Profile of the Curator: Domenico Quaranta

by Dominique Moulon

Domenico Quaranta is a contemporary art critic and curator specialized in new media. He writes regularly for Flash Art and is the author of the book Media, New Media, Postmedia. Living and working in Italy, he teaches Net Art at the Accademia di Brera in Milan.

Dominique Moulon: Is there an artwork or exhibition, or specific book or art center, that you feel best marked the historical emergence of digital media into the art world?

Domenico Quaranta: I don’t think this emergence really happened alone. And probably each of these historical events that happened made something for it and something against it. The ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe in Germany organizes really good exhibitions and presents an integrated collection of media art into contemporary art. As for a book, maybe in the long term it could be Edward A. Shanken’s Art and Electronic Media, published by Phaidon in 2009. That book is pretty clever because it doesn’t approach new media art as a separate field, but instead tries to address the use of new technologies involved in the contemporary art world and the new media art world at large, both as a tool and as a field of research. So you have artists such as Mario Merz together with other artists working on technology in a different way, and also because of the publishing house, Phaidon, it has good chances of having an impact, regardless of the separations between media.

DM: Since video has been widely accepted in contemporary art exhibitions, video art seems to have become a new trend of the past. Do you think this integration is what is currently happening in the realm of digital art?

DQ: For me, new media art or digital art is already in the “past”. Sometimes we’Il keep using the term because it is useful, but it is also dangerous for artists working in this field. Considering Evan Roth’s exhibition View in a Room at XPO gallery in Paris, some works are digital, some works are new media, but many of them are actually totally analogue works. I think many artists really enjoy doing art free from being tied to the medium-based definition – to move in between different things, to be free to use any kind of medium they want.

DM: Often, new media artworks make their way into museum exhibitions and collections through the Design department, as is the case with MoMA, thanks to Paola Antonelli. What do you think of this “backdoor” strategy?

DQ: I was reading an interview with Paola Antonelli yesterday on the train, about the integration of video games in the collection of MoMA. When it happened, I also thought, how it was not a recognition of video games as contemporary art – because it was totally happening through the design department, and within that design-specific context. But in the interview, she said something interesting about this; she basically said that in museums like MoMA, you have to have distinctions between different areas and curators for each field, because it would be difficult to manage it otherwise. The important thing is that the works are entering the collection. When the artists are in the collection of the museum, it almost doesn’t matter if it’s the design department, or the photography department, or the media department. I think that’s a good point. It doesn’t tell that much about the art.

DM: Would you say that there are basically two trends in new media art: one that follows the history of art and another that is more socially oriented?

DQ: This is actually one of the reasons why I don’t think that the media art label makes any sense anymore. We group together things just because they are based on the use of computers, but actually the way the computer entered the art world as a medium today was so variegated and distributed that it can be used for anything. So it’s completely natural to me that artists are using digital and new media with completely different approaches. Some of them are researching into the medium, others are just using it as a tool – talking about it and taking it as a subject – but sometimes they implement the computer without approaching it as a medium at all. So any trend in contemporary art can have an application and development in new media, in a way.

DM: We all use digital tools and services. Would you say that digital artists are the ones who re-appropriate these same technologies and media?

DQ: Definitely. Many of them have adopted that approach, which I think is an interesting one, because it means criticizing and creating an awareness around the things that are simply entering our own lives, without thinking about it, without any adaptation to it. When smartphones came out, and everybody started buying them, we were probably not aware that this was going to affect our lives in such a huge way. It was a complete revolution compared to the user of the computer and the availability of the Internet in the former decade, and now, we have access to the Internet anytime, anywhere, etc, and this has completely changed our social life, our economics, and so on. Artists are entering this dialogue with new technologies with a critical approach, also because they want to make us more aware of the environment we live in.

DM: Your 2008-09 thesis paper was titled War of the Worlds in reference to the conflicted relationship between new media art and contemporary art. Five years later, are we still at war?

