A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde // MoMA

by Anastasia Karpova Tinari

By 1917, the Modern Industrial Age had radically transformed society. WWI and concurrent social revolutions questioned whether the advent of electricity, trains, cars, would result in the destruction or betterment of humanity. Artists throughout Europe responded with radical movements—Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, and Dada—that increasingly threatened Academic tradition and figurative representation. However, nowhere did experimentation occur more quickly and profoundly as in Russia during the 1910–30s; artists not only pictured, but shaped the revolution—re-imagining the essence, purpose, and role of art in society. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York—whose collection holds the largest body of the Russian Avant-Garde outside of Russia—this year celebrated the centennial of Russia’s 1917 revolution, organizing a sweeping survey of 260 works across departments of drawing, prints, film, sculpture, painting, costume design, photography, and utilitarian objects.

One might expect MoMA’s exhibition on Russian Avant-garde to open with its fine examples of Suprematist or Constructivist works by Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, or László Moholy-Nagy. However, breaking this assumption and showing instead the museum’s own increased experimentation, Revolutionary Impulse opens with relatively unknown works by women. Olga Rozanova’s linoleum cut Voina (War) Portfolio (1916) is an energetic Cubist, Futurist array of rifles, cities, bodies, workers, diggers, and battlefield combat. An artist and activist, Rozanova produced an impressive amount of work before her premature death from diphtheria at age thirty-two. Included alongside this work is her dynamic Cubist painting The Factory and the Bridge (1913), as well as book illustrations done in collaboration with her husband Aleksei Kruchenykh. Work by pioneering filmmaker Esfir Shub’s The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927), similarly opens the exhibition—a seamless, enthralling montage of archived footage of the October Revolution. Shub, an early feminist filmmaker credited as the creator of compilation film, generated historical documentaries meant to evoke a revolutionary spirit, also writing an unexecuted script entitled Women (1933–34) on their role throughout history. With this opening context, exhibition curators Roxana Marcoci and Sarah Suzuki, along with Hillary Reder, point to a truly rare and revolutionary situation of women working equally beside men. Throughout the galleries of Revolutionary Impulse, works by artists like Varvara Stepanova, Natalia Goncharova, and Lyubov Popova hang in conversation with their male colleagues, a pivotal epicenter of this revolutionary movement.

Iconic Suprematist and Constructivist works by Kazimir Malevich, Naum Gabo, El Lissitzky, and others follow. Malevich’s paintings, prints, and drawings are installed salon style, as they were in 0.10: The Last Futurist Exhibition (1915) in Petrograd—the first exhibition that asserted his new Suprematist style. Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying (1915), a floating assemblage of black, yellow, and red rectangular forms; Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack–Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension (1915), a simple black square with a smaller red one tilted diagonally off its axis; and the large White on White Suprematist Composition (1918) shows his non-representational progression, finally eliminating color, Malevich’s last trace of figure and ground. Naum Gabo’s celluloid, ephemeral Head of a Woman (1917-20) and Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction (1920) are remarkable sculptural experiments in three-dimension, rotation, and shadow. Spatial Construction, originally exhibited at the 1921 Second Spring Exhibition of the OBMOKhU (which translates to The Society of Young Artists) typically hangs in MoMA’s galleries, but is here given full context amid the artist’s precise, graphic ink and gouache drawings from the same year. Almost an entire gallery is given to Lissitzky’s 1919–1927 project Proun (an acronym for “project for the affirmation of the new” in Russian). Architecturally and formally rigorous geometric shapes carve out space on canvas and paper, re-conceptualizing and visualizing a fundamental societal transformation, which artists anticipated the Revolution would bring. The Proun portfolio of eleven lithographs is on view for the first time since its 2013 acquisition; MoMA’s set is the only one of six that retained its front and back covers and inner folio. However, certain moments reveal the exhibition is only as strong as MoMA’s permanent collection—while Lissitzky’s Proun is represented in depth, Vladimir Tatlin’s works are only exhibited through pamphlets and ephemera. Nonetheless, the exhibition demonstrates remarkable breadth of experimentation, far beyond Suprematism, Rayonism, Constructivism, and other –isms, neatly filed away into academic art history timelines. The artists in Revolutionary Impulse called basic tenets into question: words, sense, image, and art’s role in society. With the world turned upside down, breaking with tradition became less intimidating and more urgent.

