At its core, the work of Hank Willis Thomas asks his viewers to observe how mass media constructs the myth of race and identity. In his multi-venue exhibition, currently on view Cleveland, Ohio, is his entire early major series, the 82-part photographs within Unbranded: Reflections in Black Corporate America, 1968–2008, on display within the Cleveland Museum of Art’s photography galleries. The self-titled exhibition, which opened in October of last year, was recently joined in mid-December by the collaborative 5-screen video installation occupying the majority of the Transformer Station, in Question Bridge: Black Males, by Thomas, Chris Johnson, Bayete Ross Smith, and Kamal Sinclair. This project was created to abolish monolithic notions of black male identity, depicting instead a more nuanced and multi-faceted whole image and narrative to the conception of black males. It is a multi-platform project comprised of an interactive website and online learning community, a curriculum for high schools and universities and community events partnered with organizations, centered around debunking the hegemonic identity container of what a “Black” “Male” in America signifies. In an adjoining gallery, selections from Thomas’ current series, Branded, are on view; a critique of the hyper-masculine tropes cycled through capitalist systems – images of NBA players used as figures that equate the exchange and labor of black bodies in major league sports, a type of “modern slavery.” In addition to these series, the exhibition includes a traveling component, Search of the Truth (Truth Booth), a mobile project that features an inflatable cartoon speech bubble with the word TRUTH inscribed on the side. Viewers are invited to enter the booth built into the bubble and complete the statement; “The truth is…,” before a video camera.1 Through these responses, Thomas reveals the invisible corporate power structures that generalize ones experience of embodying any identity; a proposition that our choice to internally identify in a particular manner is one that is constantly in flux. What the piece creates is, instead, a safe space for the viewer to witness and author their own relations – of race, or otherwise – in which the resulting videos can be experienced on the project’s website.

The combined exhibition is the artist’s largest museum survey to date.

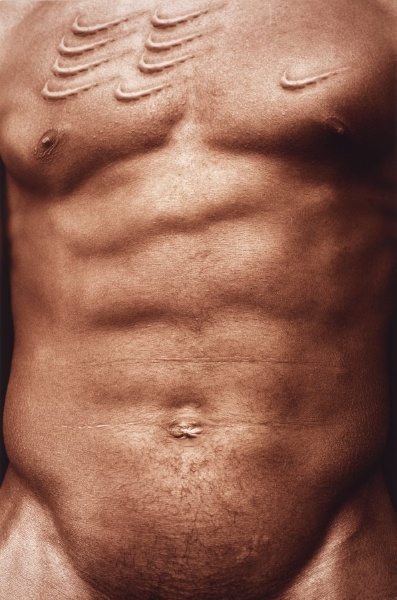

The exhibition relies heavily on the use of advertisement imagery as a platform. In works such as Scarred Chest, from the Branded series, an image of a sexualized black male body is presented to the viewer with multiple raised skin marks in the form of the Nike logo. According to Thomas, this correlates to the slave trade, in which black bodies were scarred with their master’s initials to identify who they belonged to, a signifier utilized in the work to imply that black bodies are now owned by sports, major leagues, and especially NCAA, exploit and “own” the athletes. In the work, Your Skin Has the Power to Protect You, bended knees in a variation of skin tones are presented to the viewer, sourced from what seems like a lotion commercial – yet, it is not the actual product that is being advertised, but rather its effect. That being, what it can produce on the bodies with different melanin compositions, implying that the lighter you are, the greater the ability your skin ha to protect, and its inverse. The manipulated identities of the subjects are often presented as seemingly objective; a concertized formation within the work that is deconstructed in photography and film throughout the exhibition. In Unbranded, Thomas removes all branding information, including logos and text, staging a détournement that investigates the ubiquitous language of advertising through material representations featured in Ebony, Times, Sports Illustrated, and Playboy magazine. The selection for this series is influenced by images from the Civil Rights movement, around 1968–2008, featuring 2 images from each year. This series functions not only as a visual guide to that history, but also depicts the shifting attitudes towards race and gender in corporate America. With regards to representations of African American identity, there are countless mediums in which social and racial identity manifest, and are documented – yet, Thomas presents a steady loyalty to the form of the advertisement. “Many of Thomas’ works, even if they do not appropriate actual ads, employ the same tropes and techniques that make advertising so seductive and successful,” notes Dr. Barbara Tannenbaum, curator of Photography for the CMA. But how are we to interact with this exhibition of still visuals differently in person now, as a culture immersed in the moving image of advertisements (iPhone apps, Tumblr, Instagram, etc.)?

The importance of the photograph, the use of scale and type of prints, such as lenticular, permeates the material read on each of the works – an ethos that is reflected in the understanding of these images as an object. In a text by Jessie Daniels published on Racism Review, she quotes Thomas, “I believe that in part, advertising’s success rests on its ability to reinforce generalizations about race, gender, and ethnicity which can be entertaining, sometimes true, and sometimes horrifying, but which at a core level are a reflection of the way a culture views itself or its aspirations.”2 This sentiment is echoed by Tannenbaum, “The mechanisms by which advertising and the media define identity and manipulate viewers are universal throughout the industrialized world…[Thomas] employs it to address issues that impact us all, such as diversity and tolerance within, as well as between, racial and ethnic groups, and the freedom to determine one’s own fate and to construct one’s own identity.”3 Yet, Thomas’ work is particularly American. With regards to race and gender, it speaks to the African American experience that avoids the association with “elsewhere” – an ever-present attempt to expose this myth of identity perpetuated by a commercial industry.

Thomas’ focus on African American masculinity, in particular, is a call to attention of experience, mentioned explicitly by scholar bell hooks [sic] in her book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, “Whether in an actual prison or not, practically every black male in the United States has been forced to some point in his life hold back the self he wants to express, to repress and contain for fear of being attacked, slaughtered and destroyed.”4 Thomas’ work unmasks the constructed barriers that attempt to constrict manifold identities through presenting the mask itself – a motive that potentially contributes to this history, as it undoes it.

Hank Willis Thomas at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Transformer Station runs through March 9, 2014.

- Litt, Steven. “Comments Hank Willis Thomas at Transformer Station and the Cleveland Museum of Art: Exploring Race, Corporate Power and Cultural Stereotypes.” Cleveland.com. © 2013 Northeast Ohio Media Group LLC., 23 Jan. 2014. Web. 14 Feb. 2014. http://www.cleveland.com/arts/index.ssf/2014/01/hank_willis_thomas_at_the_clev.html.

- Daniels, Jessie. “Hank Willis Thomas: Artist Exploring Commodification of Black Bodies — Racismreview.com.” Racismreviewcom. Racism Review: WordPress, n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2014. http://www.racismreview .com/blog/2010/05/30/hank-willis-thomas-artist/.

- Interview conducted by THE SEEN, February, 2014.

- hooks, bell. We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.http://www.feminish.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/We-Real-Cool-Black-Men-Masculinity2.pdf