Because We Were Queers: Queer British Art 1861-1967

by Stephen F. Eisenman

One reason “queer” has gained ground over “gay” and “lesbian” is that everybody can claim it and nobody has to pay for it. To be gay is to occupy a distinct social space and risk ostracism. To be queer however, is simply to assert difference, and who doesn’t want that? I was recently at a family dinner where a tall, lean, university student from Manchester gently chided his host for using the term gay and not queer. “Queer means you don’t accept artificial divisions between people, and you’re free to be who you are. Me and my mates,” he added, “think of ourselves as queer.” His girlfriend nodded agreement.

Veterans of the gay liberation movement may feel that queers want to have their cake and eat it, but there is an undoubted advantage to the new formulation. It encourages broader alliances than those based only on sexual preference. And in a country where Brexit and competing nationalisms—English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish—are pulling the country in multiple directions, solidarity across lines of sex and gender is essential if the nation is to be protected from a gray future of Tory austerity and ever greater social inequality. But whether “queer” should be deployed retrospectively to organize highly diverse artists and artworks is another matter entirely. That’s the question raised by Queer British Art: 1861-1967.

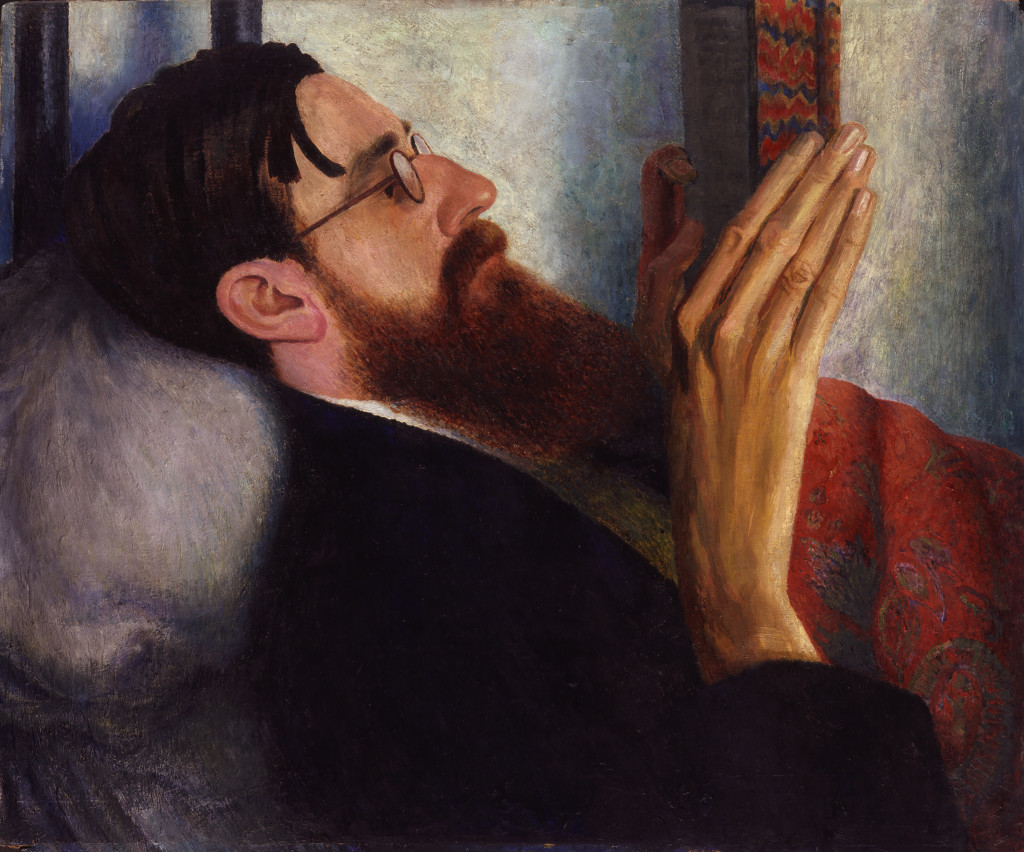

The bracketing dates of the Tate exhibition mark the elimination of the death penalty for sodomy, and the decriminalization of sex between men. But the 100 years between were not ones of continuous progress in acceptance of what came to be called “homosexuality.” Far from it. The decades from 1880 to 1920 were particularly oppressive, which is ironic because it was also the time of Oscar Wilde, the gay rights advocate Edward Carpenter, and the novelists Lytton Strachey, Radclyffe Hall, and Virginia Woolf. All are represented in the exhibition by fine, painted portraits. (See especially Dora Carrington’s loving rendition of Strachey reading.) Add to that the growing popularity of male and female impersonators in vaudeville—enjoyed as family entertainment— and the period seems like a veritable queer, golden age. The campy, promotional photos of Malcolm Scott and Maude Allen as Wilde’s Salome (1905 and 1908), suggest a broad understanding that gender was a performance and everyone an actor. But what was mooted in the music halls was denied elsewhere. “Gross Indecency” between men was criminalized in 1885, cruising was targeted for prosecution in 1912, and in 1921 a bill was advanced to prohibit lesbianism. It was defeated in the House of Lords on the grounds that most women didn’t know what lesbian sex was. Had their Lordships seen Dame Ethel Walker’s Homeric mural of 30 naked and self-adoring women (The Excursion of Nausicaa, 1920), they might have come to a different conclusion.

