Psychotic Images: The Surrealist Scientific Films of Éric Duvivier

by Jade Barget

The eye exists in an untamed state. It presides over the conventional exchange of signals apparently required by the navigation of the mind. But who will draw up the scale of vision? There exists what I have seen many times […] There exists also what I am beginning to see that is not visible.1—André Breton

How to Present the Mind’s Bending?

Throughout the 1960s, the Sandoz Laboratory, known for synthesizing LSD in 1938, commissioned works of experimental cinema in order to foster a new understanding of psychiatry. This endeavor, which aimed to create avenues of investigation into psychological states, was independent from the medical discourse and specialist expertise of the time. The body of work that was amassed over this period was gathered in the now-defunct Cinématèque Sandoz. Amongst the filmmakers working with the laboratory was Éric Duvivier (1928–2018), a French filmmaker who developed a new cinematic genre: the Surrealist scientific film.

Surrealism, a cultural movement rising in the aftermath of WWI, set out to explore the unconscious mind through visual imagery. When creating films which examined psychological and psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, depression, or psychosis, Duvivier employed Surrealist methodologies and experiments.2

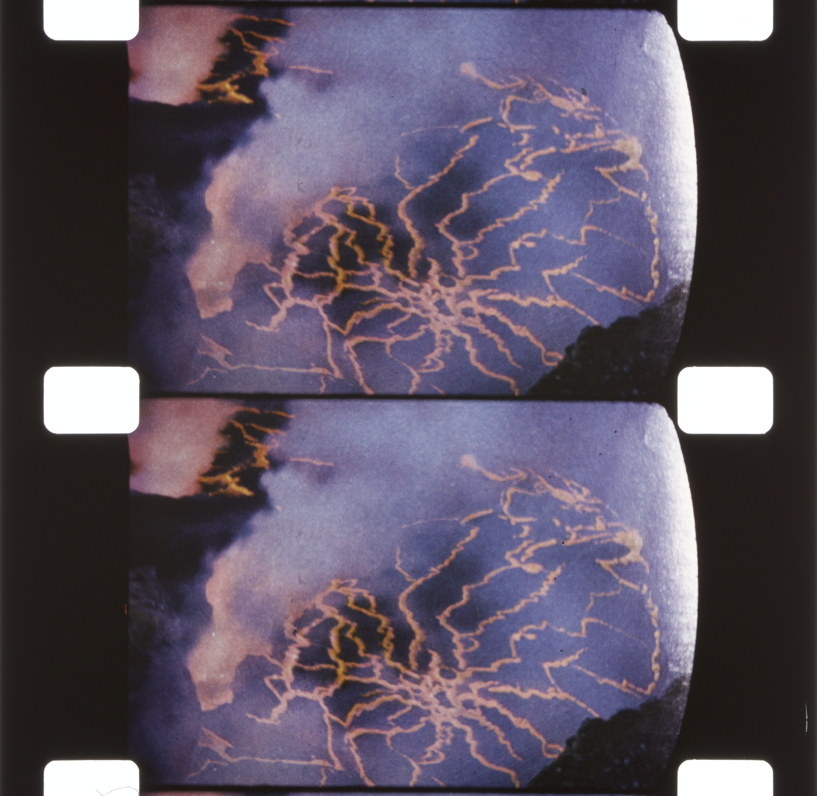

Whilst Duvivier’s catalogue of work, which included hundreds of short conceptual medical films, generally circulated between specialist audiences at professional conferences, a few films broke away from medical circles to reach avant garde audiences of the 1960s. One such film, Images du monde visionnaire [Images from the Visionary World] (1963), a collaboration with poet Henri Michaux (1899–1984), was inspired by his writings.3 The short film—part of Duvivier’s Hallucinations series, a Sandoz-funded research project aimed at understanding the relationship between the effects of psychoactive drug and psychosis—delves into his experiences with Mescaline. Three other films are part of the series: La perception et l’imaginaire [Perception and the Imaginary] (1964), an exploration of altering perception through different methods such as sensorial isolation, hallucinogenic drugs intake, or exposure to light; Concerto méchanique pour la folie [Mechanical Concerto for Madness] (1963), drawing links between mental health and the automation of the world; and La femme à 100 têtes [The Hundred Headed Woman] (1967), an investigation into the Surrealist collages of Max Ernst that explores the mind’s ability to find patterns and meanings in chaos.

