Shadow Shift: Afruz Amighi

by Kostas Prapoglou

Afruz Amighi is an Iranian-American sculptor and installation artist based in Brooklyn, New York. In 2009, she received the Jameel Prize for Middle Eastern Contemporary Art, an award by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for her work 1001 Pages (2008), inspired by Iran’s Islamic traditions. In 2011, she was granted a fellowship in sculpture by the New York Foundation for the Arts, and two years later her work was commissioned among sixteen others by nonprofit contemporary art organization YARAT for Love Me Love Me Not, an exhibition held during the 55th Venice Biennale. In the summer of 2018, the Frist Center for Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee will present her first major museum exhibition. Speaking with Amighi on the occasion of Echo’s Chamber, her first solo show in the UK at Sophia Contemporary, the following discussion covers the artist’s recent turn toward a self-identified nationality in her work, the history of violence, and the nuances born of manipulated light and shadow.

Kostas Prapoglou: What are the sources of your inspiration and what is the process of incorporating them within your visual lexicon?

Afruz Amighi: I often feel that I have no fixed point in my work, as my interests tend to migrate over different times and places, and first-generation artists are often expected to have a limited focus. But there is a fixed point, or a fixation for me, at least on history, and how it creeps, often insidiously, into the movements, words, and actions of our everyday. I am interested in the tipping point in any given society between peace and war, whether this manifests as a war between nations, sexes, races, etc. What is the nature of that moment of eruption, when the containment of quotidian violence no longer holds, when things fall apart?

While the world has grown less violent over the ages, our anxieties about violence have become more pronounced— and it is this anxiety that preoccupies me. Until very recently, this fascination led me to explore the history of the Middle East, as here in the United States, we were living temporarily under the illusion of civility. However, as the Trump victory exposed the ongoing subterranean civil war, the US has become my subject matter (as vast as that may seem), as well as my self-identified nationality, for the first time ever.

These ideas seep into my work through literature and music. I do not often look at fine art—I was not raised with it, and it does not feel natural to me. In fact, in terms of literature, I have had a reader’s block for many years, so often the history that I consume is secondhand or based on accounts of accounts. But music is the landscape of my studio, and when one listens to it twelve hours a day, one analyzes, dissects, and often does impromptu interpretative dances when no one is looking!

KP: Do your ancestral roots haunt the way you interpret contemporary Western realities, and the way you juxtapose these against Eastern counterparts?

AA: Well, yes of course! I feel like an American-ish person living in Babylon (i.e. the US), and the hope is that every human in the world would feel similarly about their respective countries. I mean, the birth of every nation has been predicated upon genocide and artificial notions of ethnicity. But I suppose when you are the ‘other’ it gives you a disadvantage in terms of power, but sometimes gives an advantage in terms of insight.

My first memories of exclusion are from being a child and being terrified of the police or anyone in uniform, and of things like the American flag and the pledge of allegiance. Obviously, at ten years old, I had no analysis—these things just felt dangerous, like a rowdy club that I could not join. But they have indelibly shaped my sensibility, aesthetic, and perspective.

Having said that, I do not think any nation or group has the moral high ground on any other. Given the chance, I think oppressed peoples and nations would likely inflict the same violence upon ascension of power as their predecessors (hence my previous reference to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart). My project, rather, has been to explore a more general question, a question that consumes many and will perhaps always remain unanswerable, and that is whether humans are inherently violent creatures, or whether this tendency can be uncultivated. Easy listening, I know.

KP: To what extent does your chosen narrative affect the materials you use each time?

