The Allure of Matter: Material Art From China // The Smart Museum of Art and Wrightwood 659

by Natalie Hegert

February 21, 2020. The call starts with small talk. Wu Hung is in Princeton, NJ. Orianna Cacchione is in Chicago, IL. Natalie Hegert is in Lubbock, TX. It is a sunny day for all three of us. There are flowers starting to bloom in Princeton. We are hoping for spring to finally arrive.

On that day, just 34 people had tested positive for the novel coronavirus in the United States. Passengers from the Diamond Princess cruise ship were disembarking. And a top economic adviser for the Trump administration said there was “barely any impact” on the US economy.

One month later, following the stay-at-home order from Governor Pritzker in Illinois, on March 21, the Smart Museum and Wrightwood 659 closed their doors. The Allure of Matter, an exhibition of contemporary Chinese art over five years in the making, is now closed from public view.

Of course, the museum closures and postponements and cancellations are sad. Sad to think we cannot now go out to experience this exhibition in person, which, in its scale and scope, must have been magnificent to see. One of the images that will always stay with me from this exhibition is a photograph of He Xiangyu’s splattered and stained kitchen, where he worked alone for six months to boil down his first ton of Coca-Cola (A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, 2009). In a video that is included on the exhibition’s website, the artist says that in that act he was “reminded of the powerlessness of the individual in China.” When faced with vast quantities of anything, that which is beyond human comprehension—the number of stars in the sky, the enormity of a mountain, the global supply and demand of Coca-Cola, the spread of a pandemic—you will inevitably feel small in comparison. “I wanted to repeat this powerlessness,” He says, which he did, with a small team of workers and 127 tons of Coca-Cola. In He’s action, we find a literal and symbolic alchemy: a transformation of a commodity and brand into a unrecognizable substance, a different kind of material that then becomes art. He shows us that when you boil it all down, the powerlessness you feel can be transformed into something else.

When I spoke with the curators that day in February—in preparation for the printing of this piece for THE SEEN Issue 10, which would also be postponed due to the virus—we did not yet know the scale and scope of the threat of COVID-19. We talked about the particular challenges of installing an exhibition where none of the artists could travel and be on site. But our conversation also highlighted the possibilities of remote cooperation: with the curators, artists, art handlers, and technicians talking via WeChat and transmitting photographs halfway across the world; and also for us, in Princeton, Chicago, and Lubbock, to come together via conference call to discuss an exhibition that the interviewer had only experienced online, through the extraordinary compilation of text, images, artist interviews, and videos available on The Allure of Matter website. With so much uncertainly, one thing remains clear: in this crisis, we are learning what we can accomplish—together, in isolation, and in virtual space.

Natalie Hegert: I wanted to start with the seed for this curatorial endeavor—did the exhibition stem mostly from your research?

Wu Hung: Actually, the inspiration came from a number of directions. One came from my research, another came from the museum. About five years ago, the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago was approached with the idea of organizing a large-scale exhibition on contemporary Chinese art. The Smart had the resources to organize and promote such an exhibition, and deeply understands this work—beginning in the 1990s, the museum organized a series of contemporary Chinese exhibitions. While I am primarily a Professor in the Department of Art History, I also act as an Adjunct Curator at the Smart, and the museum asked me if I had any ideas for this exhibition.

I had been looking at these artists in my research, in contemporary Chinese art and contemporary art in general, for quite a long time. I have always been thinking about a new angle, a new concept, and trying to discover some new themes. The opportunity of an exhibition and my research together allowed me to come up with this concept of ‘material art.’

Orianna Cacchione: I want to underscore that Wu Hung, and the Smart by extension, have truly been leaders in the field of exhibiting contemporary Chinese art—testing the limits of how it is exhibited in the United States. This dates back now twenty-one years to Wu Hung’s first exhibition at the museum, Transience: Chinese Experimental Art at the End of the Twentieth Century, in 1999. Nonetheless, what I think is really important about The Allure of Matter is that it radically proposes new ways of exhibiting contemporary Chinese art—namely, a thematic drive. In this way, thinking of contemporary Chinese art through the lens of materiality becomes very innovative.

NH: As opposed to exhibitions that are just generally contemporary Chinese art?

OC: Right, such as historical surveys.

