Sadie Benning: Shared Eye

by Kate Pollasch

Viewing Sadie Benning’s 2007 video work Play Pause is to be enveloped in a slow submersion of textural sounds, tactile traces, banality, and erotic intimacies that seems to unmask something indefinably true about living in Chicago. It is a work that lingers, like a shadow, coloring one’s own experiences from the exhaustive pleasure of sitting down in the CTA train car after bracing against merciless winds, or in the delicate moments of laying in the darkness listening to the chug clank tick of Chicago pipe heaters in so many of our apartments. These sensory pulls can easily lead back to first viewing Play Pause. Benning’s practice has since shifted and evolved from this work within her early video practice, but there remains a distinct form of looking—a uncharted way of visually communicating—that consistently resonates long after viewing. Returning to Benning’s Midwest roots, The Renaissance Society opened Shared Eye, a new installation of mixed-media panels that will bring the city and the artist back together again.

Since the presidential announcement was made during the dark night of November 9, a call to arms to protect what has been achieved and what hopes lie in human equality, eco-consciousness, international relations, and more are erupting across America. In this, Benning’s return to Chicago through the exhibition stands on the front lines of unacceptance, standing against the new America we face. According to the Renaissance Society, “Shared Eye highlights how internalized and automatic the pervasive surveillance-like affect of Capitalism and its attendant structures of patriarchy, misogyny, racism, and xenophobia can become. The artist illustrates, in both poetic and critical terms, this associative construction of meaning: for Benning, it is imperative to name and disrupt this system of organizing information, as it relates to this particular moment of deep political uncertainty.” In what could be the most imperative time for this exhibition, I had the opportunity to speak with Benning and Renaissance Society Chief Curator Solveig Øvstebø about the exhibition, Benning’s practice, and Midwest roots.

Kate Pollasch: Sadie—your career has such strong ties and beginnings with the Midwest. In thinking about these Midwest roots, I am wondering why now, why did it feel like the time to exhibit this body of work in Chicago and at the Renaissance Society?

Sadie Benning: The show came about because I was invited by Solveig Øvstebø. I had lived in Chicago for seventeen years, and grew up in Milwaukee. I have always spent time between two places, I grew up with divorced parents so no one place was primary.

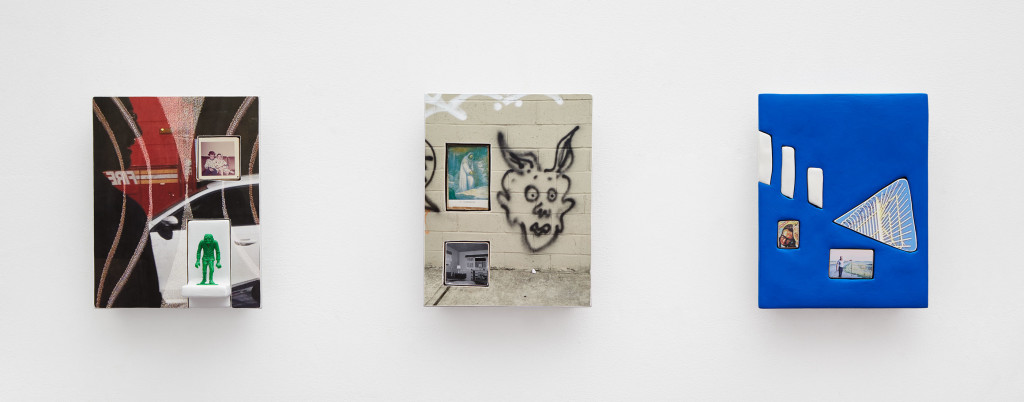

Solveig Øvstebø: I had followed Sadie’s work for quite some time before I invited them to do the show here at the Renaissance Society. The way the work developed from films to paintings, and yet at the same time totally blurred the lines between the different mediums, was intriguing. Standing in front of their work it is hard to conclude on any set description. Is it a sculpture? A painting? A photo? Or are we in fact standing “inside” a film where the images the works we see are individual frames. I was interested in this ambiguity that surrounded their work, both on a concrete and material level, but also thematically. It is open and unresolved in a positive way.

