The Desire to Forget: Luc Tuymans // Palazzo Grassi

by Ruslana Lichtzier

The Palazzo Grassi casts a long cooling shadow upon the Venetian Grand Canal, which is otherwise trounced by a blinding sun and Disneyworld-like waves of tourists. The palace is a swansong of the Venetian Republic: it is the last residential building to be erected before the state collapse in 1797. Built in 1748 in Venetian-Classical style, the palace was originally designed as a monumental exhibit of the Grassi family’s power,1 with forty rooms that amount to above three square miles.2 Though many rulers have passed the city since that time, the statute of the palace still commands its presence—an apt location for Belgian contemporary artist Luc Tuymans’ La Pelle, a large-scale survey exhibition of his work presented at Palazzo Grassi running nearly a year.

Upon entering the space, the visitor first encounters a large-scale marble mosaic; marine-green on warm white, the floor-based work is titled Schwarzheide (2019), based on a 1986 painting by the artist carrying the same name. Schwarzheide, from German, translates to “Black Pagan,” and is the name of a World War II Nazi concentration camp located just north of Dresden. The image, an elementary gestural outline of a forest, placed on top nine even vertical stripes, evokes the conflicted streams within the modernist tradition—one can imagine an abstracted landscape painted over Agnes Martin. The composition derives from a secondary source: Tuymans took the image from a book of drawings by Alfred Kantor,3 a Holocaust survivor who, after the war, drew his experiences from memory.4 Though the viewer encounters the mosaic upon arrival, they cannot really see it, not fully. They are too close already.

At the top of the first sweep of the grand staircase leading to the next two floors is a small painting, Secrets (1990). It is a close-up portrait of suited man, in dark muddy tones, that appears to be aging. The work is a portrait of Albert Speer, the chief architect of the Nazi party and the Third Reich’s Minister of Armaments and War Production. With eyes shut, Speer evades the viewer’s gaze, persistent in the concealment of horrific secrets.5

From the onset, the space confronts the viewer with that which still remains untold, and that which cannot be comprehended.