The Images Will Be Insufficient

Michaux considers Images du monde visionnaire a failure; announced in the opening of the film in a voice-over disclaimer, the narration states:

When it was proposed to make a film about Mescaline hallucinations, I have declared, I have repeated and I repeat it again, that it is to attempt the impossible. Even in a superior film, made with substantial means with all one needs for an exceptional production, I must state beforehand that the images will be insufficient. They would have to be more dazzling, more unstable, more subtle, more changeable, more ungraspable, more trembling, more tormenting, more writhing, infinitely more charged, more intensely beautiful, more frighteningly colored, more aggressive, more idiotic, more strange. With regard to the film’s speed, it should be so high that all scenes would have to fit in fifty seconds.4

Despite this announcement, the film begins. Michaux deems the film just sufficient enough to show those interested in vision how the Mescaline experience differs from dreams, and how it might, in some cases, resemble the experiences described by patients suffering from psychosis. At its best, the film bears witness to something that surpasses thought and cannot be represented. Michaux’s introductory disclaimer challenges the viewer to imagine more than what the images give away. As André Breton writes, it is an invitation to begin to see that which exists but is not visible.

This concern with that which exceeds representation is a leitmotif in Duvivier’s Surrealist medical films. In Monde du schizophrene [The World of the Schizophrenic] (1961) a voice-over asks:

“Comment faire comprendre, sentir, cette lente dissolution de l’être?,” how can one understand and feel the slow dissolution of the self?5

What is the distance between images and events that makes some experiences unrepresentable? For Michaux, images are insufficient representations of that which exceeds thought. Jacques Rancière prefers speaking of an excess.6 In place of declaring the sheer impossibility of representing certain events, Rancière delves into the notion of irrepresentability, locating an excess of representation within the very nature of images; images render too visible, too intelligible. There is too much knowledge.

To suggest the unrepresentable, there needs to be a balance between the seen and the unseen, the known and the unknown. Michaux’s writings on hallucinatory states, for instance, invoke images but do not finalize them. In Images du monde visionnaire, the written word works within the quasi-visible, manifesting what remains unseen; there is an absence, an obscurity, which nourishes the unfathomable. Words do not allow us to see; they allow us to begin seeing.

