The Artist As Frankenstein

by Elliot Mickleburgh

Alex Da Corte: Slow Graffitti (2017) // Jørgen Leth: The Perfect Human (1968)

“I double back to the moonlit entrance that leads to the open air of the cliffs, the funicular cars. When I find Magreb, I’ll beg her to tell me what she dreams up here. I’ll tell her my waking dreams in the lemon grove: The mortal men and women floating serenely by in balloons freighted with the ballast of their deaths. Millions of balloons ride over a wide ocean, lives darkening the sky. Death is a dense powder cinched inside tiny sandbags, and in the dream I am given to understand that instead of a sandbag I have Magreb“—Karen Russell, Vampires in the Lemon Grove1

Some of the most arresting moments in any entry into the horror genre are those tiny terrors in which the consistency of the world begins to flicker—even if only slightly—as if in a dream. These are the inchoate warnings that something is trembling in the (heretofore) steadfast laws of nature; something is buckling under the emergent forces of the paranormal. A cold skepticism multiplies in these moments, stimulating the consumer horror with a pathological fear of the direction through which a narrative could unfold. The quotidian ‘real’ has been issued a death threat from beyond the veil, but the monster has yet to make a significant insurrection into the world of the living—has yet to fulfill their sinister guarantee: that reality as we know it will be violated and reconfigured.

Across sequels, textual adaptations, action figures, board games, theme park rollercoasters, and the many other content mutations that compose horror as a form, glimpses of the genre last but only a moment before developing into something truly horrible. Fears are confirmed and validated only when the boogeyman finally jumps from the closet. It could be said that the agony felt under the duress of such unconcealed evil becomes something like the consequence of having intuited the same menacing power’s presence while it still subsided in an unevenly distributed disguise.

In an essay on horror’s sibling genre, science fiction, philosopher Quentin Meillassoux contemplates the narrative flow of causal relationships in such fanciful and eccentric tales. The father of speculative materialism praises this popular genre for its propensity to dissolve the persistence of natural law by imagining futures in which objects are known to travel faster than light and matter is transported across the universe at the press of a button. The previously described lapse from anticipatory terror into a fully realized horror rhymes conceptually with what Meillassoux then identifies as a flaw in most Sci-Fi works, namely the genre’s tendency to populate its confabulated worlds with characters for whom the machinations of supposedly impossible technologies are perfectly cogent, all too reasonable. If the regulatory function of the natural sciences is momentarily lifted in these fictional realities, triggering a spasmodic release of nothing so much as pure radical contingency, it seems suspicious that every inhabitant of said narrative should have such a detailed understanding of the chaos surrounding them.2

In a similar fashion, the prohibitions inscribed upon the world by natural law are disfigured when a monster lurks in the shadows and obliterated when they fully emerge to wreak havoc on peaceful townspeople. But have you ever noticed how the villains of the horror genre almost always seem to impose a monstrous will that is just as insistent as the normalcy that has been abrogated by their very presence? Even in the vilest transgression of sufficient reason, a bizarre but appreciably robust system of determination is ushered in to replace the more familiar causality that has been devastated by the monster.

Since this martial form of order already submits to rationalization, we might as well give it a name, too: supernatural law.

While Meillassoux would likely express disdain for supernatural law, it is perhaps not a coincidence that the horror genre so frequently places unearthly villains in positions of orderly power. As the writer Charlie Fox observes, the bildungsroman of a monster is often a most cautionary tale, a narrative injunction against regimes of ethical corruption. To function efficiently as a symbolic deterrent, the monster must assume a vantage of control, demonstrating the consequences of a depraved and immoral will. The horror narrative does so by letting evil momentarily ascend to this position from which it can reconfigure the world via artistry’s inventive instruments.

Much of Fox’s 2017 essay anthology This Young Monster carves out sympathetic responses to these eponymous creatures in horror stories. Rather than analyzing vampires and anthropomorphic beasties as merely humans debased by wicked decisions, Fox commends the transformative potential of beings pulled into such cycles of paranormal metamorphosis. To feel ourselves beckoned by monstrous change is not so much the teleological pull towards some denouement prescribing moral conformity. It is more like a spooky echo of that period in every human life in which radical and haphazard transfiguration ravages the body and mind: adolescence. Becoming a monster, Fox informs us, is as disorienting as the unpredictable changes in physiology and psychochemistry that take place simply as a part of growing up.3

Since the genre of horror so frequently falls back on an emaciated repertoire of aesthetic and conceptual choices, it would indeed be far more productive to seek an example of transcendence from supernatural law within contemporary art. Of particular interest to this end is Alex Da Corte’s video work Slow Graffiti (2017). Developed as a component to the artist’s 2017 solo show at the Vienna Secession and re-exhibited in 2019 for a group show curated by Charlie Fox at the London gallery Sadie Coles HQ, Slow Graffiti presents as a shot-for-shot remake of Jørgen Leth’s experimental short film The Perfect Human (1968).