Succeeding decades saw only intermittent progress in gay liberation. Prosecutions for buggery, sodomy, indecency, and all the rest continued right up to decriminalization in 1967 and even beyond. In 1988, Margaret Thatcher helped pass Section 28 of the Local Government Act, stating that no local authority “shall promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.” By then, however, the broader culture had moved on. The artists Francis Bacon and David Hockney had for decades represented gay men and gay sex in their artworks and achieved tremendous public acclaim. Bacon’s Figures in a Landscape (1956-7) stages a nude, erotic embrace on a round platform or stage-set. The diagonal dashes of red among the predominant gray-blue hues suggest the artist’s well-known preference for masochism and rough-trade. Hockney’s Bertha alias Bernie (1961) shows a towheaded young cross-dresser or drag queen, perhaps the artist himself. The figure is painted crudely, like something by Jean Dubuffet, and stands on spindly red legs above an outlined bent figure. To be “bent” in Cockney and others slangs, is to be gay.

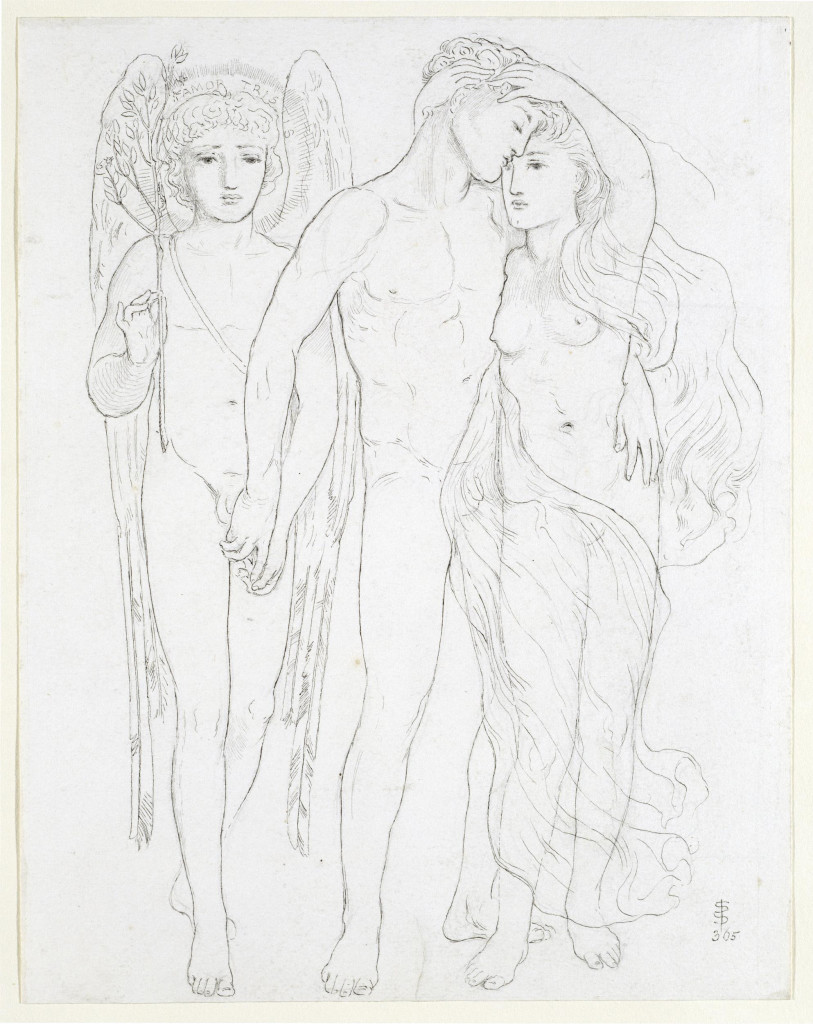

In 2000, Parliament passed the Sexual Offenses Amendment Act decriminalizing group sex and lowering the age of same-sex consent to 16. A Civil Partnership law was passed in 2004, and same sex marriage in 2014. The Tate exhibition thus arrives at a propitious moment: a great civil rights victory has been won and the full history of the struggle must now be written. Queer British Art is part of that accounting. It implicitly argues that the achievement was the result of a century-long, broad-based effort to make visible modes of behavior, comportment, and sociality that were previously forbidden and hidden. And that in so bringing these into view, artists, writers, and activists forced public forbearance and finally achieved political acceptance. The pioneers in the struggle we learn, such as the brilliant and tormented Simeon Solomon, paid a heavy price. His Bride, Bridegroom and Sad Love (1865) tells the story in a single drawing: the bride’s hands enfold the groom’s head, while the groom extends one hand around his bride’s waist, and the other behind him to hold the hand and fondles the penis of an ephebic angel with downcast eyes. Solomon was charged with attempted sodomy in 1873 after being arrested in a public toilet, and from that moment on his career was ruined. Wilde was imprisoned for Gross Indecency in 1895 and emerged from prison a broken man. Subsequent generations, however, saw ever greater acceptance of same sex desire: in the theatre, the cinema, the nurturing confines of Bloomsbury, the fashion studios, Soho, and in galleries and museums such as the Tate itself. And through it all, the champions of liberation we learn, we’re queer: not necessarily gay, lesbian or transgender, but open to the prospect of alternative loves and sexualities.

