Profile of the Curator: Loreta Lamargese // Part I

by Catherine Lamoureux

Our contemporary susceptibility to distraction paired with the over-stimulating nature of technology has shaped a new relationship to information and to how we absorb, share and aestheticize it. Information consumption now occurs through ubiquitous media that allow news, entertainment and interpersonal communication to coexist and to become increasingly indistinct from one another. I sat down with Loreta Lamargese who curated the exhibition You Won’t Believe (…) which just recently closed at Division Gallery in Montreal to talk about the show and discuss the role of entertainment as a vehicle for information and its place in contemporary art.

Catherine Lamoureux: Tell me about the write up for the exhibition. You speak about entertainment, which I didn’t quite understand at first, but it makes a lot of sense in the context of how we consume art and images at this point in time.

Loreta Lamargese: One important thing that happened for me while putting together this exhibition was that I was referred to a show that was put on at the Walker Art Center in 2000 called Let’s Entertain—it was also thematized around entertainment. I thought it was interesting because in a bit more than a decade, things have changed dramatically in terms of how entertainment functions and what artists are looking at as sources of entertainment. This current show definitely features a younger generation of artists, but everyone in the exhibition is under 42. Entertainment was important to me because I wanted to deal with pleasure, and I ended up using that show as kind of starting point and a lens to look at how things have changed.

CL: I’m guessing the Internet wasn’t referenced as much in that exhibition.

LL: Yeah, although I think the show definitely made reference to the use of networks. It also dealt with entertainment through the notion that it was no longer a distraction. Distraction is always present; to pay attention, we have to be distracted by something else. So first of all, that undercuts the idea of distraction, but it also undercuts the idea of entertainment as distraction. That refers back to Guy Debord and his idea of the spectacle and to how already in the 1960s people were talking about entertainment as being ubiquitous.

CL: Maybe now the lines are much more blurred between our distractions, our entertainment and our sources of information—between pure entertainment and our quotidian consumption of artwork.

LL: There’s also, in terms of art, a turn towards affect theory. A lot of people are talking about theorizing art within that frame, and affect theory is about pleasure principles. This is referred to in the entertainment industry as a way of aestheticizing things, and in the way that people are constantly vying for our attention in order to make everything aesthetic. There are so many ways of looking at the idea of entertainment, its so multifarious, but since I was bringing twenty two artists together I thought why not umbrella them under something that could take so many forms.

CL: It’s fitting that the exhibition website explicitly mimics a buzzfeed page, which is such a huge contemporary source of entertainment, and that the links embedded in the gallery’s address on the site reflect something like your own curation of pleasure, or places on internet we go to fulfill a need to be instantaneously entertained, like Kim Kardashian’s instagram or pictures of dogs.

LL: Well the idea of using Buzzfeed for me, in the most simplistic way, was to adopt this model of aestheticizing information, where the text is always interspersed with gifs or images so that we’re never just consuming textual information, it’s always being put forth through so many aesthetic sources, always connected to a bigger network. In terms of linking to different sources, it was almost an automatic response, thinking about the notion of search history and the fear of it. Network aesthetics really played into this in a huge way.

CL: How do you think network aesthetics come through in the works featured?

