Solution, Problem, Problem, Solution: On the Art of Luis Camnitzer

by Ionit Behar

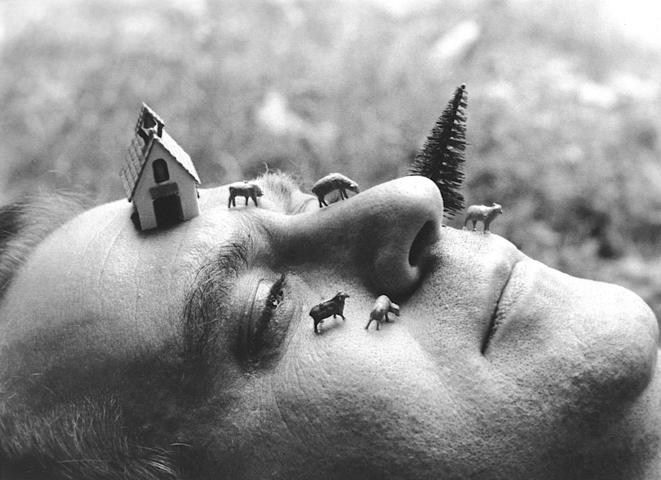

German-born Uruguayan artist and writer Luis Camnitzer moved to New York in 1964. He was at the vanguard of 1960s Conceptualism, working primarily in printmaking, sculpture, and installation. Camnitzer developed a body of work that explored language with both humor and politically charged strategies, and has been shown at important institutions since the 1960s. We met at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and quickly walked through an exhibition of Dada planned by Tristan Tzara in 1921. Afterwards, Camnitzer and I spoke about his first experiences in New York and the relationship between the center and the periphery that he perceived. He revealed that his main artistic strategy is to find a solution to a problem, or a problem to a solution—he approaches this strategy in part through “poverty-thinking.” A transcription of the conversation is below.

Ionit Behar: At the time you moved to New York City, one could argue that the hegemonic centers were changing Latin America. Can you explain how you perceived this happening?

Luis Camnitzer: The center was exerting political and informational (and military) pressure—in a word, colonization—something that my generation considered offensive to say the least. When I came to New York, however, there was some intellectual and cultural electricity in the place. Pop Art was coming up and climaxing, minimalism started to show, as well as conceptual art. All this made it influential. There were things happening, in terms of spectacle, so New York City was an interesting place, and Latin American artists looked very much toward New York. But it also was loud and dirty, and was not really a livable place.

IB: There is a lot of writing on the decentralization of the world, what do you think about that claim?

LC: I would agree—centers disappeared. I do not think geography is an important issue anymore. Maybe on the level of neighborhoods, but not much beyond that. The world is dominated by flows of information, and I would say there are some people who control information and some people who receive information. So the new center is rather ubiquitous. The periphery is formed by those who consume information and then are unable to counter the flow. For me, the analogy is in some ways an emulsified state; the person sitting next to you may be the center and you are the periphery, or vice versa. It is not based on a geographic situation anymore.

IB: Who were some of the people you found when you moved to NYC? What was the community of Latin American artists and other intellectuals who were your support?

LC: First, I have to mention the influence of Luis Felipe Noé, the Argentinean painter, with whom I shared an apartment during my first year here. The discussions with him took me out of crafts as a starting point to make art. At that time, I was a printmaker, and thinking in terms of craft. He kept telling me that printmaking was a secondary and minor way of doing art; he was right, but he did not realize that painting was also a minor, secondary way of making art. The exchange helped me see that I had to decide on what to do, more than how to do it. We then formed the New York Graphic Workshop, with Liliana Porter and Jose Guillermo Castillo, where we explored the limits of printmaking, and how to get beyond them. In that process, we arrived at something that later would be called “conceptual art,” although at the time we did not like the title for ourselves. We preferred to refer to our work as “contextual art.” We were looking at how a minimum input might produce a maximum output, and explode the senses and mind by making use of the context. It was not purely a matter of “dematerialization”, of using materials or not, everything depended on the circumstances. For me, that became something very connected to politics. There was also another friend in NY at the time, the Argentine architect Susana Torre; she, in turn, was a friend of Lucy Lippard and introduced us to her. Lucy was the person who opened the doors for us; at the time, the art scene in New York was very xenophobic and we had difficulties exhibiting.

IB: So the Latin American artists helped each other?

LC: Yes and no—I rather would say no. There was competition, and politically speaking, other artists were rather conservative. There was a moment when this was temporarily overcome, and we got together like a community. It was thanks to what now is called the Americas’ Society in NYC, at the time it was still the Center for Inter-American Relations, which was basically a front for the CIA that was used as a cultural façade. Some artists felt it did not do enough for them, others had political gripes. The board of directors at the Center was composed of individuals who were prominent symbols of U.S. imperialism in Latin America. At some point, we asked that the board resign and that they form a new cultural board. And that brought together the Latin American community, including both visual artists and writers. We started a boycott; the art director resigned in support of our ideas, but nothing else happened. I do not know what the place is like politically today, but I am probably the only one left that continues the boycott, although I am friends with the current director of the gallery.