WH: We have seen quite a few of these surveys at institutions across the US. Sometimes they emphasize historical or political themes. China is always, insistently taken as an “other space.” Of course, in China there’s a different history, both politically and artistically. There is nothing wrong with survey exhibitions, but I do not feel that there is only one way to approach non-Western art. We can find new ways to see it. In The Allure of Matter, for example, we wanted to present these artists in a way that is relatable to an American audience. Through the works included in the exhibition, viewers can discover the artists, their lives, their inspiration, their materials, and how their experiences are different. From there, if viewers want to understand the social experience in China, that is totally fine. But we want the artworks to primarily speak for themselves. So in this exhibition, we try to eliminate restrictions for interpretations. Everyone can see that these works are clearly a part of contemporary art in general, and are not of a niche style exclusive to China. The works presented across the galleries are very diverse; these artists looked to an array of inspirations and represent multiple generations, having grown up in the 1980s, ‘90s, or later.

OC: The exhibition attempts to foreground the art, not the artists’ Chinese identity. This is a very unique aspect of the exhibition, which makes it different from other [Western] exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art.

NH: So, looking at some of the images of the installation, it looks like there is some kind of magic involved in installing some of these huge works—let alone packing and traveling them from institution to institution as the exhibition was originally intended to move. I am looking at Xu Bing’s 1st Class (2011), in which thousands of cigarettes are arranged to look like a tiger skin rug. Do you have any anecdotes about installing these works? Are any of these that look really complex, surprisingly easy to install, or vice versa?

OC: If they look difficult to install, that is because they were. Even some of the works that seem the simplest to install were quite demanding. The sheer scale of many of the works becomes a challenge for American museums and exhibition spaces. I frequently debate the size and scales of artworks that can be shown at the Smart with artists and galleries in China. Often I find myself saying, “It’s just too big, we cannot even fit it in the galleries!” Trying to deal with the differences in scale between the gallery spaces in China, where many of the works in the show were originally made, and spaces in Chicago and throughout the US has been interesting to say the least. But it has been fascinating to see the sheer amount of labor that has gone into the installation across the two venues, and the ways that each of the different installation teams came together.

WH: Right, labor is quite meaningful for several of the works – the idea of collective workmanship. For example, Zhang Huan uses ashes to make his paintings and sculptures. The artist collects ashes from incense burnt in Buddhist temples, where the ash was left by thousands of worshippers. This becomes a meaningful part of the work. For other works, many people have to participate in the labor of making the work, for example Zhu Jinshi’s Wave of Material, the big work made of paper that is on view at Wrightwood 659. For these artists, these collective activities were a very important aspect.

Another thing that made installing these works especially challenging is the fragility of some of these materials, like silk or paper. The artists in The Allure of Matter really emphasize the qualities of the physical materials.

OC: Process plays an important role in all of these artworks. In addition to the collective labor that goes into making these works, their materials undergo significant transformations.

NH: I am reminded of the paper installation by Zhu Jinshi, Wave of Materials (2007/2020), where each piece of paper had to be folded individually. It seems like it is very tedious and repetitious, this kind of process.

OC: Instead of tedious, repetitious—I would say meditative.

WH: The paper itself, it is very soft, fragile. It wrinkles. Each of the 8,000 sheets of paper that makes up Wave of Materials was crumpled by hand according to Zhu Jinshi’s specifications. The process becomes spiritual—it is not just a mechanical folding of paper. There is human touch, and even human body’s temperature changes these materials. It is no longer raw material. The process becomes part of the product.

NH: I find the different qualities of materials, between each of the artists and their practices and what those types of materials point to, interesting—in the sense that some of the artists deal with materials that have a long-standing traditions of use in China, such as silk and xuan paper. But then on the other hand there are artists like He Xiangyu, who is boiling tons of Coca-Cola (A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, 2009), which is just amazing. He’s use of that particular material touches on industry, commerce, trade, the image of a brand. There is so much that is contained in that one material; it has a critique embedded within it.

WH: That note on globalization and commercialization is more recent to Chinese history, say after the 1990s. He Xiangyu is a younger artist, and he is more open to this kind of phenomena. Other materials across the exhibition have a different direction—they can be very personal, very intimate. There is a beautiful work by Lin Tianmiao, Day-Dreamer (2000), where she uses cotton strings to create an image that is entirely based on her memory of the past. Through this great range of materials—from pure paper to hard cement, concrete, plastic, etc.—one thing we hope to emphasize is that there is not just one kind of material that carries broad applications for these artists, but many kinds.

OC: Exactly—each artist is selecting each material very deliberately. The material choice is both significant and intentional.

WH: There are quite a few artists who have spent many years working with their chosen material(s). They have developed a significant personal relationship with the material. We hope to touch upon the very different contexts in which the artists engage, from practices like urban renewal to connotations of gunpowder and hair.

