Stateless: Views of Global Migration

by Noah Hanna

I am acutely cognizant of the repetition in which the discourse of artistic practice finds itself negotiating the infringed humanity of migrants and refugees. In September 2017, THE SEEN featured the work of Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili, whose minimalist and celestial topographies mapped migration as a solitary resistance towards traditional nationstates. A year later for this publication, Hiba Ali wrote on artist collective Postcommodity’s interrogation of the architectural ideologies of colonialism in the US border region. Yet, continuous artistic reexamination does not seem superfluous. As of June 2018, the United Nations estimates there are some 68.5 million forcibly displaced people. Paired with the confluence of abhorrent hostility toward human rights by so many in power across the globe, the actions of interventionist artists and collaborators must serve to further our discourse surrounding the perpetual complexities of global migration. Such work engages a precarious balance between the conceptual ascription of territories, the movement of foreign bodies en masse, and the individual within systemic anonymity. In Stateless: Views of Global Migration, The Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) at Columbia College Chicago joins in a narrative that remains timeless, unresolved, nameless, and stateless.

Adopting a variety of methodologies, the artists included within this exhibition make use of photography and video as a means of paying respect to those entrapped within the status of statelessness. However, there can be inherent pitfalls when attempting to humanize a subject that remains broadly unknown to viewers. Push too softly, and the concern seems disingenuous; overexert, and you risk diverting attention away from the subject. Achieving equilibrium requires an understanding of the self equal to the lives of those documented. The artists in this show weave, at times literally, the complex narratives of these stateless subjects to explore the personal traumas and considerations of an uncertain future for refugees around the world.

For many of these artists, statelessness is the ascription they must bear. The woven tapestries and paintings of Fidencio Fifield-Perez unfurl as a personal topography, constructed laboriously in an effort to bridge the many landmasses the artist has crossed as a DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipient. The ephemera of university degrees and United States residency applications—all needed to provide evidence of the artist’s legal status—document a journey under statelessness. The envelopes that once housed these documents now serve as canvases for beautifully rendered plants; they speak as much to a sense of home as they do to continued growth. While Fifield-Perez examines his life in the US and his desire to one day achieve permanence, other artists document the detritus of migration. Hiwa K’s and Bissane Al Charif’s deeply affecting works offer glimpses into the hopelessness and suffering so many refugees endure, providing clarity in lieu of consolation.