IB: Some time ago we talked on the phone because, very generously, you offered to help me with the research for my dissertation. One of the questions I was dealing with was about Latin American artists working with sculpture and ideas of space. Very wisely, you said: space is not only present in sculpture or installation art, space is everywhere. And you suggested I look into mail art. This anecdote, to me, represents the way you think about material, and the way you work with language—the processes of language and thinking. Can you speak about how you perceive material?

LC: When you speak about material and non material you are basically talking about the borderline that separates them. In my work, I try to erase these borderlines, so it does not matter to me if it is material or not. What matters to me is that at some point of the creative process—either at the beginning or at the end—I end up with an interesting problem. At some point in the process, I will have to focus on that problem and hone in on its relations and implications. Then I have to compare the problem with whatever solution I am finding for it. Both must produce a perfect match, to the point where the two cannot be pulled apart from one another anymore. Sometimes, I end up with a solution for which I do not have a problem, and other times it is the exact opposite. What I find important is that in the process of answering a question, I may realize that the question I began with was not the right question, and that the answer is leading to another question. It is a very flexible multi-directional process of making connections, and by the end of the process, I can only hope that I will find a good match. So, it should not be predetermined if it is going to be a materialized thing or not; it does not matter. By the way, when the New York Graphic Workshop did mail art in 1967, it was because we needed an exhibition space, and envelopes seemed available and cheap. We were not really focused on postal issues.

IB: But once you have that perfect match for a problem and solution, a solution and a problem, then there is that next step.

LC: Yes, the next thing I have to consider is what I want to have happen with the communication, and what I want to generate. Whatever object I am presenting is not an end in itself, but rather a beginning for an important process that is not mine anymore. Until then, it is me and my presentation. The other part—from the artwork onward—is art as a cultural agent, and that is really what matters.

IB: You defined the term “Conceptualismo”—I wonder, if you could define it again, would you change anything?

LC: No, I think I am dogmatic, and I always continue believing the same thing. Conceptual art is a style and conceptualism is a strategy. The main break that happened with conceptual art, of hegemonic conceptual art, was to produce an art that took away, or minimized, the material. The material was considered an obstacle, and conceptual art tried to explore the essence of art. There was a mystical source of sorts in this kind of approach. In Latin America, and also on the periphery in general, art was more concerned with politics. The presence or non-presence of material was not a mystical issue, but one related to more general positions referring to the surrounding crisis. Under repressive regimes, the questions that artists were asking, and the messages they were communicating, were easier to circulate with dematerialized objects than with objects that had a heavy material presence. That led to questions, such as how one communicates information efficiently. The cultural context was not simply an art context, but a more complex situation of things that were happening at that time. In Latin America, for example, art was not really art as a restricted discipline, but more of an eruption of its general cultural and political context. So to compare the art of Latin America at the time with the art of hegemonic centers would lead to something that does not make sense. They might look alike sometimes, but the conditions were entirely different.

IB: It makes me think about the theories of new materialism that are now very present in academia, where the idea of material is expanded and given more power.

LC: Yes, but to some extent it is also continuing the craftsman’s approach to art—focusing on the art object, and seeing it less as an approach to knowledge. I think art is a trans-disciplinary or meta-disciplinary approach to deal with the world. I believe that a good education system should start asking the student to develop a personal utopia, and only then think in terms of art. Art for me is more general than science and includes it. Art deals with the predictable, like science, but also with the unpredictable, and therefore is richer. There is the ignorance of the predictable; mathematics in certain ways deals with that.; and there is the ignorance of the unpredictable. That’s wehere art comes in, which is what actually interests me about it. To learn how to think in art means to use imagination with no constraints. And that is done best within Utopia. And Utopia is important because it helps you to develop the ethics in the task. So now you have ethics with imagination. The next step then is ingenuity. Ingenuity is particularly clear in states of poverty. Ingenuity is actually a mode of poverty-thinking. We become aware of the limits of available resources, and try to expand them by connecting things creatively—multiplying the possibilities that are there without having to add anything. That is poverty-thinking. And lastly, there is the negotiation with reality, when you see what you are allowed to do and what you are not allowed to do. What is allowed depends on your resources and on the conventions or the laws of society. And then you know what you cannot do, but you also know why that is the case. You can identify what ways of communication are ethical and which are unethical, and that leads you to develop your politics. That is my construction, and if all this makes art or not is really irrelevant. Art is just a name and I do not care about the name.