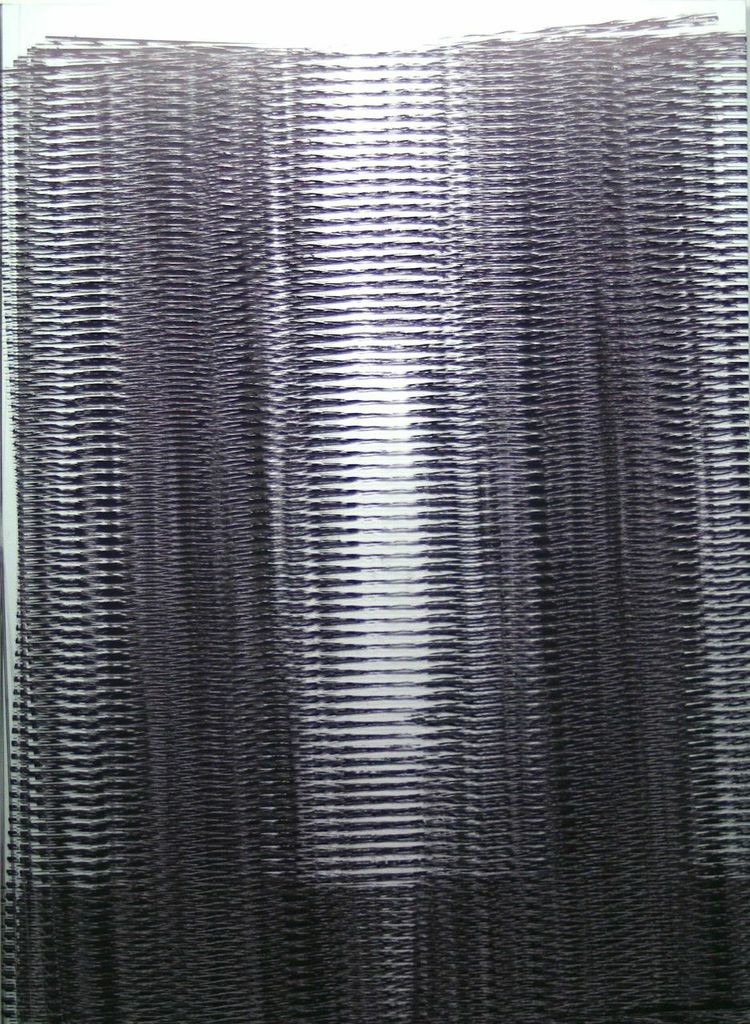

LL: After the main foyer, the first piece you see is probably Jillian Mayer’s My Phone Died Meet Me Here. Seeing as it’s a photograph of this in-situ site-specific mural that exists physically in Miami and it references a kind of punctum for people to come to this place, and that the the image started circulating on Instagram as a part of a network, and that now it exists here, referring to these different places, already this piece establishes this aesthetic model. The works grouped in the second room also belong to this mode of rendering information aesthetic, where elements belonging to the commercial industry, the entertainment industry, and the advertising industry are present, and which are then subverted. You have glitch work, for example Travess Smalley’s piece, which represents all the steps needed to make a billboard without having the actual image inside of it. Or Erika Ceruzzi’s vinyl pieces which are corporate logos that have been glitched, essentially. So there are all these elements that belong to consumptive networks, and these works can be seen as a kind of critique. The term I used with Erika’s pieces is Naomi Klein’s idea of culture jamming, and this recurs throughout the exhibition.

CL: The notion of critiquing consumerism through humor comes out in a lot of the pieces, and I think that’s interesting in relation to the consumption of information and images you addressed earlier.

LL: I think humor became important to me in a lot of different ways. When we’re looking to be entertained, of course there’s an element of humor involved and comedy comes into play, because thats just the most basal way of being entertained, really. So a lot of the works have this element of comedy that is inextricable from the work. A lot of the artists toy with this a lot, like Chloe Wise or Jayson Musson, and there are other works that aren’t blatantly comedic though humor is a part of the mechanisms of it, like Matt Goerzen’s work for example.

CL: And a lot of them are also fairly political.

LL: Yeah, I think that some of the critique that’s happening in a lot of the work functions by using the codes of different systems that the artists are aiming to critique, and by employing them and making them strange. So a kind of campiness happens a lot, or a masquerading, so they’re critiquing from within. That has such a history behind it, but I like the idea of the carnival that’s behind this, of carnivalizing.

CL: So much of the work is really loud.

LL: That’s important because they’re kind of competing with one another, just as when we’re looking to be entertained by different sources. The works do a really similar thing.

Loreta Lamargese is a curator and art historian based in Montreal. She holds a master’s degree with a focus in art history from the University of Chicago and an honours bachelor’s degree in art history from McGill University.