A Period of (Economic) Optimism: Terence Gower // Havana Case Study

by Joel Kuennen

Just last year, President Barack Obama visited Cuba, becoming the first US president to do so in over eighty years. “I have come here to bury the last remnant of the Cold War in the Americas.”1 The image of such a visit, of America’s first black president visiting a nation that ostensibly overthrew its white colonial masters in favor of an altruistic attempt at post-colonial governance, was heartening. It marked an attempt to introduce openness, to engender development not by force or coercion, but through partnership. It said, in part, we took different paths but we are here now, together—projecting an image of the United States not as a withholding parent, but as a peer. It was a move of respect.

This parity in positioning is what Trump took issue with when he decided to renege on the thaw, calling it a “completely one-sided deal.” Though the US embassy in Havana remains open, the US and Cuba seem stuck again between projections of hyperbolic political polarities.

On the occasion of the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial, Neubauer Collegium Exhibitions has brought Terence Gower’s Havana Case Study to the University of Chicago campus. The second in Gower’s interrogations of the architectural arm of the US Diplomatic apparatus, Havana Case Study presents Gower’s unique approach to research and production. Through researching the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO), site visits to Havana, and research with the National Archives, Gower is able to track an evolving logic behind the United States’ physical presence in nations with whom it has a historically fraught relationship. From the plantation-esque Jeffersonian style during the height of US imperialism to the high modernism of Cold War-era US-as-protector-of-Democracy-bringer-of-freedom, the architecture of the United States’ embassies has been both a site of projection and contestation but always one of ideology.

Joel Kuennen:: Your upcoming show, Havana Case Study, will be on view this Fall at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society—can you give us a quick overview of the planned exhibition?

Terence Gower: Yes—we will be presenting all of the elements of the project, installed at different sites around the Collegium. The first showing of this work was at Simon Preston Gallery in New York, this past November/December—timed to open two days before the election—which we knew would have a major effect on the subject of the show: the US diplomatic presence in Cuba. For the Preston exhibition, I removed the interior walls within the gallery, so a viewer peering through the glass looks directly into its long oblong box. A huge rebar sculpture, entitled Balcony, which is twenty-seven feet long, was placed within the space, giving the feeling of a showcase that displayed a single object. The sculpture is a 1:1 three-dimensional drawing of the balcony of the US Embassy in Havana, done in 3/4-inch acid-etched rebar. For the Collegium installation, we are installing the sculpture outside on a raised terrace—it can be read as either a skeletal ruin, or a component of new construction. I like the idea of the piece displayed adjacent to the surface of a building—it could appear at once ready to be hoisted into place on the façade, or may have just come crashing down.

In many of my architecture and urbanism-related works, I offer the viewer a display of my research material—a table of documentation and photos. The Collegium show will mark the first presentation of the documentation table for this project, consisting of a narrow table that displays two layers of material: the first is a vast old-school vitrine, with a traditional display of documents relating to the 1953 US Embassy in Havana, designed to look like a small architectural exhibition from the late 1950s. The second is made up of more recent newspapers, books, magazines, and other material that tells the fascinating story of how the US Embassy building was used for propaganda purposes by both the US and Cuba since the two countries broke diplomatic relations in 1961 (recently restored, sort of).

