Sonics and Politics: Samson Young // Smart Museum of Art

by Elliat Albrecht

This summer has been a difficult one in Hong Kong. Sweltering, as summers always are in China, and fraught with rising political tensions. On June 16, more than two million people marched across Hong Kong island to protest a controversial anti-extradition bill that threatens to jeopardize the basic judicial rights and safety of citizens, and what is seen by many including the United Nations as excessive police violence against civilians. The afternoon prior, a man fell to his death from a luxury shopping mall roof while protesting the hated bill—one of six such protest-related fatalities as of mid-August. While the colossal crowd chanted slogans in Cantonese (“chit wui,” or “withdraw the bill; and “gai yau,” a colloquial term of encouragement translating literally to “add oil”), performers stationed under a bridge sang John Lennon songs in stirring harmonies. As demonstrators walking west neared the site of the fallen man’s death in Admiralty—by mid-day, heaped with hundreds of thousands of white flowers—a heavy hush fell over the masses. A silence that trapped air in millions of lungs, a silence that drew tears.

Hong Kong artist Samson Young’s practice is often situated at this loaded intersection between sonics and politics. Working with performance, drawings, animations, installation and (increasingly 3D-printed) sculptures, his works examine sound as a social and politically charged entity.

Elliat Albrecht: Your recent solo exhibition at Centre A in Vancouver, It’s a Heaven Over There—which included animation, historical documents, audio recordings and a neon-lit sculpture of a smoking fountain—drew on the history of Won Alexander Cumyow, the first person of Chinese descent born in Canada. How did this focus come about?

Samson Young: Tyler Russell, the former director at Centre A, took me around Vancouver’s Chinatown on our first research trip. We stumbled upon an object in the military history museum there that belonged to Won Alexander Cumyow, a key member of the Chinese Empire Reform Association, community leader, and claimed to be the first Chinese-Canadian born in Canada. We were surprised that anybody could actually make such a claim and wondered about whether the assertion could actually be verified. That was the beginning of a journey that took all sorts of turns and ended up somewhere else.

The exhibition took place in a former shopping mall in Chinatown—a neighborhood that has been continually threatened by outside interests since its establishment a century ago—and “stage[d] a double vision of global retrotopianism.”

The works that were featured in this exhibition were underpinned by three lines of thinking that started as being entirely separate, but then came together. It is probably more accurate to say that I forged a connection between these otherwise very separate things, and then tried to make sense out this juxtaposition. The first is the history of Cumyow. I was thinking about his relationship to the Chinese nation as a kind of “observer” from afar, and somebody who was able to maintain a somewhat romanticized image of the Chinese nation precisely because he did not live in China.

The second line of thinking is much broader and has to do with utopia as a political force. This is a part of a longer-term research project, which started when I visited Chicago in early 2018 and chanced upon some materials at the University of Chicago on the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair.

The third line of thinking has to do with the context of the exhibition, Centre A’s new space at the Sun Wah Mall, which to me looks very much like the kind of small neighborhood mall that I grew up with in Hong Kong in the 1980s. There was one right next to my parents’ old place in the North Point area of the city called “City Garden,” which was the former location for one of the most successful local department store in history: “Da Da Company” [Big Big Company.] Da Da Company went bankrupt in 1986, and the City Garden mall has since been taken over by several churches, where they co-exist with empty storefronts and barely-surviving small businesses. If you look hard enough, there are still traces of Da Da Company’s architecture in the City Garden mall today. So the exhibition mixed all these different threads and attempted to twist them together like a composition exercise—like in a song.