NH: Why do you think so many artists tended to deal with mass quantities of material?

WH: It is interesting—we just talked about these ideas of collective workmanship. For example, with Xu Bing’s 1st Class and Tobacco Project (2011), when this work was first installed at the Shanghai Gallery of Art, I was the curator of that show as well. We hired a whole team of workers to spend a week exclusively installing this piece. Cigarettes are produced in massive quantities, and there they were in the hands of the workers; it was almost like a performance.

The space that an artist is given to work with becomes an important factor. Yet, while some works are quite huge, like Gu Wenda’s hair temple, others are small and personal. Chen Zhen’s Crystal Landscape of Inner Body (2000) is about his own life. Again, I feel there are two different approaches to space at play in this exhibition; one artist will occupy a lot of space but another will have a small, personal work.

NH: One of the works that is really interesting is Gu Dexin’s plastic installation, Untitled (1989), which he started working on while he was working at a factory. The exhibition guide says he was one of the first artists to use unconventional materials in China. I was going to mention that this work was also in the very famous show, Les Magiciens de la Terre, in 1989 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. This work has a very interesting history, and is on loan from the Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon; so then it had to be shipped from Lyon to Chicago. What was it like to work with this installation? Is it the earliest work in the show?

OC: Yes—it is the earliest work in the show, though it is not the earliest example of material art. Gu Dexin was working with plastic throughout the 1980s; Cai Guo-Qiang’s earliest experiments with gunpowder happened in the late 1980s; and Huang Yong Ping’s book washing happened in the mid 1980s. Installing Untitled has been quite interesting because Gu Dexin has since left the artworld—he rejected working within the confines of the art market and the gallery-commodified art system. In 2008 he stopped working, and now he refuses to talk about his artworks. Trying to understand how to install that piece became a problem to solve. We worked with Sara Moy, a conservator in Chicago to study installation images of the work and develop our own method to install it in the absence of any instructions from the artist. It was like a puzzle, trying to have our installation match the original exhibited at the Magiciens de la Terre exhibition.

WH: Personally, I am so happy that we can bring this work to Chicago, to the US, because this work was not well known. Gu Dexin is quite a famous artist despite the fact that his major works have almost all disappeared due to the ephemeral types of materials he used. Initially we did not know a lot about this piece, but through an early Chinese critic, we learned that this piece may have been in France. Orianna did a lot of work reaching out to rediscover Untitled. So now we are able to install it and bring it to many, many people, which is something I am very proud of.

OC: I think this is a pivotal piece in Gu Dexin’s practice because it marked his transition from working on a very small, intimate scale to thinking about the possibility of plastic for installations. Almost all of his plastic pieces in the 1990s, many of which were shown in exhibitions throughout Europe, grew in scale and now have been lost or destroyed.

WH: There was a big show organized at the Guggenheim in 2018, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, where they also presented plastic works by Gu Dexin. But at that time they could not find some of the bigger works, so the work they showed was relatively small—the installation took up much less space than this one.