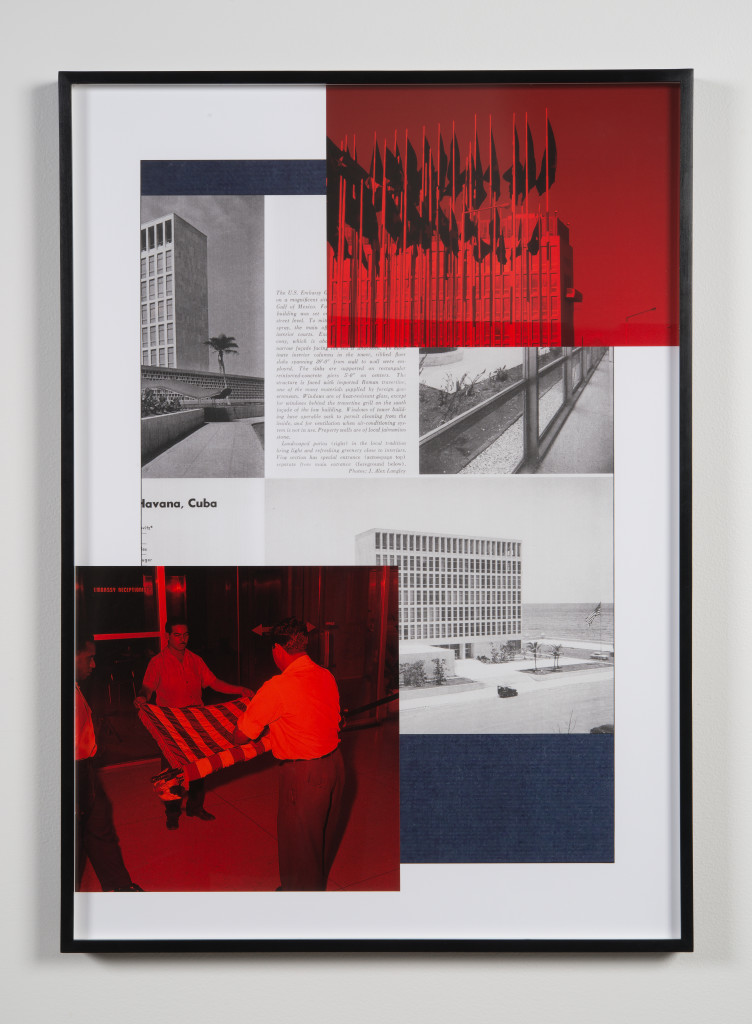

Additionally, a set of collages that play with this layering will also be on view [previously exhibited at Simon Preston], in addition to a few smaller sculptures titled Modules (one of which was shown in New York), based on the balcony form again, but this time some of the planes of the form are filled in with wickerwork. The piece illustrates the difficulty of generating architectural (or sculptural) form under the US-led embargo against Cuba, with its scarcity of materials. One of the materials you see everywhere is rebar, which used for everything and still manufactured in Cuba. In the countryside, I came across a lot of virtuoso work in woven vegetal matter, beautiful objects born of necessity.

JK: The embassy sites of your Havana and Baghdad projects are in different states of diplomacy. The US Embassy in Baghdad, Iraq, designed by Josep Lluís Sert, became a failed project—discarded half a century ago, and then relocated, rebuilt, and refortified in an act of colonial annexation during the latest Iraq War. The US Embassy in Havana, on the other hand, is now once again in a state of limbo after Trump backpedaled on Obama’s move to thaw relations. What qualities led you to choose Havana as the next project location and what kind of dialogue has developed for you between these two sites?

TG: I was drawn to the two sites for different reasons. My original idea, after researching the post-war US Embassy program and its emphasis on good modern architecture by the best architects, was a project about the whole program. However, the Sert project for Baghdad stood out for several reasons: one, it is a virtually unknown masterpiece that needed to be shown; two, it marked a very progressive new phase in the embassy-building project, where architects were required to visit the site to research the local culture and building technologies; and three, the utterly fucked up diplomatic scenario between the US and Iraq. The US had already withdrawn its diplomatic presence from Iraq in 1967, leaving Sert’s building in legal limbo. Then began the long breakdown between the two countries, regardless of the notorious Rumsfeld/Hussein handshake, leading to the very opposite of diplomatic relations: an illegal invasion and occupation of another country. This made it difficult for me to visit Sert’s building—everyone had advised against it—so, the research was done remotely.

For the Havana project, by contrast, I had good access to the building site through a senior contact, but Cuban archives were blocked to me as a foreigner, even with various invented affiliations. So, I did the political and architectural research in the US. The Havana Embassy was very attractive to me as the second embassy in the “modern” project of the State Department (the first was Rio de Janeiro, also designed by Max Abramovitz), with the contract awarded in the late 1940s. Abramovitz was heavily invested in government projects coming out of the war, where he was designing air force bases. But the UN project was a big factor in the selection of [Wallace] Harrison & Abramovitz for the first fully modern embassies. Interestingly, immediately after Havana, Abramovitz designed the highly secretive CIA headquarters in the unincorporated community of Langley, in Fairfax County, Virginia.

I naturally saw an interesting pattern developing in my series of great State Department architecture at sites of failed diplomacy. Tehran might be my next project, though less for the embassy building (which is a bland “government-style” from slightly before the construction project I have been studying) than the urban context, which is covered in a previous project of mine on Victor Gruen’s Tehran Comprehensive Plan, and the obvious fascination around the ultimate diplomatic meltdown: an embassy occupation. I think the US Embassy in former Saigon also merits study, as an architectural masterpiece that needs to be re-presented in a larger historical and aesthetic context, and not just a set piece for the Tet Offensive.

