The Chicago Imagists, Then and Now: In Conversation with Sarah Canright

by Barbara Purcell

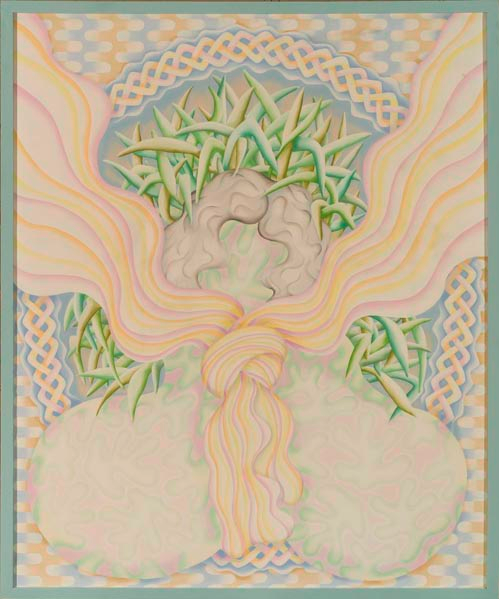

Artist Sarah Canright’s 50-year career has been impressive from the start, beginning in the late 1960s, when she began showing with the Chicago Imagists, a group who aesthetically defied New York’s minimalism and pop art scene with more colorful, figural artwork. A circle of friends who initially met at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), the Imagists put on a series of shows from 1966-1971, which won praise but also drew criticism from those who failed to recognize the serious and subversive nature veiled in their humorous surrealism. Now a longtime resident of Austin, Texas, where she continues to paint and teach at the University of Texas (UT Austin), Canright recalls those early days, largely defined by, as she says, good fortune, big challenges, and wonderful friendships.

Barbara Purcell: How important was the Hyde Park Art Center in the formation of the Chicago Imagists?

Sarah Canright: It was essential. Don Baum, who was the curator, and an artist himself, was truly one of a kind. He made quite a stir with our shows. Ruth Horwich, a wealthy collector who was also friendly with Don, was just as important in those early days. She was the first person to buy all of our works, which were dirt cheap—a few hundred dollars for a good sized painting. She often invited us to elegant dinner parties at her home, and introduced us to other major Chicago collectors.

BP: What was the biggest benefit, as well as the biggest challenge, to starting out in Chicago, as opposed to somewhere like New York?

SC: There was no gender divide in any of our groups. The Imagists were not the center of the universe—we were not getting massive critical attention, so nothing was dividing us the way the world divides “up people” before letting those divisions then set in. Many of us were wives and girlfriends, and even mothers. Suellen Rocca married young, and had two little kids, yet by the time she was a second-year undergraduate student, she was being recognized as extraordinary and influential.

It was only when I got to New York, where everything was so cold and inaccessible, did I realize we had been spoiled by those privileges which had befallen us at the Hyde Park Art Center. It was just very different, and it took me awhile, given my shyness, to get to know artists and make real friendships in New York City.

BP: The Imagists have a reputation of being less serious than other artists of the time, making art in a little bubble which lacked edge. Is that a fair assessment?

SC: We were just as involved politically as anyone else at the time—but it was not in the work. That was possibly the reason we were viewed as such. We were completely conscious of all that was happening in the late 1960s. Sure, we would have a good time when we all came together to organize our shows, but it is just plain erroneous to say we were not serious. Everyone in that era was trying to have a good time—not just us.

BP: How did the Imagists finally make their way into the New York art world?

SC: Phyllis Kind was the first big time, real money gallery owner in Chicago who showed interest in us. She was a huge presence, and she came right at the moment we were all beginning to sell. There were only a few serious galleries in Chicago and none of them showed Chicago art, but she selected various Imagists to show with her—including Jim Nutt and Roger Brown—and when she moved her gallery to NYC in the mid-70s, it was the city’s introduction to that art.

BP: You left Chicago—and the Chicago Imagists—behind and moved to New York City in the mid-70s. Can you talk about that transition? And the trajectory of your art since then?

SC: The Art Institute of Chicago used to put on these “American shows” every two years, which often only spotlighted what was happening in New York. The works of Dan Flavin, Robert Irwin, and Carl Andre beckoned me, and by the time I left Chicago, I was emptying the painting out—the image was being disintegrated. In New York I continued in the same reductive vein with a very pale palette. I remember seeing a Robert Ryman at the Museum of Modern Art, and I immediately thought: he is where I am going. But I had trouble finding gallery representation, so I began to reintroduce color and things really picked up in the early 80s for me.

BP: You and fellow Imagist Ed Flood were married by the time you moved to New York together. How did you navigate your art careers within the relationship?

SC: Edward showed at a gallery in the first couple years, but his work had also moved away from imagery—and he paid a far dearer price than I did, since he was and is considered a more serious Imagist. Chicago never forgave him. He had a show at Kind’s Chicago gallery a few years after our move to New York, and only one piece sold.

Circumstance had led us to New York. After losing our place in Chicago, we were offered a friend’s empty Manhattan apartment—all we had to do was cover gas and electric. There was lots of good fortune, but also lots of hardship early on. Money was tight, but Edward’s outlook was amazing. I remember once getting annoyed at him for covering our kitchen table with all sorts of random junk, and he simply told me he saw the possibilities in everything. We had different temperaments. I wanted to clean up the house and he wanted to fill up the house.

BP: You’ve been an art professor at UT Austin for many years: how are students different today compared to your time at SAIC?

SC: It used to be, no matter where you ended up, you began as a painter. We were committed painters and, and we absorbed those paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago, we talked about them and studied them. When I took a visiting artist job in Chicago in the ‘80s, I was appalled that students no longer hung around the museum.

Also, art students today also have nothing to react against—anything goes. In the ‘80s, artists reacted against the reductive language of minimalism, and in the ‘70s, the minimalists reacted against the excesses of expressionism. But if you were to walk around all the galleries in New York City right now, you would see multiple strains. So students do not have the same sense of extending a language or working against a language, and they are conscious of that—especially graduate students.

BP: Forty years went by without much mention of the Imagists, but in recent times there have been multiple exhibits here and abroad. What do you attribute this resurgence in interest to?

SC: When you have a major player like Jeff Koons bringing Ed Paschke’s work to Gagosian, people pay attention. Work that is coming from a person, and not just a strategic or theoretical point of view. Honestly, I think people are hungry right now for something that feels real.

Sarah Canright graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and began showing with the Chicago Imagists in the late 1960s. In 1972 she moved to New York City, eventually splitting her year between New York and Texas in the 1980s, and accepting a full-time teaching position at the University of Texas at Austin in the mid 1990s. She has won three National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship Grants and a New York State Council for the Arts Grant. She was included in the 1975 Whitney Biennial.