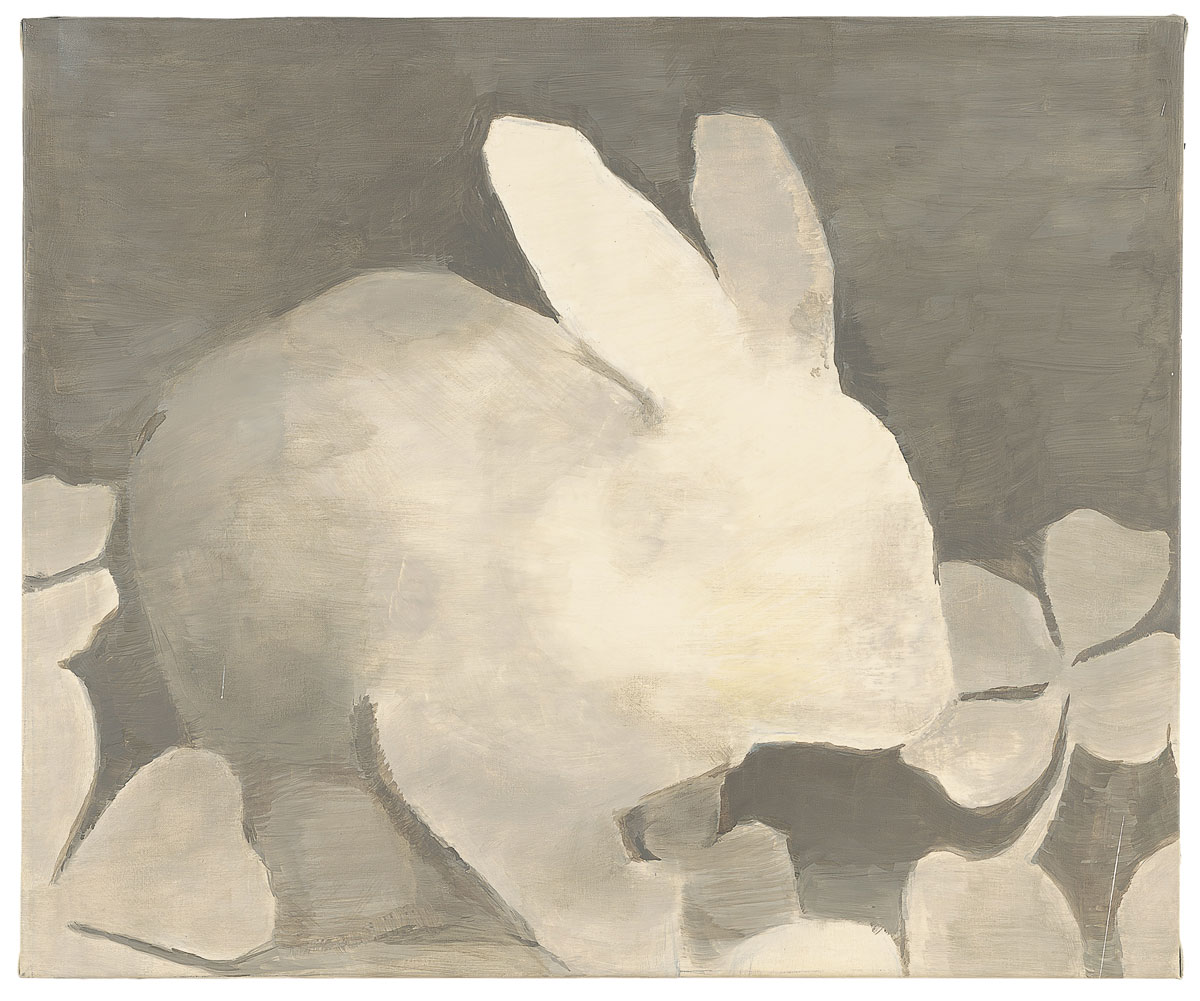

La Pelle is organized not through a chronological procession, but as a series of visual arguments. In the first room, a large-scale painting of what seems to be a landscape is juxtaposed with a small still life. Loosely painted, Mountains (2016) presents a rudimentary composition of arid hills and a stream of water. With no horizon, no sublime, the painting turns its back to the 19th century German Romantic tradition led by Casper David Freidrich. Instead, its hues bring to mind an overexposed photograph, disintegrating into murky white and dry copper tones. But this will be a misreading of the work. The landscape here is not depicted, it is composed. Tuymans constructed it out of aluminum foil and soil.6 Body (1990), an early work of Tuymans, depicts a frontal torso of a child with their head cropped out. The viewer is faced with an immobile corpse, which evokes a deep psychological disturbance. Though the viewer is informed by the exhibition’s printed guide that the painting is based on a stripped-naked cloth doll, the information does not allay the malaise that the painting is imbued with. The painting appears as old, as rediscovered, as a latent imprint of an early trauma that one successfully repressed up to this point. This effect is not coincidental. Painted with a few brown brushstrokes on top of a light creamy background, Tuymans applied the paint while intending it to crack, as if to signify false aging.

The second room presents a triptych of large-scale animalistic eyes. Pigeons (2018), a series of monstrous blow-ups of zoomed-in pigeons’ eyes, is painted with muted yellowed-pinks and dark purples. In each eye, a glare that seems to be not in the painting, but added onto it, acts as an additional distortion to the already threatening presence that the paintings possess. As if from the flash of a camera, this glare evokes an eerie effect of being watched, which is amplified through the paintings’ placement. The triptych is hung in a room with three arches that open into the inner courtyard of Palazzo Grassi’s architecture, and therefore can be seen from the different floors.

