Mirror Stage: In Conversation with Conor Backman

by Stephanie Cristello

– Originally published on New American Paintings –

We trace history in a similar way we trace source. The significance of certain symbols have a sense of time to them, which is neither part of the object, nor a prescription onto the object – but an affect of belonging, in a condensed perspective, from a certain point in time. This is how a lot of subjects in pre-modern painting history operate. However, how we are able to codify and redact certain elements in this history as belonging to a stylized moment is always overthrown by quotation. Styles are recycled, borrowed, and misplaced within a linear timeline – as if painters were forever throwing the images within the current object they are painting into the cannon of the past by sampling tropes and motifs of another time. Conor Backman is a versatile painter who is able to engage with this cannon, while still existing very much in the present. The sense of time in his paintings belongs to various moments at once, carrying the significance of pre-modern subjects that once operated as symbols, the preoccupation with flatness as a form discovered with modernism, and the post-modern all-over appropriation that works its way into how we deal with mediated space through a different, more contemporary lens of painting. Like most artists whose work I discover, I first accessed Backman’s work online. His work can also be viewed in person in Fruits/Flowers/Appliances, currently on view at LVL3. Below is the record of a series of conversations we had on ideas of flatness, painting as trade, trompe l’oeil, and levels of mediation and reduction in representational painting.

Stephanie Cristello: Citrus is an interesting subject as a motif in the history of painting – an allusion to the still life tradition, but also of exoticism, opulence, and leisure. How do you figure this subject into your work? Is it in reference to a specific history, or does is hinge more on affect?

Conor Backman: Orange is one of those rare words that functions equally as both noun and adjective. I was first drawn to using the orange for this linguistic reason. Orange is both immaterial color, and an object in the round. I have also always liked the gesture of peeling an orange in one piece. I recently rediscovered the ‘orange peel map’, the homolosine projection, and started thinking about the relationship of cartography to representational painting. Both have always dealt with the problem of first translating the round into the flat.

In my last exhibition I reproduced a detail from Van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait, which includes a few oranges on a windowsill. At the time, they would have been a symbol of wealth, and having them in Europe either meant owning a greenhouse, or shipping from the tropics. Today the wealthy are constructing air-conditioned buildings in the tropics, and the previous function of greenhouses is more likely served by Amazon.com. In this sense, the peeled orange also works as a symbol for the globalized, ‘flattened’, world.

SC: With regards to this subject, does the concept of trade influence your practice? Such as the idea of once specialty items such as tea, in green/tree/orange/house/ice/tea/black/box, or in a more general sense, of painting as a type of skilled trade?

CB: I am interested in trade as both practice and exchange. In terms of exchange, I have been thinking more about information exchange, rather than market exchange. For example, I have been making paintings recently that are framed behind grey Plexiglas, as a reference to a process that occurs on a computer screen. This framing device points to the exchange of information that happens between the documentation of the painting and its dissemination, but also limits the possibility of an accurate “on-screen” translation of the painted canvas.

As for the practice of painting as a type of trade, I like to think of my studio as a factory somewhere between shop and home office. Although they sound very similar, I am more interested in the way Winslow Homer used the word factory to describe his studio in rural Maine – as a populist statement of working independent of the machine – than the Warholian pop art model of mass production, artist as machine.

SC: Is an inaccurate translation the point? This is not the same translation of information through technology that Guyton uses, for example. It is more material, less founded on the technological or the machine, and exists as painting first, then image – not the other way around.

CB: The work begins with a digital photograph, which is translated into a painting. I don’t think I necessarily render the image better or worse than a machine, but they are nonetheless different.

The piece comes full circle after it is converted into and circulated as a photograph. The experience of viewing the object on a phone or computer is limited, but also expanded. On video, the automatic white balance adjustment completely eliminates the filtering Plexiglas, and hi-res photo adds detail above the capacity of the eye. When viewing these works in the gallery, one is still looking through a screen, and not necessarily ‘closer’ to the painting. The frame both reduces (mostly the experience of the color) but also enhances the work by evening out the facture more than a glazing technique could.

SC: In your latest solo exhibition, Diorama, at Mixed Greens, you promote a clear affinity for trompe l’oeil, which is very in style in this particular moment, but you also avoid those aesthetic niches. It seems that the bodies of work, through constructed through a similar process, hinge on decidedly different aesthetics and subjects. Is the diversity something you implement as a way to avoid a trend? Or is it something that results out of your working through a type of process?

CB: I’m interested in using trompe l’oeil as a tool to communicate certain ideas, but only when it makes sense for the concept of the piece. How an artwork is made can impede on the content if it is read as the common denominator in a show. Working this way can also mean the production of the work happens slower than ideas are generated, so varying the speed of making in the studio can be important to keep ideas active. Sometimes the paintings are more self-reflexive, and use trompe l’oeil for its art historical content. For example, in my previous show at Nudashank, The Other Real, I made several allusions to the allegory of Zeuxis and Parrhasius’s contest, the classic trompe l’oeil tale of painters suspending disbelief. I’d become interested in the story as an illustration of Lacan’s mirror stage, and wanted to make works that used the myth as material without actually employing trompe l’oeil as the means of production.