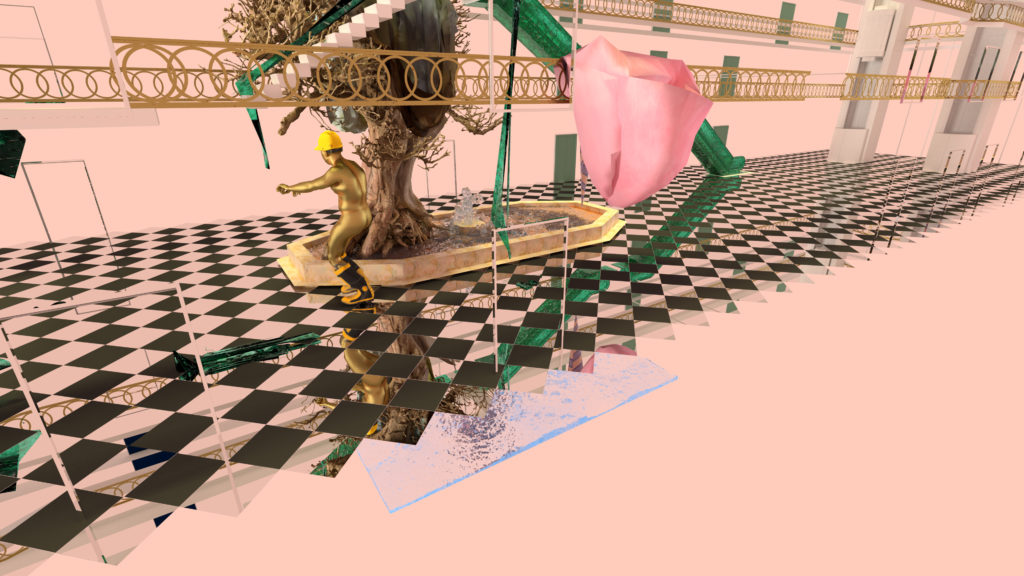

At the core of this show is an animated music video, Big Big Company (2019), which features the 3D model of Cumyow as a character who danced his way through a series of strange images and environments, to a sound track that is my version of My Favorite Things from The Sound of Music . The second component is a collection of drawings about notions of utopia, which were displayed alongside a set of photographs that were taken at the City Garden mall. The third and last component is the recording and documentation of interviews that I conducted inside of a truck, in the form of a mobile-marathon live broadcast in Hong Kong in December 2018. Entitled It’s a Heaven Over There (2019), the work is a 12-hour-long marathon of conversation on notions of utopia through the lenses of history, art, literature, cinema, politics, education, social activism, music, and international relations.

EA: You have said that you develop ideas through mental mindmaps. Though the various and divergent nodes connect for you, perhaps the viewer cannot draw every link in an exhibition. This reminds me of your description of the way the mind “fills in the gap” to imagine the totality of sounds one cannot comprehend—

SY: Yes, I would agree with that. When I make a show, often I am saying ‘here is absolutely everything that is going on in my head when I am in contact with these materials.’ I do not worry about how much of that gets through to the audience, or whether or not they connect.

EA: What can viewers expect at your upcoming solo exhibition at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago? Is the show related to other recent projects?

SY: The show at the Smart will feature a trilogy of animated music videos, all of which are related to utopia in some ways. In 2018, I started a conversation with the institution about a solo exhibition that would be in conversation with the University of Chicago library’s collection. I was drawn to the materials on the 1933 World’s Fair, which also took place in Chicago. At that point, I already had two other shows lined up—both at Edouard Malingue in Shanghai, and Centre A—so I decided to digest this rather large topic in smaller bites over three shows. In these three animations, the last of which will debut at the Smart, I am looking at aspirational thinking from different angles.

The 1933 World’s Fair carried the subtitle “A Century of Progress.” It was an interesting time for such an event. The Great Depression was well underway, and shit was about to hit the fan with the Second World War. It was also an era when all the different ideologies—from fascism, to communism, to capitalism— were still very much in play. Compare that with now, when nothing is in play anymore. We have truly reached the end of history, not in the sense that Francis Fukuyama had defined it, where capitalism is the end game, but with a failure of the imagination to envision a future that is better than now.

The third animation, which will be shown for the first time in Chicago, focuses on the World’s Fair. Part of the music video was shot at the ‘Houses of Tomorrow,’ which were built and shown for the first time at the 1933 fair, and have subsequently been preserved. The five houses are now part of the Indiana Dunes National Park.

EA: You use color abundantly—I am thinking of your sound drawings, neons, and brightly-painted walls in exhibitions like The Highway is like a Lion’s Mouth in Shanghai and One Hand Clapping (both 2018). Do you associate particular colors with sounds?