While walking between the galleries, a strange sensation emerges. On the one hand, the viewer is cast within the shadow of surveillance, of being watched; on the other, they cannot fully comprehend the paintings that seem as if they are being erased in front of their own eyes. Presented in “a state of undecidability,” as Ralf Rugoff stated of Tuymans’ works, they “make it difficult to feel that we have ever finished with our scrutiny of them.”7 Painted wet on wet, with thin layers—some reflect the light while others absorb it—the paintings feel like they are going out of focus. Contours are not drawn, they occur. Jarrett Earnest defined this effect as “visual static,” that pushes the image to the “brink of intelligibility.”8

This tempo is not unfamiliar to Tuymans. In fact, one can ironically define it as his benchmark or style.9 Known for his spectral, muted palate, Tuymans’ paintings, which are most often based on secondary photographic representations of found images, tackle a wide range of political and historical subjects, including the Holocaust, Belgian colonialism, Conservatism in the United States, child sexual abuse, and the Church. The grand subject matters are appended with paintings of reality TV shows, Netflix series, viral YouTube videos, Disney, and more. It has been said that Tuymans has painted everything, but this statement would be wrong.10

“I am in the profession of silent things.”—Poussin11

With the wide circulation of Tuymans’ reproductions, it may seem as if many know his work—yet what many have actually encountered are only images, not his paintings. In the age of Instagram and the dissemination of the Internet, people too often forget that paintings exceed their visual information. The effects of their surfaces, the syntax of their gestures, the complexities of their tones, are all omitted in a photograph, because painting is completely physical. Painting is present in relation to the viewer’s eyes and body—it changes with the different architectures it inhabits, and the light that is cast upon its surface. Looking through Tuymans’ reproductions, one can misidentify a style, while in fact his work is produced in an antisystem. In front of the works in situ, one does not encounter stylistic tropes, but rather material constraints and singular attentions.

Images carry discursive content, a fact that Tuymans eagerly employs with endless interviews, books, symposia, and so on. Paintings, on the other hand, are mute. Tuymans’ paintings evoke a particular kind of silence, one that can be analogized with the static sound generated by a TV device on mute. A silence of floating images. The paintings are neither doors nor windows to enter or peer through. Presenting “a different form of frontality,” as Bill Horrigan noted,12 they are screens to be confronted with. And yet, with encounter, the silence persists, and amplifies the paintings’ “lack of legibility,” as Helen Molesworth identified.13 Surpassing comprehension, the paintings are submerged in silence. Their silence marks a gap between the works themselves and an assumed meaning. It is a violent process of self-erasure, which pushes and resists the trace. This gap of comprehension shakes loose an undetermined emotional tenor within the viewer—it magnetizes them to come closer, to step away, to listen, and to look, as if secrets are about to be revealed. This is the feeling that remains and grows after the departure from this survey.

Tuymans often speaks of violence as an underlying structure of his work.14 One may observe that violence defines the artist more broadly. Born in 1958 near Antwerp, where he still lives and works, Tuymans belongs to the postwar generation that was born shell-shocked. Though the bombs fell years ago and the streets are clean again, he is a part of a generation that was confronted with “experience” as an imminent traumatic break. Tuymans’ is the son of a Dutch mother and a Flemish father. While the Dutch side of his family was in the resistance, the Flemish side collaborated with the Nazis. His father’s brother, whom he was named after, was in the Hitler Youth; a fact that Tuymans learned from leafing through a family album.15 ”It was a very unhappy marriage, so whenever we sat down to eat, this whole bullshit came up again,” he recounts, “it became a phobia for me.”16 Tuymans’ preoccupation with history and its effects on the present are tied into his own biography and with his own early experience. Thus, his ongoing focus on humanity’s capacity to annihilate itself is not just an intellectual pursuit that he amuses himself with. Rather, it is the horizon that his parents were once faced with. This history, which brought with it the potentiality of the end of history, was handed down to Tuymans and his generation not as “experience,” but as images and their absence. A process that produced an ambiguous state of mind that equated, and eclipsed images with experience. In Tuymans’ words: “I grew up with television. I mean that I grew up much more with images than with experience.”17