Images of Madness and the Madness of Images

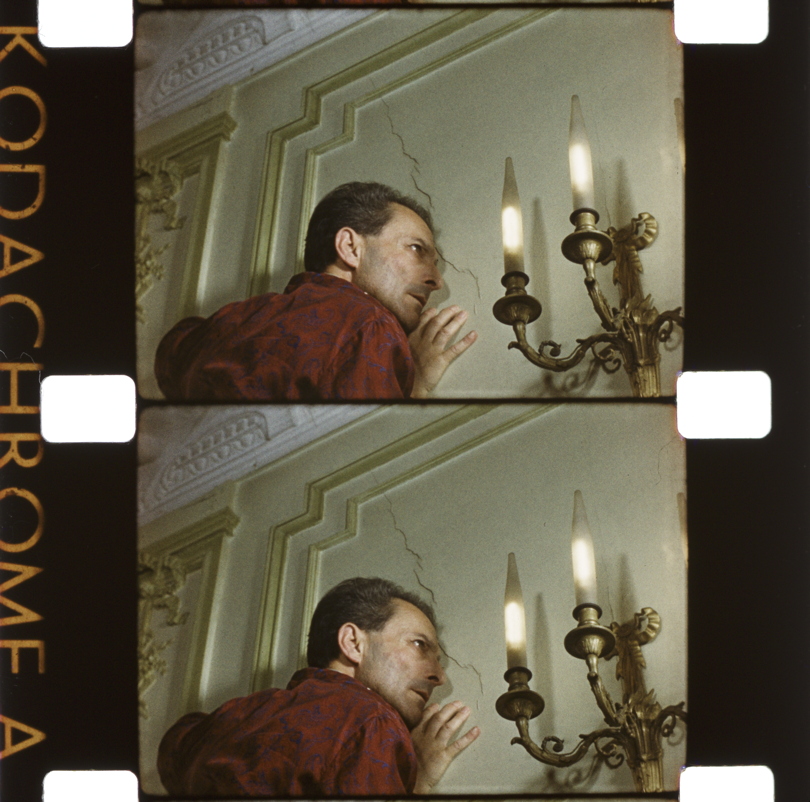

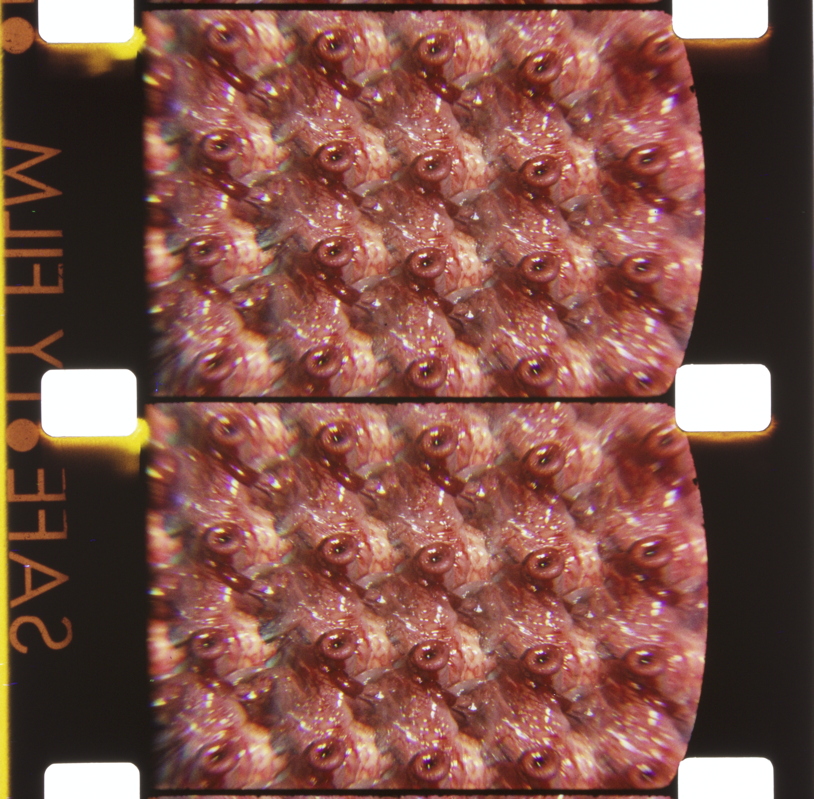

How can we, as viewers, understand and feel the slow dissolution of self? In Duvivier’s strange archive of digitized medical films, outdated and undead, frenetically oscillating between visual art and psychiatry, it is as if the images themselves have become psychoactive.