SY: In my installations and room settings, I like to use saturated colors and their playful child-like quality. But the matching of sound to color and shapes in my drawing is a whole other bag of things. The relationship there is more precise. I do not have synesthesia, but I do have a very strong and somewhat consistent sound to color imagination. C major is always a like transparent yellowish color to my ears.

EA: When working with choirs and bells, does the connotation of holiness appeal to you? How do you consider the effect of sounds while you are working?

SY: In some works, yes. For Whom the Bell Tolls (2015) makes reference to this history, and years ago I made a musical theater piece specifically about that too.

EA: You have said that composers are at the forefront of responding to technology. Do you consider forthcoming developments in surveillance, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence?

SY: Yes, I think that is true. There are all kinds of interesting projects floating around in the area of AI and music that are too numerous to mention, but I do think that the history of music is very much a history of technological development.

EA: I thought of you during the unfolding of the Jamal Khashoggi incident, particularly when Turkish officials announced they had audio evidence of his murder. Do you think of sound as dangerous or as a tool of resistance?

SY: Sound and music are dangerous precisely because they are a very potent tool of resistance. Music cuts right through the intellect and appeal to the emotions. But it plays both ways, right? For example, authoritarian governments frequently use the power of music in propaganda and in rituals.

EA: The use of 3D-printing has become more prevalent in your practice of late. How do you consider the relationship between these objects to the rest of the work? Do you consider them as sculptures?

SY: Sometimes they are sculptures, sometimes they are sets to a theatrical environment that I am trying to create, and not like super precious objects on their own. I like using 3D-printing because I am not a sculptor, but I know how to model stuff in a 3D programs. The process gives me a level of control, because there is only a small gap between my mouse sculpting the thing in the computer, and the actual physical printed object.

EA: You have called composing the tool you use to organize yourself. Does this extend to aspects of your life, outside of artmaking?

SY: I wish. I have come to realize as I grow older that my art is really the only place where I can achieve a satisfactory level of control of form. And art is a safe space to let my OCD self go crazy—nobody is going to die of a terrible accident if I played around with imposing new forms in my art.

I have always thought that the negotiation between form and content in art mirrors the struggle between idealism and realism in life. In a musical composition, form is what keeps everything together, a temporal structure that is beautiful on its own: the ideal vision of the thing, the blueprint of the thing. But the form itself does not make the work. Content is what you fill the form with, and also all the whimsical craziness that happens in the moment of composing, which sometimes wants to defy the form—you then have to make decisions about whether the form or the content is going to win in any specific musical moment. Then there is also the kind of form that is emergent, and that comes into being organically through acts of improvisation.

These organic musical forms are a bit hit and miss—but, when they do work, it is usually something that is so out of this world and so complicated that it is impossible to plot in advance.

EA: What makes a system of notation attractive or interesting to you?

SY: I like order, but I also like seeing what people do to defy that sense of order, or use that structure to propose their own alternate system within a system.

EA: I am sure you also read about how US diplomats in Cuba became suddenly sick (with symptoms mimicking brain injuries) after hearing persistent buzzing noises. While American officials once thought it was sonic warfare, experts now think the sound was simply “lovelorn crickets.” Your work suggests that you appreciate the absurd.

SY: The world is absurd. But sonic weapons are a real thing, and always have been.

EA: If you were not an artist—or a composer—what would you be?

SY: Probably a writer.

Samson Young (b. 1979) was trained formally as a composer before he became one of Hong Kong’s most internationally exhibited artists. His multimedia presentation Songs for Disaster Relief at the 2017 Venice Biennale was entered around the trope of 1980s “charity singles” and their often tone-deaf implications. Earlier works, such as the video Muted Situation #1: Muted String Quartet (2014), saw the artist direct musicians to play through the entirety of a composition without applying full pressure to their instruments, leaving only the sounds of the performers’ breath and fingers along the finger boards. A culmination of a year-long residency, Young’s first US solo museum exhibition at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago and is centered around the idea of utopia.

Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will you Buy of Me? at the Smart Museum of Art ran through December 29, 2019.