In other pieces, trompe l’oeil is used to address questions regarding translation, replication, semiotics, or materiality. In my paintings of drumheads, I wanted to focus on the analogy between the imagery and the support. Both a drum and a painted canvas are essentially a skin stretched over a wooden shell, hit with sticks that record a mark. In these pieces trompe l’oeil is a way to bring the two parts of the analogy as close together as possible visually, without other elements of the painting becoming the focus.

SC: Your paintings could be seen as “actors,” though they are not quite theatrical, or prop-like, but instead have a type of persona that attempts to come very close to the viewer. How do you see the works behaving with the viewer – or rather, how is the viewer implemented within the work?

CB: In the dark Plexiglas paintings, the filter that unifies the color also functions like a black mirror, placing the viewer in the work through a reflection. The image itself sits behind this surface, going in and out of focus as one adjusts to looking at the canvas or the glass. The frame in this piece essentially operates like a veil or a screen, with the image acting like a performer between curtain openings and closings.

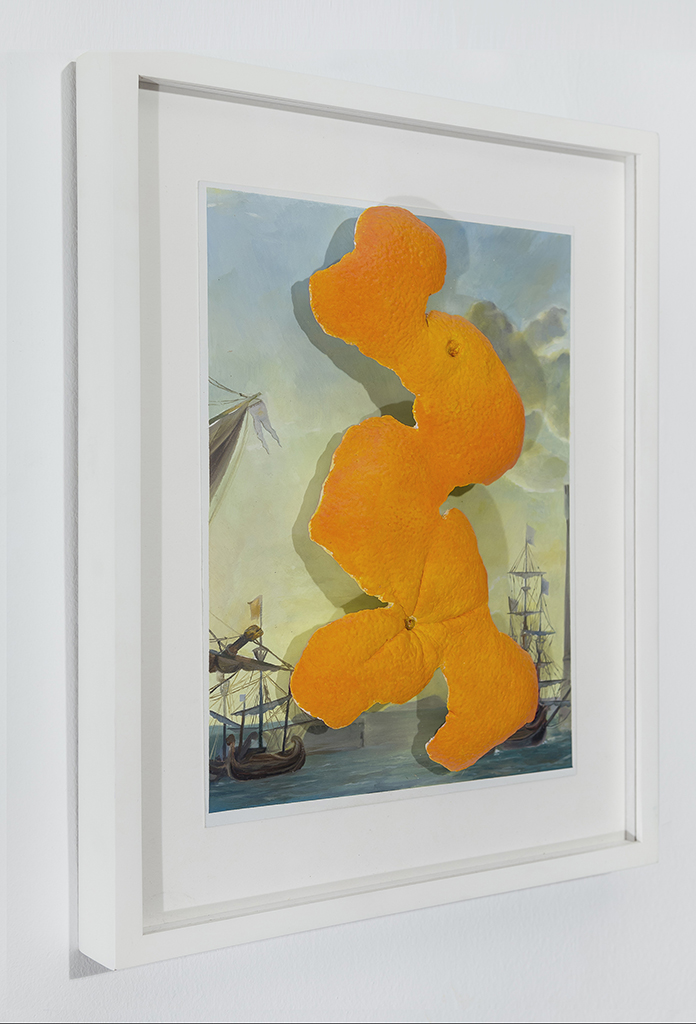

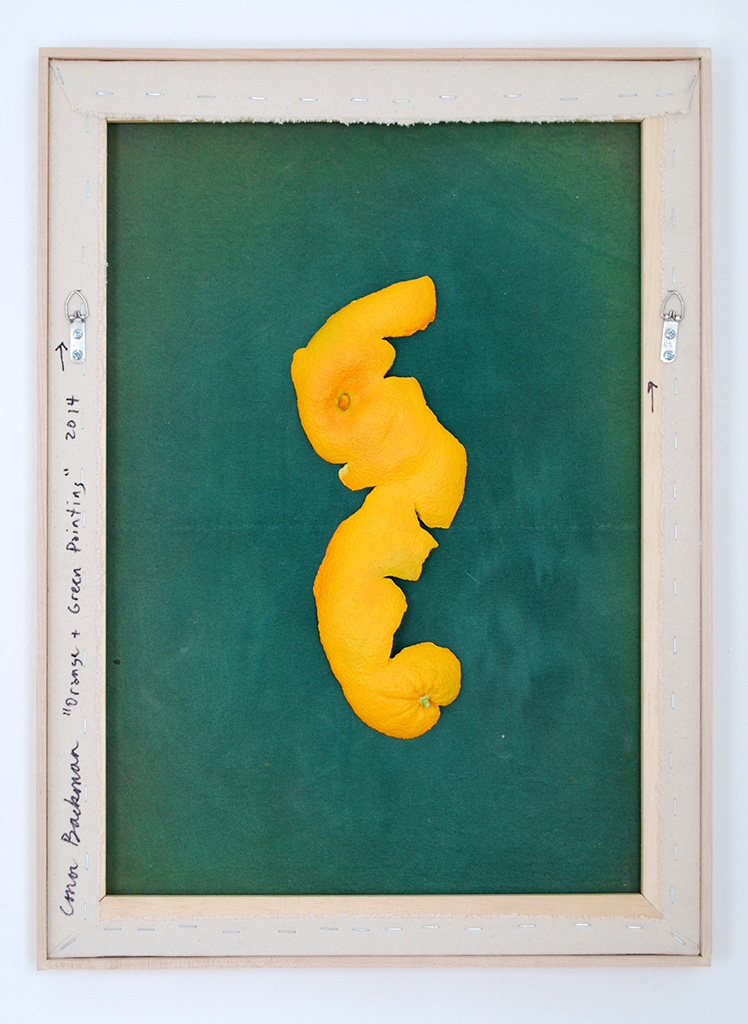

In the other pieces on view at LVL3, I have made casts of flattened orange peels, mounted above the glass on the picture frame. I wanted to push at ideas of painting as a window attempting to bring a viewer into a space, vs. sculpture existing in the same space as the viewer. The oranges are sculptural relief, and also small monochrome paintings. I like the contrast between the monochrome, which is often associated with modernist ideas of flatness, and the sculptural object. The ‘cast’ has a nice connection to acting as well.

SC: Do you see your treatment of flatness as being modern?

CB: If one considers the whole history of painting, it’s interesting to think that most of it was made at a time when the earth was thought to be flat. However, the focus on flatness doesn’t become a primary one until modernism. I’m currently working on a series of paintings in which the stretchers and frames are flipped around so that the back of the canvas with hanging hardware and all faces out from the wall. It references an old trope of trompe l’oeil, but the canvas is stained in a way that is also a stand-in for mid century modernist painting, the kind that is so flat the paint is in the canvas. In these pieces I’m trying to use this idea of flatness as a raw material to be expanded upon.