KP: The works in the exhibition are in dialogue with the artist Blinky Palermo—specifically his 1976 exhibition To the People of New York at DIA. Can you speak a little more about your artistic interest in Palermo? How did you become influenced by his practice, and why did you specifically want to engage with his 1976 exhibition?

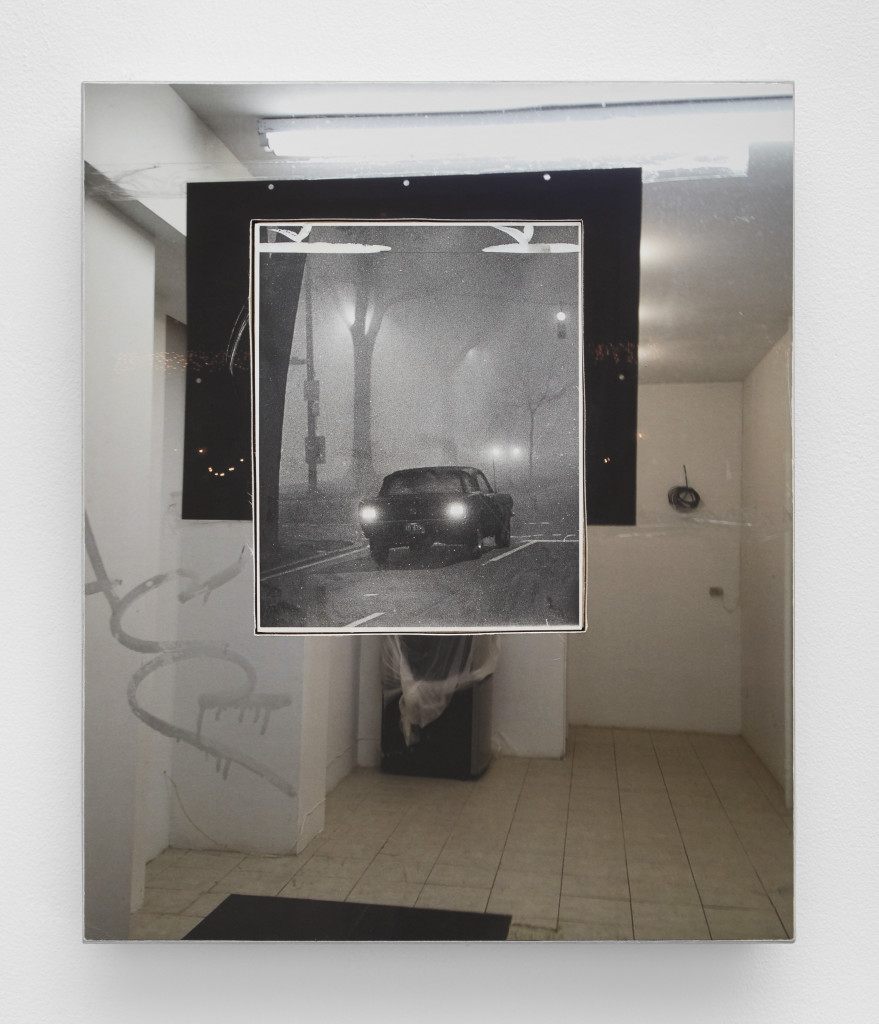

SB: I have been interested in Palermo’s work ever since I first saw it at DIA years ago. I liked the relationship between its structural, mechanical properties and its human and more tactile qualities. It spoke to a contemporary feeling or condition that I related to. The interest in working with the mathematical parameters came about because it made sense within the content of the work. The Shared Eye show is a lot about how perception is developed and how seeing is built upon a spectrum of factors. There is a ghostly quality to how we look and think, so I was interested in having a trace of another work, and specifically the way that To The People Of New York City, functions in terms of sequencing scale shifts and the relationship between the singular and the group, as well as the frame or banding that happens inside it. There is a cinematic quality to it. In working with Palermo’s math, it changed the framing and ideas I was having, so it became more improvisational as a process.

