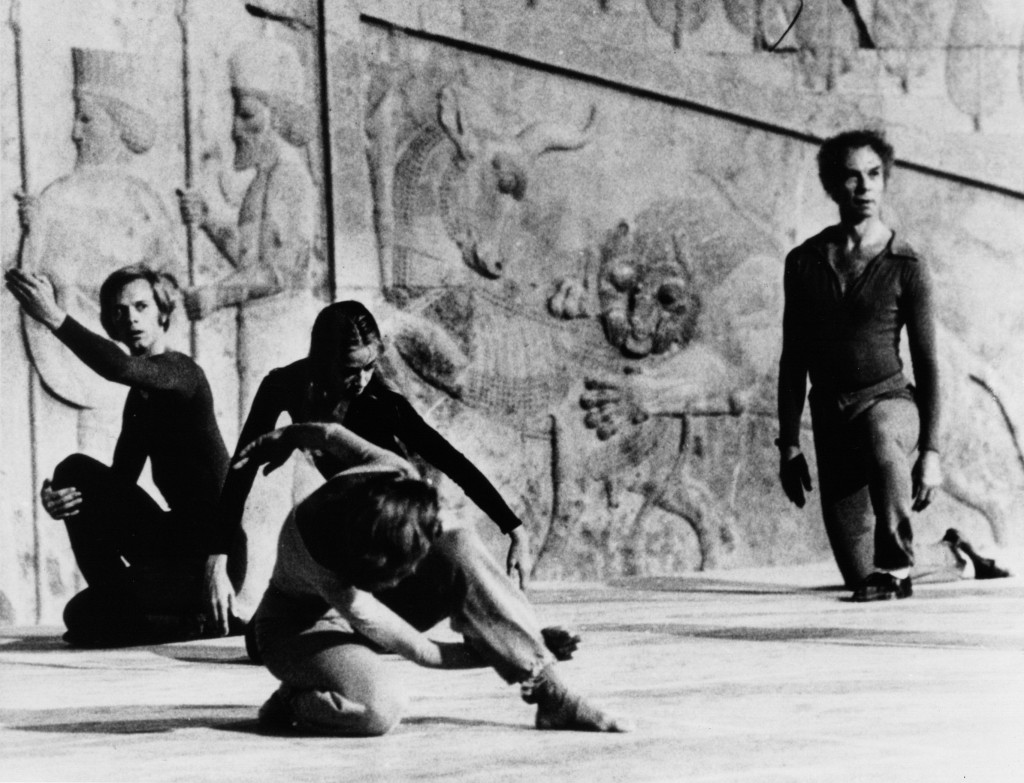

I once accompanied Carlson and Cunningham to New Hampshire, after getting trapped in New York due to an electrical “blackout” that crippled the city’s infrastructure for a full 24 hours—we went by car so that Merce could accept an award at the McDowell Colonies. The visionary vocalist Meredith Monk was there to sing for the occasion, her piece aptly called, ‘M-E-R-C-E.’ It was the first time I had ever heard (and met) Monk—her voice is many things, but mostly power, clarity, and range. At times, it sounded as though she split her voice, and was singing with herself. The song was emblematic of Cunningham’s reach as an artistic figure—the next time I would hear Monk sing was Merce’s memorial at the Park Avenue Armory in 2009. As the evening of countless performances across three stages came to a close, her voice was the only sound in the space. While she sang an excerpt from her 1971 song, Porch, I meditated on the backdrop above her—it resembled Robert Rauschenberg’s Automobile Tire Print (1953), but the many markings were made instead by a skinny tread. I eventually realized the markings were of Merce’s wheelchair tires. They were the marks of a choreographer whose curiosity of movement and dance continued until the very end. As Meredith’s voice fell silent, so did the room. In the silence, I closed my eyes to imagine the entirety of Cunningham’s work I had seen during my work with him. My mind rests on the Warhol Silver Clouds décor from RainForest, and a comment Merce made, that “during an Event in Persepolis in Iran, a number of years back, one pillow floated away into the night sky.”