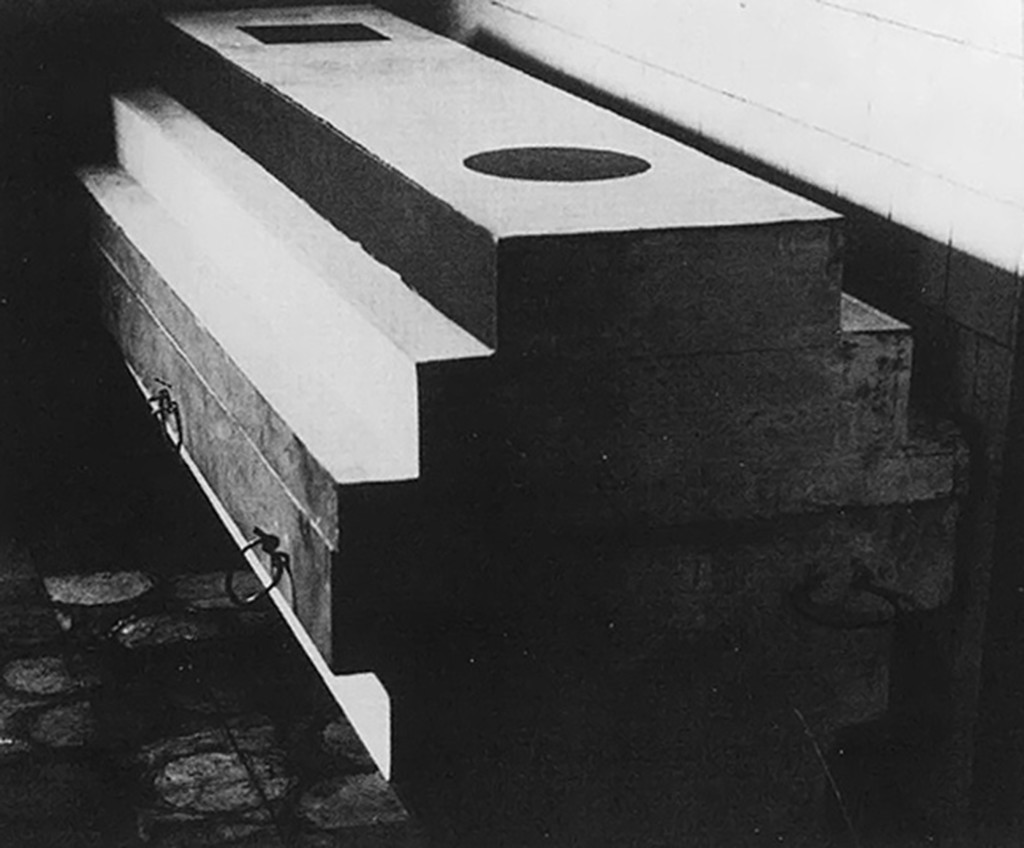

One of the most exciting aspects of Revolutionary Impulse, is the seamless flow between media typically sequestered to different galleries: paintings, books, drawing, photography, graphic design, sculpture, and film all work together to present social subversion. Nikolai Suetin, a close follower and friend of Malevich, extended Suprematist painting to ceramics and kitchenware. Suetin would later create a Suprematist casket for Malevich, the ultimate sign of devotion to his artistic cause. Alexandra Exter’s Stage Sets (1927–30) are extraordinary pochoir treasures: graphic compositions akin to Lissitzky’s Proun, which served as Constructivist stage set designs, such as Shakespeare’s Othello. Russian Futurism movement, formed by artists and writers including David Burliuk and his brothers, Natalia Goncharova, Aleksei Kruchenykh, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, who united under the 1912 manifesto “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,” most dramatically overturned order in language and performance. The 1913 Futurist libretto Victory Over the Sun was written in a new “trans-rational” language entitled Zaum, experiments in sound symbolism and linguistic creation. Poets and painters collaborated to disassemble words for their visual and Constructivist purposes. Rozanova and husband Aleksei Kurchenykj created Zaum poetry books, while Lissitzky and Malevich’s made On New Systems in Art: Statics and Speed (1919), a book that interwove language and lithography.