With the twenty-first century spread of screens—from television to computers, iPhones, tablets and so on—the entanglement between experience and images became far more pervasive (bring back to mind Instagram vs painting). While in the past the image served as a trustworthy agent in the chain of signifiers, currently, the only way to consider images is as free radicals, signifying multiplicities, and nullifying signification in a whim. Tuymans identifies this situation: “nowadays, the image has arrived at an end-point in terms of what is real within the context of the imagery…The present condition—the ambiguous state of mind and a visual ambiguity—is now here to delve into. It is a difficult kind of research, because all references are intertwined with the imagery. Nevertheless, it is also a completely blank slate, which is an interesting challenge.”18

This “ambiguous state of mind” and “visual ambiguity” can be exemplified by tracing a map of images, even if only mental images, which the Palazzo Grassi’s exhibition title evokes. La Pelle, from Italian, “The Skin,” takes its title from a novel by Curzio Malaparte (1898–1957). Set at the end of World War II, the novel depicts the immeasurable suffering of the residents of Naples, whose state, with the Americans’ landing, seemed to grow only worse. Arriving as liberators that “help” the locals—who in return “should be so lucky”— the Americans perceive themselves with high morals. This they do while fetishizing the residents to their basic cores, reducing them to objects of commodity.19 Published in 1949, La Pelle was met with complete outrage and banned both by the Vatican and the city of Naples.20 Its author, Malaparte, had a taste for scandals. An avid Fascist, he marched with Mussolini on Rome in 1922 and was a member of the Fascist Party until falling out of Mussolini’s favor, which led to his repeated arrests in the late 1930s and early ‘40s. Malaparte was born as Kurt Erich Suckert, to a German father and Italian aristocratic mother. He changed his name to Mapalarte, as a punning inversion of Napoleon’s surname, Bonaparte.21 Unlike Napoleon, he decided that he was destined to be on the bad side. In 1938, Mapalarte built, together with the Modernist architect Adalberto Libera—who was also affiliated with the Fascist Party—the Villa Malaparte, a spectacular building on the verge of a stiff cliff in Punta Massullo, Capri. The Villa appears in a painting by Tuymans’ entitled Le Mépris (2015). But unlike the villa, with its spacious architecture—its interior is open to the Mediterranean ocean in an almost 360-degree angle—Tuymans’ work is of a blocked view. It depicts an interior wall with a small window, its view to nowhere, placed atop of a massive fireplace, with no fire.22 The painting’s title refers to Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film, starring Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli,23 in which the villa’s architecture plays a central structural role. Being one of the most critically acclaimed films by Godard, it is highly structural, presenting a synecdoche of a sort, in what seems to be an endless net of self-references. To close a full circle, Godard’s Le Mépris is based on Alberto Moravia’s 1954 novel Il Disprezzo(from Italian: A Ghost At Noon), which focuses on the fetishization and disintegration of human relationships; that the novel reverberates the themes presented in the book La Pelle is no coincidence. The authors knew each other—in fact, Moravia and Malaparte were friends.24 This map, that traces historical, cultural and fictional references, intertwined to a point of oversaturation, exemplifies Tuymans’ endeavor. He is a man who is obsessed with images to a point of exhaustion. Following Hannah Arendt’s analysis of evil as “terrifyingly normal,”25 the artist continuously avoids using images of horrific historical events. Instead, he collects the “normal” moments before or after.

In 2002, upon accepting an invitation to participate in Documenta 11, and in response to 9/11, Tuymans painted Still Life (2002), a composition of fruits and a jug of water on an immense scale (nearly 11.5 by 16.5 feet in size). Reversing between the intimate and low-ranked genre of still life painting and the genre of history painting, which traditionally occupies a monumental scale, the painting becomes a carved gap that obliterates the possibility of representation of horrors of historical events.26 Instead, the painting presents air, nothingness; its immense faded fruits seem to float in a non-space, in an outrageously pleasing manner, and though the painting turns to the history of painting—formally conversing with Cézanne’s unfinished watercolors, which Tuymans encountered in Reinhart collection in Winterthur—Still Life is stupefying and painfully banal.27