KP: The Palermo 1976 exhibition was as much about the work as it was about the installation—a very prescribed hanging style that was often associated with the pulse of Jazz. Your upcoming exhibition is framed as “working within the parameters set forth by the structure and progression of Palermo’s installation…” How did you and Øvstebø navigate working within Palermo’s parameters in the context of the Renaissance Society’s distinct space? How much has the physicality of the Renaissance Society influenced or altered the curatorial layout?

SB: The Renaissance Society has gone through a lot of transformations since I was living in Chicago—the space was remodeled and no longer has the gridded light ceiling. It is a very tall and dominating space, kind of spaceship meets church. The idea to work with a fixed structure inside this architecture, one that is open-ended but suggests a sightline that is orderly, and—much like the timeline of frames one sees when editing video—seemed to be a way of trying to interject another focal line into the space.

SO: For this particular project, the installation had less to do with relating to the specific architecture of the Renaissance Society. We were thinking back to Palermo’s original installation to create a space and a setting that resonated with that presentation.

KP: How long have you been working with photography, and do you see it as having a dialogue with your video practice?

SB: Photography has always been more of a referent or underlying factor in my working process because I would often take hundreds of analogue photographs and use them as parts of a whole—like in the video Play Pause which is all drawings. I would cut up and trace parts of photographs I had taken, merging three separate cities into one to create a background or space that was part imagined and part ‘real’. I see framing a still image or framing a moving image as being related, so I do not break down the categories of what I do in terms of the equipment or the tools. It is hard because with video I started recording on a cassette tape and moved to VHS, hi8, 3/4 inch, 1 inch, digital beta…it seemed that even if I wanted to be a video artist or claim that, it was constantly changing and morphing. I started spending more time in the studio with paper and pencils gouache, canvas, gesso, wood, screws and flashe paint. I decided I would not hold myself to any one thing or form, I would work openly to where the ideas would take me.

KP: What is your process like when working with photography?

SB: It depends on what the work is— in the past, I have taken photographs, developed them, blown them up on a Xerox machine, traced parts with graphite paper, colored in the drawings with black gouache, filmed parts of the drawing, and then edited them with sound into a video. I knew I wanted with Shared Eye to have content within each panel, so there was a process of selecting observational images with found images and objects that would create narrative possibility and meanings. I made a series of drawings and videos called Ghosty Jr. in the mid-1990s—a cartoon ghost with one giant ear and tennis shoes, that would overhear and observe. It was drawn on a long scroll. I think I wanted Shared Eye to have a similar quality of the observer, and the feeling of looking or being looked at. I also found that the photographs obtain so much projection because we do not know who the people are, so we project our assumptions and our own feelings onto them. I wanted to think about representation in the works, and how memory is constructed through documentation and illustration.

KP: The exhibition text discusses how destabilization and ambiguity can assume a political dimension. National politics are at the forefront of America’s consciousness, and when your exhibition opens America will have a new elected president. Your practice also has deep roots in gender and sexuality politics. Will you expand on the political dimension of this body of work and how/if you see it in conversation with the current political atmosphere in America?

SB: The work is conveying sets of associative relationships, and is open to interpretation, so it might suggest a number of reads or possibilities. I feel like during this pre-election time, there is a sense of fear, of not knowing, and concern for where the United States is going. So, there is the unknown and questioning—but also intuition is an important part of Shared Eye. So much has been done to stop people from questioning or dissenting, to stop people from having an intuition if it varies from what the government wants us to believe. It is easy to feel you are paranoid if you question something these days. Atmosphere is a key word—even when one is thinking about form and structure, politics are embedded; an audience brings with them all kinds of histories and political ideas. With Shared Eye in particular, there is no one political way of seeing it, there is too much going on. It is more of a collective network of associations—I certainly have my own feelings and ideas inserted, but I do not insist that there is a single correct way to see it.

Sadie Benning: Shared Eye at the Renaissance Society runs through January 22, 2017.