There is a great appeal and considerable explanatory power to this narrative, but there are also problems with it. As I have already argued, there were vain victories and significant setbacks along the way, and satisfaction at the ultimate achievement of gay marriage is vitiated by the nature of the political and social space in which it has occurred: a neoliberal regime which appears increasingly illiberal in its turn toward racism, nationalism and xenophobia. (And here I am thinking of the United States as much as Britain.) While the achievement of gay marriage under a Tory government leaves no taint, it should give pause. The century long struggle for gay rights, represented by the pictures in the Tate exhibition, may not have been the product of judicious queers so much as outlaws like poor Simeon Solomon and shattered Oscar Wilde, who broke laws, flouted decency, chided capitalist culture, and embraced Socialism.

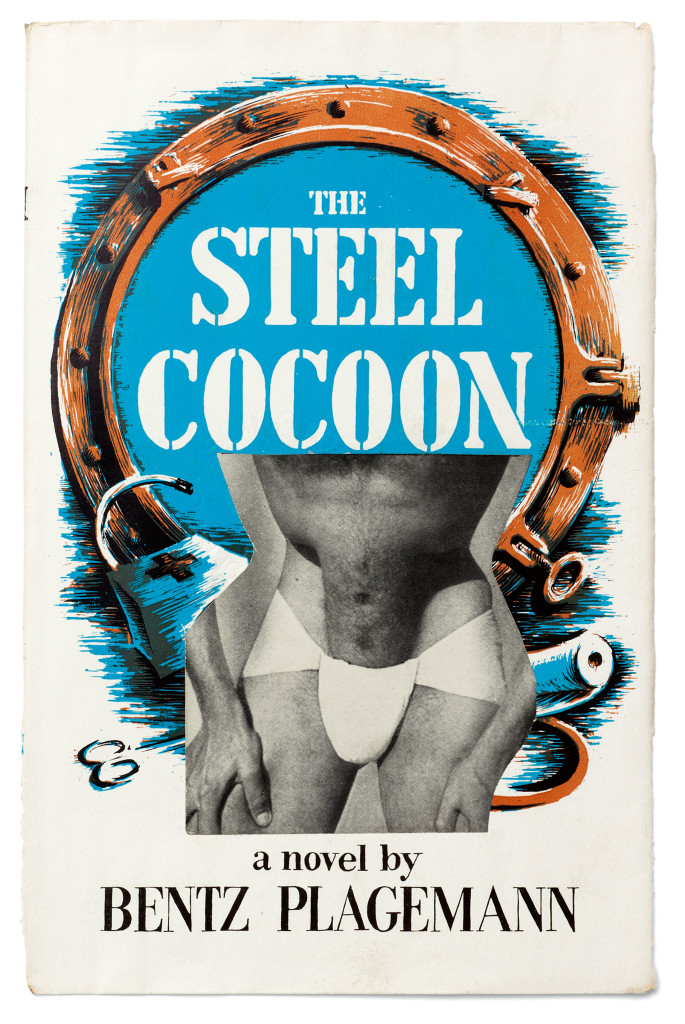

Among the most arresting, touching and hilarious objects in Queer British Art, are Kenneth Halliwell and Joe Orton’s book jacket collages. Between 1959 and 1962, the two young writers (and lovers) borrowed books from Islington libraries and cut, collaged, transposed and replaced their covers. They then returned the books and surreptitiously watched the reactions of staff and patrons. The technique recalls the revolutionary work of John Heartfield who used it in the 1930s to attack Hitler and Nazism. In this case, the covers subverted class hierarchies and sexual proprieties. The jacket for the historical novel Queen’s Favorite showed two, semi-nude male wrestlers in a clinch. The title for Emlyn William’s anthology of plays was changed from Might Must Fall to Knickers Must Fall, etc. Halliwell and Orton were eventually arrested for their defacements and sentenced to six months in prison. The reason for the harsh penalties, according to Orton, was “because we were queers.” But what Orton meant by the phrase was that he was engaged in a loving, forbidden, sexual relationship with another man, not that he was different from everyone and open to anything. With luck and effort, we may all soon become queers, but it took the struggles and sacrifices of gays and lesbians to get us to that point.

Queer British Art runs at the Tate Britain until October 1, 2017.