Banal images: they are lodged onto Tuymans’ vision. It can take months, and even years, for the images to be released onto the canvas. In this incubation state, the images morph. They are drawn, painted with watercolors, manipulated in Photoshop, reproduced as tiny maquettes28 and then shot as Polaroids or as printouts from an iPhone.29 When the image is exhausted, Tuymans paints it in one day.30 He describes this process as a shift in intelligence from his mind to his hand.31 Working on canvas stretched directly to the wall,32 the reference image is never projected.33 Instead, via the aid of a polaroid or a print, the image is drawn with a pencil on top of a layer of luminous white, which allows the painting’s boundaries to be defined from within.34 This self-imposed time limitation forces the painter to work wet on wet, with heavily diluted layers that are often being misrecognized as greys, or “noncolor” tones,35 but actually contain a range of colors. Black is never used due to its flattening effect. Dark tones are applied selectively over the light ones, towards a slow contrast. To use the language of photography, the paintings are “developed” in front of the artist’s own eyes, not unlike the Polaroid.36

This uniquely intense practice, which is framed by time—one day—underlines the artist’s conceptual frame. The process is divided always into two stages, the first is of the image’s conception, during which the image is studied through manipulation to complete exhaustion leading to the second stage. The artist’s knowledge is redirected to his hand and the painting is produced, again, in one day. The outcome is a work that begs the question regarding the limits of the seen, the remembered, the forgotten and the erased.

“When I am looking at Tuymans’ work,” wrote the art critic Peter Schjeldahl, in 1996, “it seems to me absurd that our culture does not embrace painting normally and avidly as an enthusiastic matter of course.”37 This curious sentiment—of painting being abnormal, and our culture’s inability to embrace it, also reverberates in Molesworth’s 2009 essay, where she discussed Tuymans’ practice: “once this project might have been warranted calling him a history painter, but the battered nature of painting is such that the designation feels too antiquated to be useful.”38 Molesworth goes further and attempts to save the artist from the “battered nature” of his medium by replacing the category of “Painting” with “Art.” While her post-medium-based discussion leads to potentially interesting theoretical investigations, it misrecognizes, and therefore misreads, Tuymans’ corpus, which lays within the painterly realm. And yet, both texts, that of Schjeldahl and of Molesworth, present a symptomatic misrecognition of painting as obsolete. One may lean closer and hear a whisper: “the death of painting.”

Painting is still too often considered to be traditional, capitalist, bourgeois, and everything that a left-oriented scholar would like to avoid touching. Robert Storr described this attitude in 2003, during an Artforum International panel, stating that “many scholars and curators are disinclined to talk about current painting even though they are drawn to it, because painting as a subject has been disallowed by those who preside over their training and have a hold on their futures.”39 What Storr describes here is a historical discourse that nowadays imprints itself latently, as a repressive force; a postmodernist assertion that keeps proclaiming painting to be reactionary, enslaved to the culture industry, reactionary, romantic, decorative, and so on. Where do these tenets come from?

In the winter of 1980, Douglas Crimp publishes an article titled “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism,” which is swiftly succeeded by a following text, adorning the subtle title, “The End of Painting.” Both appeared in October Magazine—the pieces constructing an ideological argument, not surprisingly, against painting. Basing his theoretical constructions on a limited reading of Walter Benjamin’s texts, Crimp first situates painting against photography, emphasizing on photography’s radical quality as an unoriginal copy.40 Then, after accusing painting of being complacent to the bourgeois culture and ideology, Crimp aptly announces it as dead. Lastly, deterring any attempts of its resurrection, Crimp declares that “[t]he rhetoric which accompanies this resurrection of painting is almost exclusively reactionary.”41 The same issue of October also published an article by Benjamin H. d. Buchloh, titled “Figures of Authority: Ciphers of Regression.” A text that resonates with similar murderous intentions. Buchloh, who was not wholly against painting—being Gerhard Richter’s friend and a devout supporter—writes only against only the “representational,” “expressive” and “sensuous” values in painting, which he condemned as reactionary, conservative, and authoritarian.42 Soon after the issue’s publication, Craig Owens, Hal Foster, and Rosalind Krauss also joined the fight.43 Throughout the many arguments presented by the group in the subsequent years, painting was repeatedly accused of embodying pleasure and sensuality, qualities that defined it as a desirable object of commodity, and therefore, inherently corrupt.