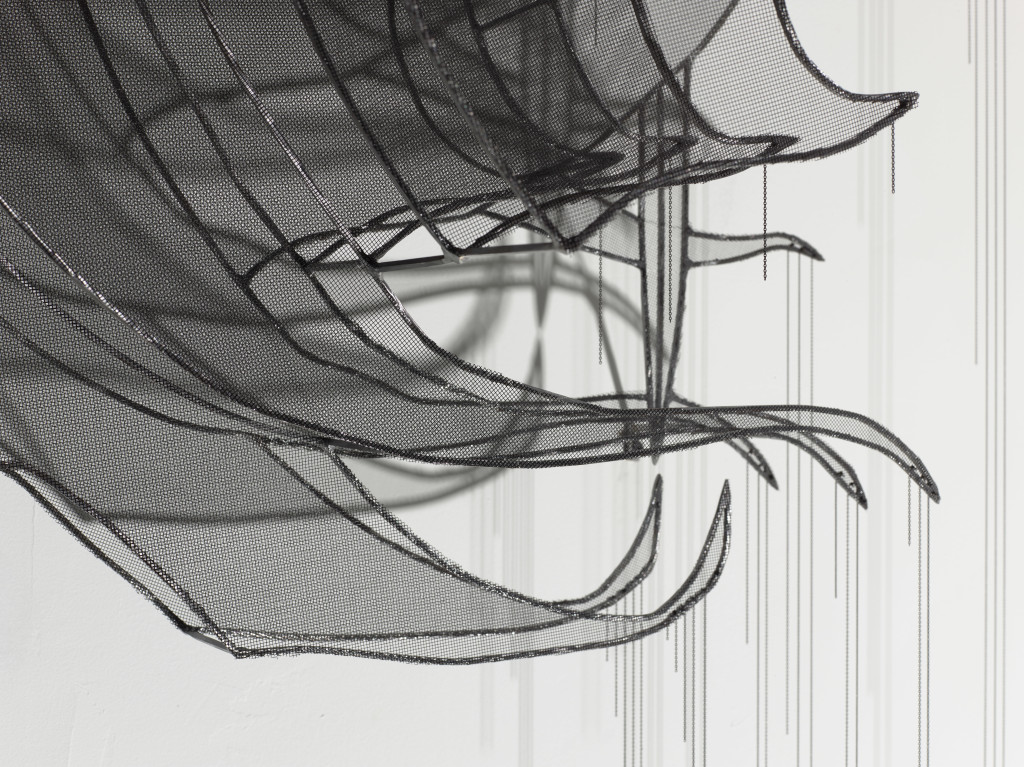

AA: I have no conscious understanding of how my concepts drive my material choices, or vice versa. What I can say is that I am fickle, and after a few years of exploring a particular narrative or material, I get bored, my eyes wander, and if I do not break new ground on either of these fronts, I face spiritual death, not to be melodramatic or anything—but speaking of drama, I think the only constant in my work so far has been the theatrical manipulation of light to create shadow.

I like the extremes of light and dark as well as the nuances created inbetween. I want the viewer to feel immersed and alone in the work, and to experience something beyond the marks I make on paper or in steel. Light enables this for me—as shadows cannot be nailed down, they also cannot be accounted for; they shift, just like narratives. Now I sound like a post-modernist, oh well. But really, the lighting in my work is usually the last step in the process, and always comes as a surprise to me. This unknown outcome— how the light will reflect itself on the material, how it will cast shadows—is what I find most exciting, because it is not completely under my control.

My current materials, steel, fiberglass mesh, and chain, are things used in building construction— I discover most of my materials in the industrial sites I pass everyday on my way to my studio. I remember for years watching the way the frames of buildings were erected, draped in mesh, and lit from within during the night. I finally asked a construction worker where I could purchase the materials, ordered them in bulk, and they sat in my studio for a year before I figured out how I wanted to use them.

KP: Would you say your work is political, and why?

AA: I would say my work is political, but I think that all art— all culture—is political, whether the intention is there or not. Personally, I do not set out to make any political statements in my work at all. The very thought of doing so is an anathema to me.

I work from a visceral place, and the ideas I have in my head going into the process are very fragmented. It is almost always in hindsight that I better grasp the concepts I was working with. It is like looking down from an airplane and seeing a pattern, which when on the ground only appeared to be random scatterings.

I work with dualities, arranging bundles of contradictions alongside one another, all the while trying not to judge the imagery that pours out onto paper. This can be very difficult, because neither life nor art fits into neat and acceptable slogans or imagery.

In preparing the works for my recent show Echo’s Chamber, I did not want to shy away from the internalization of oppression that plagues even the so-called ‘strongest’ of women. And so, these portraits came as my attempt to understand for myself how the daggers of sexism come at us both externally and internally.

I wanted my women to be real, like the women in my life, who are neither ‘victims’ nor ‘heroines,’ which are really just flip sides of the same flat coin.

KP: Your work has been exhibited in various parts of the world. Do you detect different readings and approaches of your work by local audiences depending on regional socio-cultural characteristics?

AA: I wish I had more of a sense of this, because I am sure there have been distinct reactions to my work from region to region. I hear snippets of people’s reactions at openings here and there, but the only thing I have been able to glean is that I sense that there is more fluidity around notions of identity in the UK than there is here in the US, even post-Brexit.

Here in the States, and I think this is starting to shift, there is more of an emphasis on hyphenation, especially if the artist was born in a non-Western country. For a while, I noticed that American art critics were referring to artists of color as “global artists.” It was a clumsy code word for the artist not being white, much like when newspapers refer to “urban youth,” when what they really mean is young African-Americans. It is just a semantic cover for racism.

KP: How do you see your practice evolving in the following years? Do you see this interplay between light and shadow playing an equally important role as it does now?

AA: I suppose rather than evolve, a word that connotes a peaceful transition, my work tends to break with itself every few years, in a rupture that never feels organic or easy. At this point, I find myself more engrossed in drawing than in sculpture, which is new, as in the past, drawings were only a means to an end for me, mechanical sketches intended to serve as guides for sculptures.

Now, drawing has become an end in and of itself, and I am enamored with being free from the constraints of physics, gravity, the limitations of materials, and being able to create imagery on paper that would never work in space.

Maybe I am drawing also to avoid the fact that I am reaching a point with my sculpture that is starting to feel formulaic. I am dreading the fact that this summer, I will likely be in that experimental phase again, testing new materials, new forms—a place that many people think of as exciting, but that I find terrifying.

The constant for me is light and shadow. I think this will continue to be an integral part of my work. It comes from the way I feel when I am in a church or mosque, where the dramatic lighting allows for a solitude and a sense of communing with something or someone, at once.

This is an atmosphere I have always wanted to inject into the traditional art space, the gallery, the museum. With light and shadow, I find a preciousness in materials that normally might seem banal, mass-produced, but which then become something outside themselves: singular.

Afruz Amighi (b 1974, Iran) was the inaugural recipient of the Jameel Prize for Middle Eastern Contemporary art awarded by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 2009. She completed her Bachelor of Arts in Political Science at Barnard College at Columbia University, before going on to complete her Masters of Fine Arts at New York University. Her work is included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Houston Museum of Fine Art, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and The Devi Foundation, among others. She has exhibited in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Amighi currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.