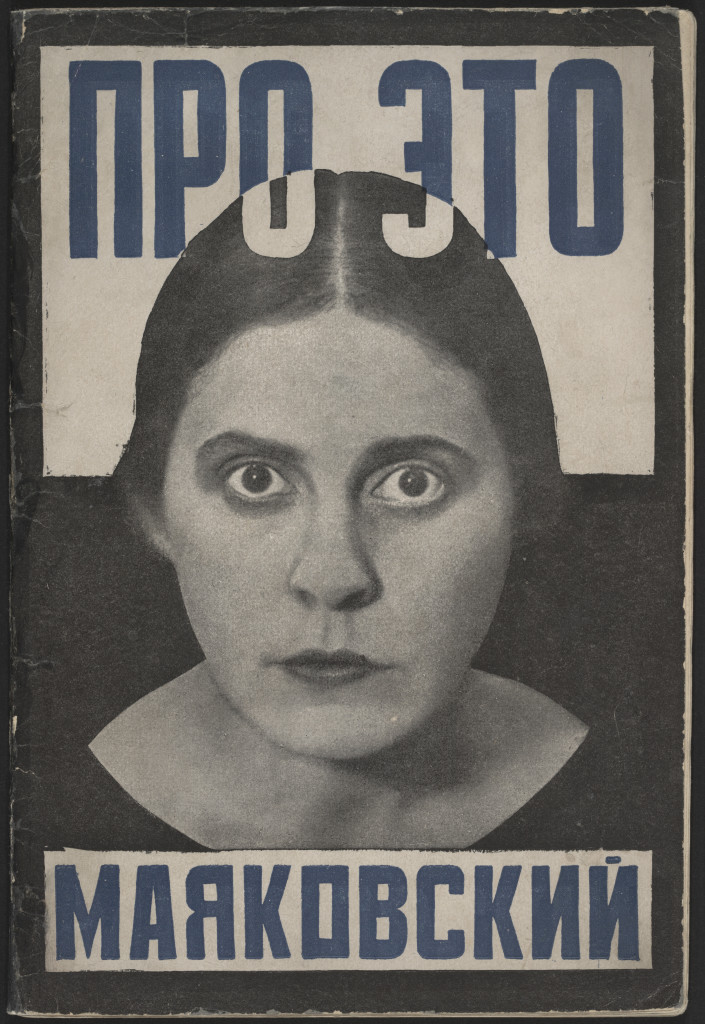

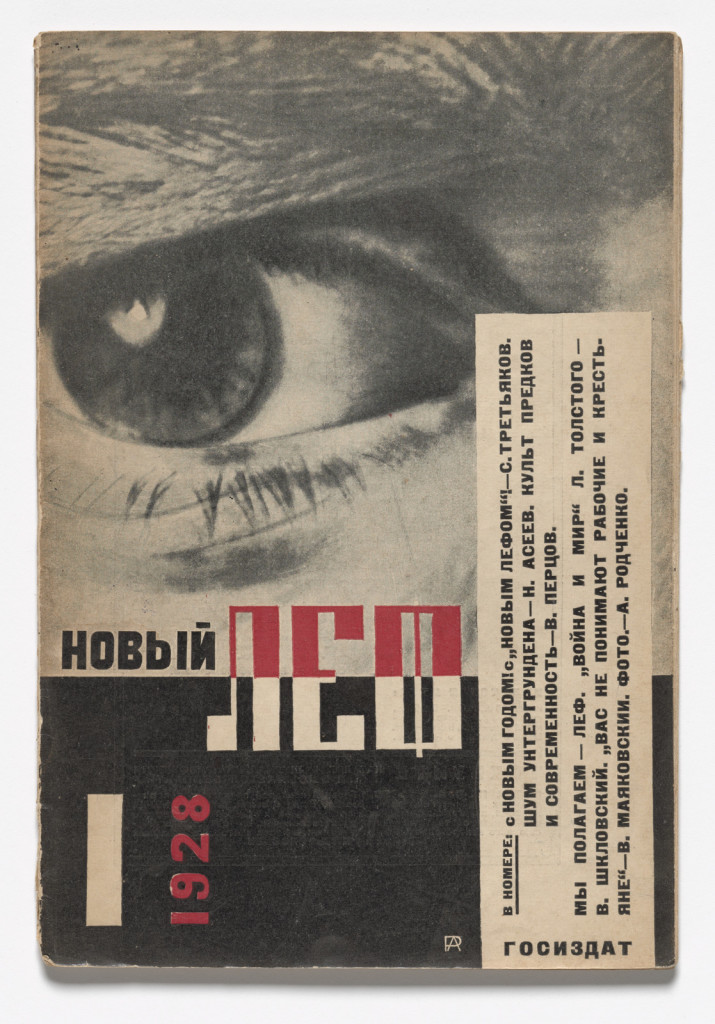

Words also had the power to organize. Avant-garde writers, photographers, critics, and designers gathered associated as the group LEF and published an eponymous journal to “re-examine the ideology and practices of so-called leftist art, and to abandon individualism to increase art’s value for developing communism.” After the original 1923–25 run, a new edition of LEF (Journal of the Left Front of the Arts; Novyi LEF: Zhurnal levogo fronta iskkustv), was published in 1927–28. Aleksandr Rodchenko illustrated the covers of all twelve issues, laid out in a long vitrine within Revolutionary Impulse. Compared to Masses, America’s earlier radical artists and writers’ publication filled with expressive, gestural illustration, LEF is extremely geometric, organized, and carries through the allover Constructivist aesthetic.

Revolutionary Impulse also scratches the surface of experimentation in film through four 35mm works looped in a designated film gallery: Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother (1926), Alexander Dovzhenko’s Zemlya/Earth (1930) Sergei Eisenstein’s famous Potemkin (1925), and Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera (1929), which films city, factory, and production through the “cine-eye,” the camera lens’ novel conception of the world. As technologically revolutionary as they are, the films portray direct revolutionary entiment and veer toward the propagandistic. Vertov further worked with Rodchenko to produce newsreels titled Kino-Pravda (Cinema Truth) to promote a revolutionary agenda by

“Filming facts. Sorts facts. Disseminating facts. Agitating with facts.” Vertov’s montage reel at MoMA documents Lenin’s life and death and the resulting national mourning; the film echoes Shub’s Romanov, cycling through Russia’s ever-repeating history of deposed dictators and revolution.