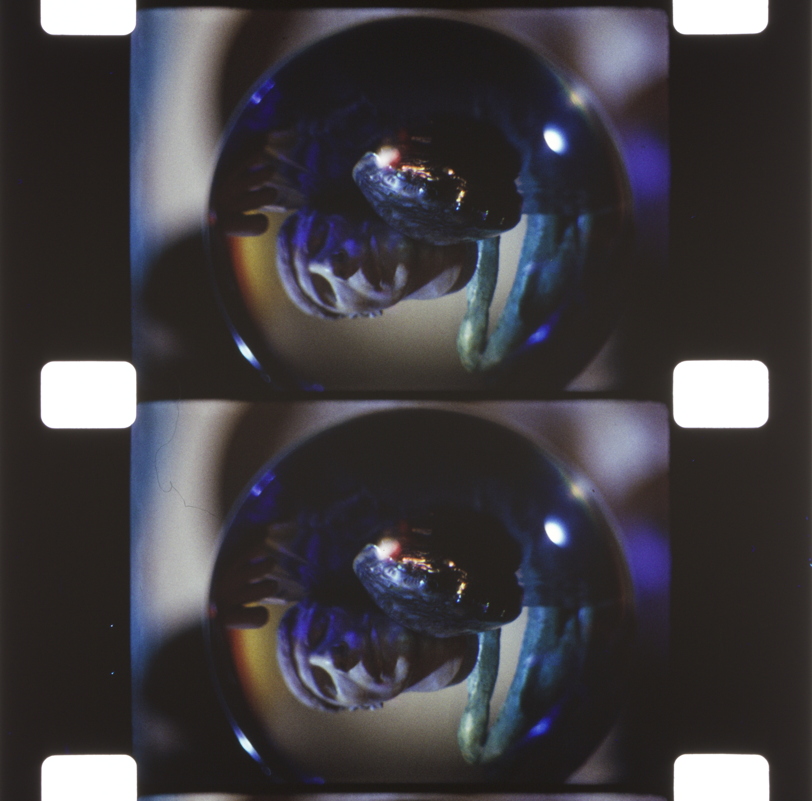

In La perception et l’imaginaire, Duvivier explores processes that alter perception, including the Rorschach test, which analyzes what one sees in abstract content such as coffee stains. The film shows a plate with residue, an abstract image with lights, a crystal ball—the viewer begins to both see and unsee.

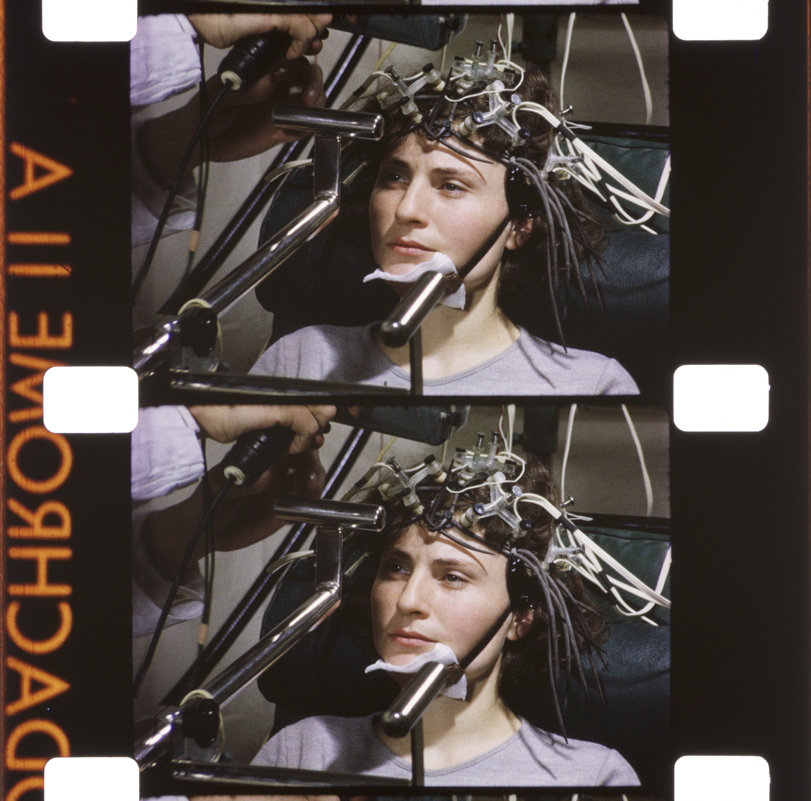

In another experiment, the film records patients sharing hallucinations they have experienced by repetitive, bright light projections. The voice-over in the film speaks of post-images:visual aftereffects that linger in the viewer’s field of vision once the experiments have ended. This intangible residue, or post-images, constantly excite and disappoint. We witness the inescapable madness of our own mind.

Duvivier’s choice of images, extracted and collaged from art history and medical footage, point to elements that lie between the visible and invisible, between the said and the unsaid. These images are never static, always fading and decaying. Almost discernible, their ambiguity pulls the attention of the struggling viewer towards something which is not there. It is a lack of coherence that produces a space for psychosis: we begin to see images which have never really existed.

- André Breton, ‘Le Surréalisme et la peinture’ first published in La Révolution surrealiste, no. 4 (15 July 1925), pp. 25–30, as quoted by J.H. Matthews, Surrealism and Film (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1971), p.12.

- Most of Duvivier’s films are available to watch on Canal-U, a French audio-visual library for academic research.

- Henri Michaux, Misérable Miracle, (Monaco: Editions du Rocher, 1956).

- Images du monde visionnaire (1964), Henri Michaux and Eric Duvivier, [accessed February 19, 2021].

- Author’s translation.

- Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image, ‘Are Some Things Unrepresentable?’, (London, New York: Verso Books, 2019), p. 109–138.