JK: The Baghdad Case Study work led to your creation of a mock-up of the original pyramidal Sert roof, whereas the Havana Case Study has led you to focus on its curious and controversial balcony. What drew you to the balcony?

TG: In each of my architecture-related projects, I draw a form (or series of forms) out of the research that best represents my argument. These are forms that work equally well abstractly as they do representationally. For me, the Sert ambassador’s house roof was the hinge for the Baghdad project, as it represented his attempt at dialogue with local cultural forms, and in turn, a reflection of the progressive function of the State Department (to which this series can be considered in homage to.) When I examined Sert’s roof in the plan, I saw the gridded domes of the bazaar or caravanserai, as well as the geometry of middle eastern marquetry, hence the sculpture’s fabrication in cedar wood.

The balcony in Havana was the most beautiful and sculptural form on the building by far (the bris-soleil is also pretty nice) and when I saw it, I remembered it had a slightly controversial history, from Jane Loeffler’s account in her book The Architecture of Diplomacy (my bible for this series).2 In opposition to Sert’s roof, the balcony is a symbol of American imperialism, even described by a State Department inspector as “Mussolini-style”. But it was also a symbol that was soon incorporated into the larger significance of the building, as property of the US government, standing like a sore thumb in the middle of enemy territory.

JK: When writing about your Baghdad Project in Walls and Windows Architektur und Ideologie, you began an essay with “nowhere is political ideology more wrapped up with architecture than in embassy design.” How do you equate architecture with what it was meant to convey ideologically?

TG: It is interesting that in the Baghdad Embassy project, my reading of the ambassador’s roof was very much in the realm of conjecture with a dash of artistic license. Whereas with the Havana balcony, it took three days of combing through ten years of State Department correspondence with all diplomatic posts (at the National Archives) to find the inspector’s report with the Mussolini statement—in other words, a text that actually proposes the meaning of the balcony as a kind of ideological red herring.

JK: Your case studies function as synthetic representations of archival research. When engaging with this type of practice, what is your leading conceit? What are you searching for with these palimpsestic representations? Is it an editorial activity, as seems the case with your focus on Sert’s roof, or is it indicative of a broader ideological framework? Or are you trying to argue a point? Do you view the goal of this activity as constructing an alternative representation of the historical?

TG: I would say I am arguing a point, but not too forcefully. I am presenting my research material with my own commentary to show the viewer how I form my argument, which is then expressed in either the sculpture or video work at the center of the installation. The documentation is carefully curated into the table installations, but it is still documentation, and is open to the viewer’s own interpretation. This is part of communicating clearly, not obfuscating, and is perhaps even an act of generosity toward the viewer, though some viewers may find all that documentation a little daunting. However, the sculptural elements are also designed to offer other points of entry into the project. The presentation of the research also serves another purpose: it is an index of the (conceptual) labor that was invested in the work.

A few years back, I did a public discussion with Claire Bishop at the School of Visual Arts Theatre in New York that addressed exactly this point; the function of archival presentation in art practice.

As you know, artists have been incorporating whole disciplines and practices into their own for some time—I see this as part of the legacy of Duchamp: from objet trouvé, to pictures generation, to relational aesthetics, with lots of other steps in between, of course. In my own case, I have appropriated the techniques of the architect, essayist, cultural historian (to name just three) as a tool to process my subject matter. As far as an alternate representation of the historical, yes—I am trying to draw out alternative narratives from the material. One of my main goals in working with historical material is to look for progressive models from the past, especially in the post-war period in the US, a period of (economic) optimism, but also the start of the Cold War and the advent of McCarthyism. The embassy building program interested me for exactly this reason, as a progressive US government project that put good design in the service of international dialogue: a model we can continue to learn from.

Terence Gower was born in British Columbia, Canada. He studied at Emily Carr College, spent the early years of his practice in Vancouver, Cologne, and Mexico City and has continued to show widely internationally. He has been based in New York City since 1995 where he has shown at PS1, New Museum, Queens Museum, and many commercial and non-profit galleries. Internationally he has shown recently at Institut d’Art Contemporain Villurbaine, Lyon; MACBA, Barcelona; Tensta Konsthal, Stockholm; Museo Tamayo, Mexico City; MAC, Santiago, Chile; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin; MUSAC, León, Spain; and Au¬dain Gallery, Vancouver.