DQ: I still see a lot of conflict, yes. Maybe not between the two communities as a whole, but between different perspectives, different views. Also, when you speak about involving artists who have a gallery in your fair [Showoff], and having difficulties integrating them into aspects of the fair, when they are already working with a gallery, because you can almost bypass the gallery. This is a small friction that comes from the fact that you are not playing according to the rules of the contemporary art world, strictly speaking, since new media art has different boundaries.

DM: Would you say that the Internet, which has had a significant impact on consumer habits, is also radically changing our relationship with art, artworks and their uniqueness?

DQ: One of the things that is affecting our relationship with art the most is the fact that we have gotten used to documentation – to seeing art through documentation more than through the actual experience of the object itself. It is very possible that we are visiting the same number of exhibitions that we were visiting before the Internet, but our mediated experience of art has exploded, because before it was just through books and magazines, and now 90% of our experience of what we are exposed to in art is through the Internet.

DM: Is the emergence of artists of the so-called “post-digital” generation, such as Petra Cortright, a sign of the art world’s acceptance of new media?

DQ: Petra is a good example of an artist who uses the Internet as a tool and as a medium for her own work, but at the same time, from a technical point of view, most of her work is, how can I say, really simple… an evolution of video art in an art context that has the Internet as a medium to deliver video art. She has become successful, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that new media art will be accepted in the art world because artists like Petra Cortright are accepted. This is more or less the same with other artists who are playing the game of contemporary art quite well. Because usually, when they become successful, they are in a way labeled as contemporary art, not as strictly new media art – which seem to be synonymous, but have different connotations.

![Petra Cortright, winterlakecomentbounds_ber_nopolesCS5lol2[1], 2012, Steve Turner Gallery, Los Angeles, collection of Hampus Lindwall.](https://theseenjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/04.jpg)

DM: Once the new media art market comes of age, what do you think the role will become of currently dedicated digital art labs and organizations?

DQ: I don’t think this community of new media institutions and nonprofit organizations and so on would or should disappear, because they able to produce experimentation and things that can’t depend on being accepted by the market. One of the reasons why I don’t like addressing new media art as a whole is that I think this term, this definition is still very well suited to things that imply research on the medium, that imply the using of high technologies, and so on. When you are doing art with a phone a computer or the Internet, you are playing your game in a completely different field, in a different world. But high technologies still exist; there are still many technologies and many tools that artists can’t access without entering a laboratory and entering a research department in a university and so on.

DM: If you had to exhibit only one artwork that would represent new media art, which one would it be?

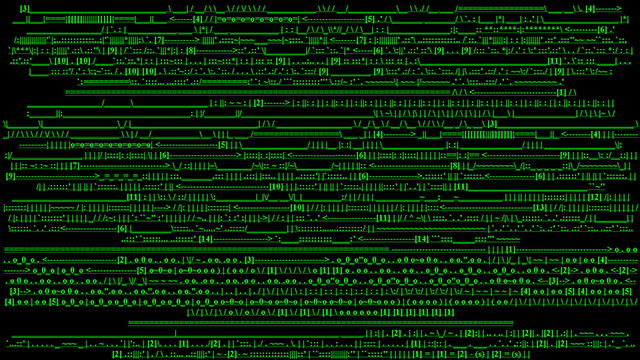

DQ: I would choose Jodi, jodi.org as a whole, as a complete body of work—everything that was posted on jodi.org over the last 20 years would be the subject of the exhibition. The reason, of course, is that Jodi appeared in this critical moment in the history of new media art when consumer technologies appeared and allowed artists to make different work from what was done in the former decades from the 1960s and the ’80s. If now we are talking about the relationship between the two communities, and the presence of new media art in the art world and in the art market, it’s also because at some point, around the ’90s, it became possible to operate with new technologies in a completely different way from what was possible, for example, in the ’80s. And I think that Jodi is a good example of this.

Interview by Dominique Moulon for digitalmcd.com and translated by Valérie Vivancos.