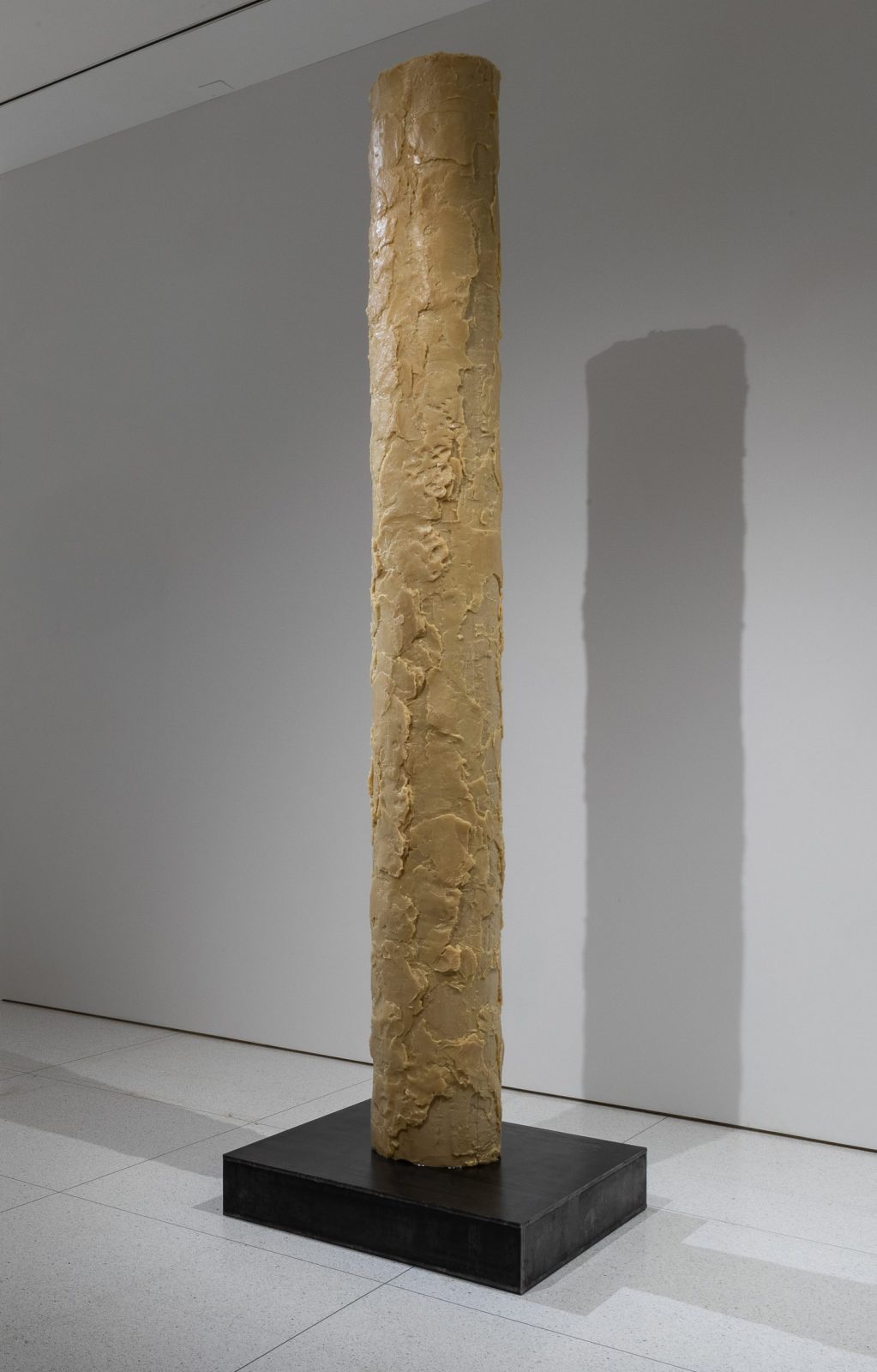

NH: Another interesting work that probably has an interesting history is Civilization Pillar (2001/2019) by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, which was originally produced in 2001 and commissioned again by the Smart Museum. What led you to commission a new version of this work, and were there any issues that arose with redoing this?

OC: This work is, for me, one of the most important examples of material art in the exhibition. The radical transformation of human fat, purifying and solidifying it with wax, acids, and vaseline is quite fantastic. The resulting work is aesthetically beautiful and striking, but also so minimalist. The material defines both the meaning and the significance of the work; for the artists, fat embodies the excesses of contemporary civilization. Civilization Pillar (2001/2019) was one of the pieces that, when I started working on the exhibition, I immediately thought of how crucial this artwork is to broadly conceptualizing the themes of the exhibition.

NH: Finally, I did want to ask about the unfortunate outbreak of the coronavirus, and how this may have affected the installation and traveling possibilities of the artists. Did this negatively affect the show? How did you deal with that?

OC: It did; it impacted the exhibition quite a lot, in the sense that we were unable to bring any of the artists that we had invited for the opening to Chicago. Three artists who were meant to come and oversee the installation of their works were also unable to join us.

NH: So how did you work around that, with the artists being unable to oversee the installation?

OC: A lot of conversations and photographic exchanges via WeChat, really. It was a lot of sending images and getting an enthusiastic thumbs-up or images of drawings and suggestions. It was not an ideal situation, but we worked around it. As far as I know all of the artists are very happy with how their works look.

WH: We remain hopeful that before the show ends in Chicago they can come here, maybe we can organize a panel or conversation. I do not see a major negative impact on the show, [despite] thinking about a terrible situation. Because all of the pieces were realized and we have been in constant communication with the artists—with the help of digital communication and the internet. They can literally watch the work being installed and make suggestions. That makes things a bit easier, although they could not physically be here.

While Allure of Matter is currently closed to the public, aspects of the exhibition, including installation images and interviews with the artists may be found at https://theallureofmatter.org.