Something other than either: Pati Hill // Kunstverein Munich

by Francesco Tenaglia

“Working in a confined space with very circumscribed objects gave me an immense feeling

of freedom and childlike irresponsibility.”—Pati Hill, Letters to Jill

Born in Kentucky in 1921, polymath Pati Hill moved to New York as a teenager, and, not much later, to Paris in order to grow her modeling career; she worked as a mannequin for some of the most sought-after fashion magazines of the era. And it was precisely in France, although in the less cosmopolitan countryside, that her writing activity took off, first with the publication of a journal, The Pit and the Century Plant (1955), and debuting in fiction with The Nine Mile Circle (1957).1 Both were anticipations of a prolific, if sporadic, publishing activity that would span collections of poems, novels, and artists’ books.

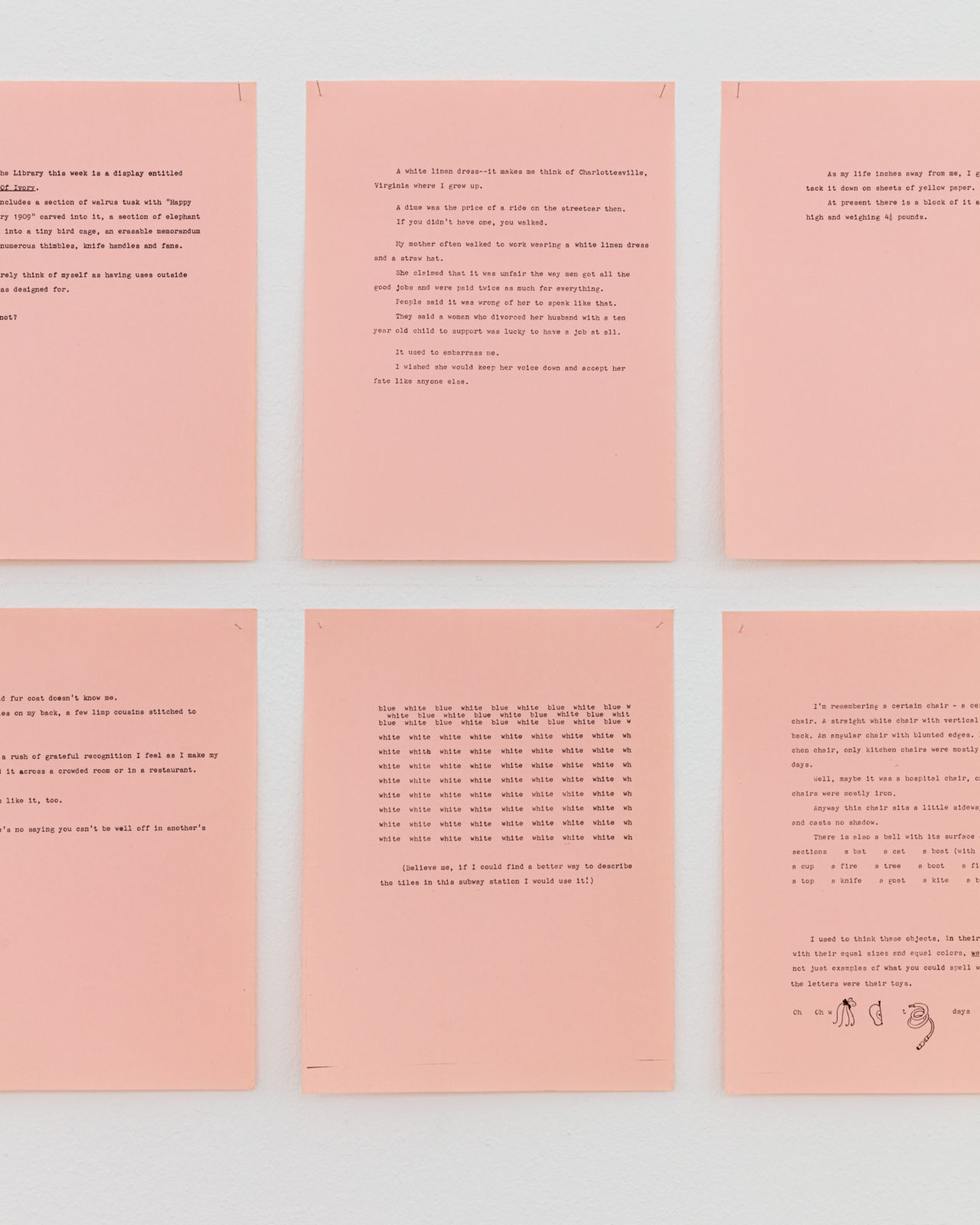

In the 1970s, Hill began experimenting with photocopiers as a means to produce images—a representative selection of her varied production is currently on display at Kunstverein Munich. Something other than either is Hill’s first European institutional exhibition, organized posthumously (Hill died in 2014) and on view through August 16, 2020. “We felt the responsibility to present different sides of her work to the public and as a platform to introduce her to museums that are cautious with lesser-known practices but may, at some point, organize a bigger show or acquire some of the works,” explains Kunstverein Munich’s newly appointed director, Maurin Dietrich.

The immaculate walls of the historical German institution showcase, among other works, a purple close-up of pants, captured front and back; an ironed shirt that reveals a recent pit stop at an upscale laundry; and a pair of elegant gloves designed to grip wrists with the aid of minute buttons, empty, one resting on the other. Each image is crystallized within the size, resolution, and chromatic limitations imposed by a machine conceived for quite other purposes. Hill’s shots portray, more frequently than not, ordinary objects relating to the domestic, evoking perhaps a canned, Proustian ennui or a conceptual, low-res version of the solution cards from the murder-mystery board game Clue.