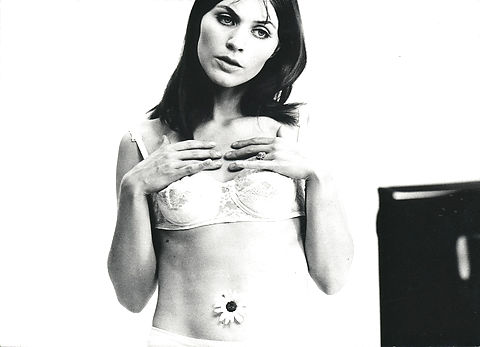

Leth’s original film depicts two figures going through the motions of rather prosaic gestures like smoking a pipe or getting dressed. The two performers, Claus Nissen and Majken Algren Nielsen, engage these activities in the sterile white void of a cycloramic sound stage, a setting used frequently during this time period for the production of commercial imagery. Nissen and Nielsen, both all too human, are transformed into living effigies of the old slogan better living through chemistry. And yet while both are delivered into the paradise shown to us by advertising, neither seem particularly happy living in the glorious and glamorous life that’s promised as a reward for the consumption of chemically mass-produced objects. In Slow Graffiti, Da Corte recreates this existential dissatisfaction but with a significant twist: in lieu of the original human subjects, Da Corte performs the gestures depicted in Leth’s film as a prosthetically concocted Boris Karloff, and Karloff’s most well-known Hollywood role, Frankenstein’s monster.

The London-born thespian William Henry Pratt, who would later assume a stage name with a more patently eastern European sonority, had been known to regard the gothic monster he played on the silver screen as his best friend. This simpatico relationship between performer and character becomes an additional framework within which Da Corte explores the laconic disappointment felt by those who wish for change only to loathe what they become, and it is indeed within this collision of Karloff and Frankenstein, of Leth and his players, that an emancipation from the articles of supernatural law can be located. For the eclectic personas in Slow Graffiti, the amalgams of Da Corte and Karloff, as well as Da Corte and Frankenstein, respectively propose transformations that promise regulated and contented existences, but each transformation in turn acts as a counterpoint for the other’s desire.

Early shots in the video show the composite of Da Corte and Karloff sensually fiddling with a number of objects, perhaps in hope that some magic spell will turn a tube of lipstick into a cigarette or a slice of deli meat into a makeup remover. Meanwhile, the composite of Da Corte and Frankenstein prepares a gaudy meal from a footlong Subway sandwich and haphazard splashes of orange soda while incanting the refrain sung softly by Nissen in the version of this scene in The Perfect Human:

Why is fortune so capricious?

Why is joy so quickly done?

Why did you leave me?

Why are you gone?

A conceptual version of the shot and counter-shot relationship is traced between these two scenes. The first composite character yearns for a transformation that will reconstitute the workaday as something provocatively weird. They long to feel even the faintest touch of the bizarre run its fingers across the margins of a world that has become trite in its subordination to rules. And as in almost every adaptation of Shelley’s literary magnum opus, the second composite pines for the social acceptance and requited love that seem to be possible only under the conditions of a world left unviolated by the monster’s will to power. And who among us could say that they have never felt these things before, and who has not felt them simultaneously?

The narrative in Slow Graffiti transcends the insistent moral regulation of supernatural law by positing transformation as a kind of contrapuntal relationship between modes of being, a flickering moiré formed from superimposing the needs of both the human and the monster. The latter being demonstrates to the former that to flee the banality of the phenomenal, one must resign to enjoy the pleasures of an unruly world completely alone. And in reverse, the former being demonstrates to the latter that assimilation into a world replete with companionship and love comes at the cost of having to compromise one’s idiosyncrasies, one’s very individuality, deformed though it may be. But to despair at this choice between one capricious misfortune over another—solitude from others, alienation from the self, or whatever other futures inspire knee-jerk antipathy—would be to glance over the benefit of inhabiting more permanently this volume of radical contingency. For transformation does the peculiar thing of telling two diametrically opposed moral tales at once. It declares the coexistence of multiplied deterministic systems, which is to say that it invents a contingent mode of being from the irrational gesture of intersecting oppositional states of necessity.

When the terror of transformation releases us from necessary moral behaviors, we can be empowered to speculate freely upon these resonances, the multiplied stakes of art and life itself.