Splicing together images was also widely used in photography, as seen in an entire gallery dedicated to photographs, mostly by Lissitzky and Aleskandr Rodchenko. Lissitzky’s photo-montaged images from mass media, poster designs, book covers, advertisements, and postcards—his radical Self Portrait (1924) shows the artist’s face consumed and overlaid with Constructivist assemblage. In the 1926 gelatin silver print Record, a track runner leaps over a hurdle, with Broadway at night whizzing by in the background; the picture is composed entirely of images taken by other photographers, an example of Lissitzky’s fotopis (painting with photographs). Rodchenko’s experimentation was more in cropping and composition. His subjects celebrated the communist worker and citizen: a young pioneer girl, with her eyes fixed determinately into the future; workers on the rigs of a construction site, or portraits of his fellow revolutionaries, the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and Varvara Stepanova.

Revolutionary Impulse whirls through a bright historical spark of possibility, innovation, and re-thinking of art as integral within new society. By the 1930s, this bright spark faded as Stalin’s regime shut down experimentation and strictly enforced Social Realism; a more directly and easily consumable avenue for revolutionary propaganda. Russian politics are not portrayed as didactic in the exhibition, but rather, inherently frame the context of the works—all art is political, but in this brief historical moment, the lines blurred and art and politics became one indistinguishable, electrical current.

A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum of Modern Art in New York ran from December 03, 2016–March 12, 2017.