Hill wrote about her cat in an ode to felines—particularly of the street-smart kind—published in the Paris Review in summer 1955: “I could tell that he was still more interested in what was going on in the street than anything else. It made me very unhappy because it gave me the idea of what it would be like to be a prisoner and so when I had the chance I gave him to some friends who lived in the suburbs, which he didn’t like either.” 2 The sense of feeling trapped recurs frequently in Hill’s production after 1962—the year when, after giving birth to her daughter Paola, she momentarily halted her writing practice to focus on housekeeping and raising a child. Her doubts and discomfort regarding motherhood were no secret, exposing the unwritten clauses in the marriage contract: she once called matrimony an invention of the devil and titled of one of her best-known books Slave Days: 29 Poems, 31 Photocopied Objects.3

The associations with secretarial labor implied by the use of a copy machine, in conjunction with her taste for objects gesturing toward the site of ‘home’ and its management, inevitably invite a reading of Hill’s practice as a feminist critique of assumed mythologies of art making (the heroic creator, sitting on the romanticism–modernism axis, advancing toward uncharted aesthetic territories, Olympically unconcerned with details of everyday life), traditional (read: patriarchal) gender roles more broadly, and the hierarchical regulation of conduct as functional to the maintenance and reproduction of the capitalist machine. This sensibility is profoundly summed up in Margaret Benston’s groundbreaking essay “The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation” (1969), which helped develop the framework for social reproduction theories in activism and academia in the decade that followed:

As an economic unit, the nuclear family is a valuable stabilizing force in capitalist society. Since the production which is done in the home is paid for by the husband-father’s earnings, his ability to withhold his labor from the market is much reduced. Even his flexibility in changing jobs is limited. The woman, denied an active place in the market, has little control over the conditions that govern her life. Her economic dependence is reflected in emotional dependence, passivity, and other typical female personality traits. She is conservative, fearful, supportive of the status quo. Furthermore, the structure of this family is such that it is an ideal consumption unit. . .Everyone in capitalist society is a consumer; the structure of the family simply means that it is particularly well suited to encourage consumption.4

As academic and author Kate Eichhorn observes in Adjusted Margin: Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century (2016), the advent and proliferation of affordable photocopying technology in the 1970s made the copier an essential tool for groups engaged in social activism—for instance queer rights and second wave feminism—and by music-centered niche subcultural groups. All shared similar dissemination tactics through the establishment of small presses, fanzines, handouts, and leaflets, and likewise had in common a punk, gritty aesthetic that became familiar visual jargon in urban landscapes internationally. 5 The xerographic affiliation with, and proximity to, underground and leftist culture popularized such techniques in visual arts. “Many copier artists are women, and some copy themselves exclusively. I don’t copy myself, but I modeled for years on account of the particular feeling of reality it gave me. The reality of an object, maybe. But it is more complex than that, as women who have done the same would tell you,” Hill commented obliquely, yet concisely, in her 1979 book Letters to Jill.6

It would be reductive, though, to state that Hill’s work exists only as an idiosyncratic visual rendering of individual and societal circumstances. Her artistic preoccupations embraced technique and materiality itself. In her hands, the photocopier’s very limitations—its technical constraints in terms of the size and style of its output—enabled a sophisticated postmodern reflection on commodities, replicas, and simulacra. Hill questions what could constitute a xerographic ‘language’ through various means—for instance injecting more ink than normal to increase contrast—to explore its expressive possibilities: her journey toward a distinctive plastic “expanded techniques” vocabulary for her beloved IBM II. More than once in her writings, she grasps for a word that could function for copy art as “photogenic” does for photography. For instance, an encounter with a dead swan on the beach leads to the immediate realization that “the feathers would copy well”; and while employing old publicity photos while working on the book Sweet Dreams on the Blue Train, she notes, “I have stopped using photos by known photographers not because I believe my temporary transformation of them is a desecration, but because a photocopy is not necessarily the best base for a good copy.”7 She even explained her long-term, Wagnerian (or one might say Herzogian) project of copying the whole Palace of Versailles as producing a new representational methodology for a subject documented to exhaustion by other means, such as painting and photography.

As an exhibition, while succeeding in accurately representing the practice of Pati Hill in its subtle articulations and in the various moments of the author’s artistic journey, Something other than either does not aspire to encyclopedism: with a light and agile character, the exhibition perhaps programmatically inaugurates and sets the tone of the near future of the institution “I didn’t work on this exhibition as a posthumous retrospective,” continues Dietrich “but more like a show of an artist who didn’t get the deserved chance to have a Kunstverein show at the right time. One guiding principle of my work here at the KM will be to dedicate part of the program to artists, groups, or collectives who deserved attention a while back, but were overlooked or marginalized because of race, gender, or class, and are now outside the canon.”8 The entire radius of the American artist’s personal and intimate grammar would probably remain elusive, if not ineffable, even in future desirable insights, permutations, or iterations: this first European institutional exhibition is a seductive invitation to learn its rudiments.

Pati Hill, Something other than either, runs at the Kunstverein Munich through August 16, 2020.

- Pati Hill, The Pit and the Century Plant (New York: Harper, 1955); Pati Hill, The Nine Mile Circle (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1957).

- Pati Hill, “Cats,” Paris Review, Issue 9, 1955.

- Pati Hill, Slave Days: 29 Poems, 31 Photocopied Objects (TKcity: Kornblee Gallery, 1975).

- Margaret Benston, “The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation,” Monthly Review, September 1969.

- Kate Eichhorn, Adjusted Margin: Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016).

- Pati Hill, Letters to Jill (New York: Kornblee, 1979).

- Hill, Letters to Jill.

- From a conversation between the author and Maurin Dietrich.