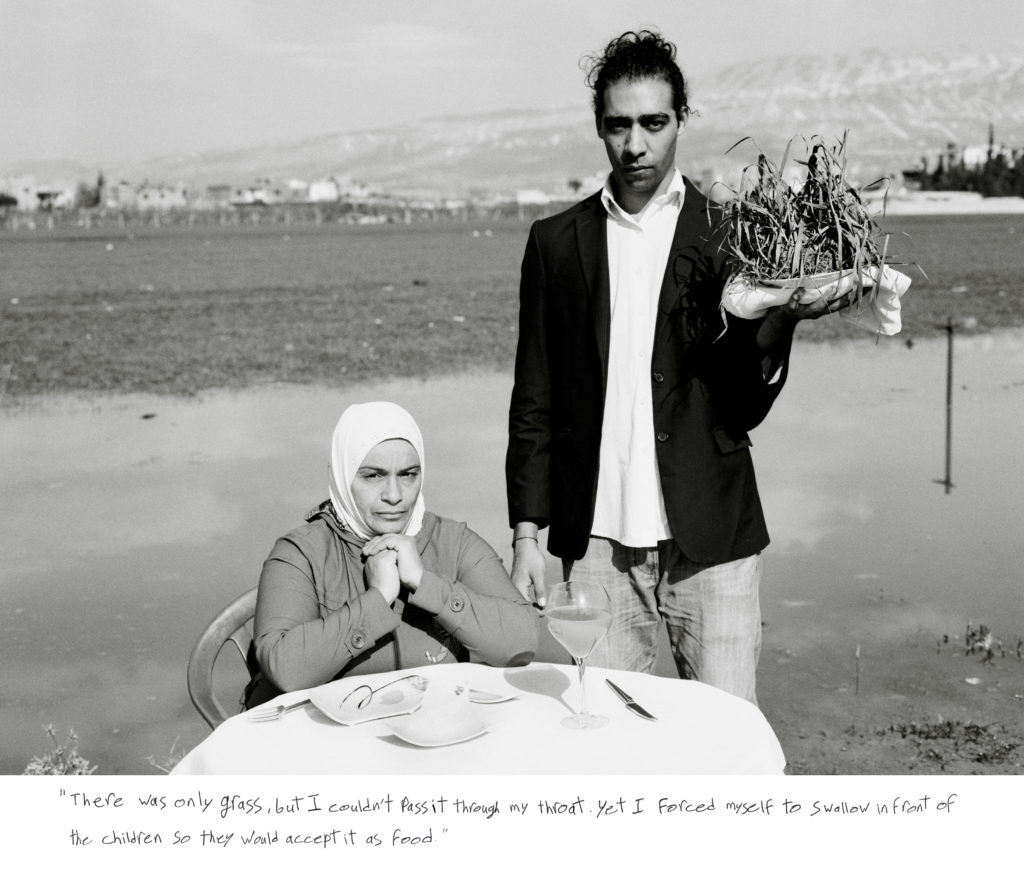

In more photojournalistic projects, such as Daniel Castro Garcia’s images of the young refugee boys who he mentors in Italy, and Omar Imam’s Live, Long, Refugee, project which records life within Lebanese refugee camps, the works serve as an honest platform wherein the marginalized can exert their voices above the noise and statistics of contemporary communication networks. In Shimon Attie’s The Crossing (2017), Syrian refugees are given center stage to reenact the risk they only recently undertook to arrive in Europe, this time upon a roulette wheel.

The multitude of perspectives surrounding statelessness these artists present creates a dichotomy of resolution. During the exhibition’s symposium, a clear divide emerged between artists Fifield-Perez and Hiwa K concerning whether the refugee crisis could ever be resolved. Fifield-Perez emphasized that while protections such as DACA are feeble at best, opportunities and resources remain to aid refugees, and art remains a powerful tool to break stereotypes and encourage greater representation. In contrast, Hiwa K expressed a more pessimistic vision of the future, indicating that he would be abandoning his artistic practice in favor of becoming a nurse, preparing for the inevitable violence to come.

This exchange was critical towards the discourse of migration within artistic practice. The potential ineffectiveness of art to alleviate suffering creates an unpalatable reality for so many who have devoted their lives to it. Yet this is where we reside. Through images, whether as art or media, we are faced with the need to recognize those in pain, but are not always prepared to upend the structures that enable it. A subject’s visual representation, though poignant, is not equitable to its existence; and the prospect of alignment between these poles remains an enigma. Aside from the threats of violence and treacherous seas, refugees find themselves affixed between geopolitical indifference and hopelessness. As viewers, we acknowledge the presence of suffering, but lack the resources to distinguish humanity from the body. We document faces and casualties, but art must strive for more.

In conversation with the MoCP’s Executive Director and Curator Natasha Egan, she emphasized the importance of education and visibility for this exhibition. For the multitude of Chicago Public School students who explored the show with us, many of whom may face the same battles as these artists, works like these serve to embolden as much as educate. The MoCP’s collaboration with organizations—such as The Heartland Alliance, The Karam Foundation, and The National Immigrant Justice Center, among others—provide awareness to the many people who work selflessly for those in need. It is not that art should be abandoned, but rather that it should be expanded. Hiwa K encouraged viewers to begin to think with their hearts, and for the sake of so many around the world, we must heed his advice.

Stateless: Views of Global Migration ran at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from January 24—March 31, 2019.