IB: So an artist cannot be unethical?

LC: I think many artists are unethical because of a lack of examination. Once you examine your “concessions” or deviations from your Utopia you are, or should be, conscious of what you are doing and why. Here, you develop a kind of ethical cynicism that allows you to keep a critical distance from yourself, and wait for the right moment.

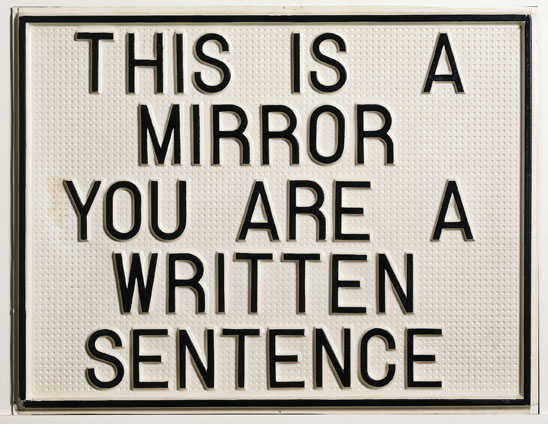

IB: The art you make reminds me of the Uruguayan economy where artists do not have the same resources or commercial galleries like, for example, in the U.S. Once, you said that you could conceive a piece consisting in taking the Empire State Building, and bending it into the shape of a U. That would cost millions of dollars but if instead you wrote: “The Empire State bent into the shape of a U,” it would be a much better artwork. Can you say more about this action? What led you to decide to write the sentences rather than perform the action itself, beside the obvious economic reason?

LC: Well, in part it is “poverty-thinking.” But it also takes into account where you want the work to happen. This example of the Empire State Building bent into a U shape, when I thought about it in 1966, I thought that first of all it is an absurd and useless idea. Second, I did not particularly like it, and third, were it to be built, it was totalitarian in its presence. But in thinking all that, I also realized that if I just described that image it would be created in the mind of the reader, so I did not really need the object. Then I thought, what is the purpose of having this happen? Is it useful, is it not useful? I realize that during the 1960s a shift took place in the history of art. Until then, there was a dialogue between the artist and the object (or the material), and the public was secondary in the process. As an artist, I was working for myself. It is a kind of dialogue still performed in certain art schools—where students are taught on how to do things, instead of dealing with what to do. When information theory came around as an important thing during the 1960s, suddenly artists focused on both, on who emits the information, but also on the vehicle and the receptor of that information. The recipient became very important, and the concern appeared about the possible loss and erosion of information during communication. These issues were picked up by conceptual art and by conceptualism. All these issues, for me, became clear with the use of language. At the time I wanted to see if I could use language as a photographic tool: to make a description that was so perfect, that anybody that would read it would conjure the same image in their minds.

IB: So there is always a problem and a solution, or a solution and a problem, in whatever order?

LC: Yes, I would say always. I often find the solution or the problem in the act of writing.

IB: It must be comforting in a way to know that you can find out if something is right or not.

LC: At least for as long it lasts. I think you have to bring your gut reaction to an absolute minimum. I am not saying you should get rid of it and, also, I do not think it is about explaining the meaning of the work. I think a good piece of art has to have a residue that cannot be explained. There are many works that have been inexplicable for a while, and then became explicable. These then disappear: they are internalized socially. The inexplicable is what we call mystery—the unknown that remains there, and that presents the challenge to keep working.

IB: What do you think is, and should be, the role of museums and art institutions today?

LC: Museums are defenders of the canon. They believe in the walls of the building and the material space they occupy. They do not think of the enclosure as an osmotic membrane that is both outside and inside at the same time. Museums are consumed by the idea that the more people that circulate through the building, the more important the institution is, therefore they may seek for more material space to accommodate more circulation. It becomes a vicious circle that basically deals with expanding the consumer base, rather than generating creativity among those who do not usually exercise it. A good museum for me––like a good church––enables the believer to work with heresies instead of forbidding heresy. A museum in particular should promote the possibility of heresies, the questioning of the canon. For this, the education department in a museum is crucial and should have the same rank the curatorial staff has. The function of the museum should not be to grow the number of visitors, but to help transform them. The institutional role should be educational, and not a training ground for taste.

IB: What do you mean by transforming the visitor?

LC: Make the visitor aware of their own activities. I believe in what I call a socialism of creation, to break the arbitrary monopoly of what we call artists. It is not about appreciating art, but rather about figuring out the conditions that generated the piece and made it inevitable and indispensable. The public should work with that, comparing their solutions with what is presented, to then decide which one is more effective. In terms of pedagogy, that is how I approach it. Art appreciation is a limited and consumerist approach. Basically it is a form of vandalism.