SC: The way you deal with light in the orangerie and limonaia is much different from your usual paint-to-surface approach, in that the image is flattened and made tonal by the presence of the Plexiglas overlay. In many ways, this move – of referencing a digital type of eliminating brightness, or leveling out of contrast in Photoshop – is just one way that you bring the physical into the digital, and back again. How were you thinking of this piece, and how it deals with the image, with regard to the filter? It seems less about Photoshop, and more about a history of light, but both are present.

CB: I often begin my paintings by projecting a photograph and tracing it onto canvas. At this stage of the work, the canvas acts as a screen, and then I proceed to render the image in paint from photographic sources. Lately, I have been working directly from my laptop. I’ve been interested in the camera obscura and other early proto-filmic devices in relation to this aspect of my process. One of the devices I’ve been reading about recently is the Claude glass, typically a convex black mirror, which was popular in the 19th century among tourists and painters. Tourists used it to enhance their experience of viewing the landscape, the idea being that it made the world look more like a Claude Lorrain painting. Artists used it because it reduced objects onto a flat plane that was easier to translate into painting, much like reference photographs do. The Claude glass also has a clear relationship to Instagram. I often see people tagging photos, particularly landscape photos reminiscent of picturesque or luminist painting, #nofilter, although the camera, or painting, will always be a mediating, reductive, and filtering device.

SC: All representations are mediated; do they necessarily have to be reductive?

CB: A representation does not have to also be reductive. Most of the work associated with ‘reductive art’ is non-representational. In this case I’m thinking about mediation in relation to truth and negation. In terms of the trend of #nofilter on Instagram, I think the negation is the most interesting part. There’s an assertion that an assumed mediation has not been applied. Like the example of the man who asked for coffee without milk and the waiter replied, “sorry, we are out of milk, but can I give you coffee without cream” – or the woman who took a glass of water to bed in case she got thirsty, and an empty glass in case she did not.

Fruits/Flowers/Appliances runs at LVL3 through March 16, 2014.

Conor Backman (b.1988, Arlington, VA) earned BFAs in Sculpture and Painting from VCU in 2011. He currently lives and works in Hudson, NY. He was co-owner of REFERENCE Art Gallery in Richmond, VA, from 2009-2012. He is currently exhibiting work at LVL3, Chicago and Aran Cravey, Los Angeles. He has forthcoming solo exhibitions at James Fuentes, New York and Annarumma, Naples.