These arguments, despite the theoreticians’ best intentions, exude a Greenbergian ideology.44 The distinction between the avant-garde and kitsch was kept intact. “Good” art, meaning the avant-garde, was identified via its purifying qualities. It was challenging, unfamiliar, and progressing towards a better good.45 Meaning, the October Magazine critics kept propagating the modernist ideas that it was supposedly opposed to. While one can read these arguments as serious attempts to resist the culture industry, despite their polemic nature, one cannot ignore the fact that they have failed. Photography, as well as new-media genres that followed it, are equally, if not more aptly, folded nowadays into the cultural marketplace.46

This discourse, once spurred by the art world rebels, now is institutionalized, despite its failure, and regurgitated by those who became the cultural elite. While many of the discourse’s arguments can be read today as iconoclastic, dogmatic, and even tyrannical, their impacts still persist. This is the state which is outlined in Robert Storr’s assessment, that “many scholars and curators are disinclined to talk about current painting… because painting as a subject has been disallowed by those who preside over their training and have a hold on their futures.”47

With this in mind, we may consider that in a strange reversal in relation to Tuymans’ work, painting, which confronts these theories, produces nowadays an institutional critique. Precisely because it is no longer in the center, painting becomes more vital. Or, as Tuymans’ says, since “thought is most interesting at the edge.”48 Devoid of false modernist intentions, painting does not attempt to predict an end to history. Painting, and one can claim that the artwork at large, enacts a plural relation to time. While being produced in present, it is also always tied to other times, and to that which is outside of it. It has “the power to compel but not to explain a folding of time over onto itself,” as Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood outlined.49 Tuymans defined it to be of “anachronism,” which is not equal to “anachronistic,” a term that carries a tone of judgment, insinuating of a work’s failure to fall in line and be in its “proper” linear time.50 To discuss art as an anachronism is to depart the current historicist “forensic reconstruction of the past,”51 and to produce a meaningful conversation across time. One can bring to mind the net of images that was traced with title La Pelle; a net that keeps spreading to different times, outside of the time of this text.

And yet, an artwork is also always a symptom of its time. Tuymans’ work presents the latent symptoms of our cultural disease. Failing to stabilize it, to imprint it in our memory, the paintings’ specters linger. We are doomed to fail, we will not remember, but we may remember this time our desire to forget.

Luc Tuymans: La Pelle at Palazzo Grassi ran from March 24, 2019–January 6, 2020.

- Valentino Volta, “Massari, Giorgio,” Grove Art Online, 2003.

- Martin Bénédicte,Pinault, François,” Grove Art Online, March 2018.

- Alison Gass in Luc Tuymans, ed. Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009) p. 75

- Tuymans returned and worked with the book for more than once. Our New Quarters (1986), also on view at Palazzo Grassi, is another painting that uses the book of Alfred Kantor as its source of imagery. (Jason Farago, “An Interview with Luc Tuymans,” Even Magazine, December 31, 2017.)

- Albert Speer, despite being one of Hitler’s closest aides, insisted to his death that he was not aware of the “final solution.” (Michael Z. Wise, “Book Review: Hitler’s Words into Stone”, Wall Street Journal, Apr 13, 2013, Eastern edition.

- Palazzo Grassi, “Mountains, 2016,” exhibition text, 2019.

- Ralph Rugoff, “Luc Tuymans: Inside the Box” in Luc Tuymans (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), p. 53

- Jarrett Earnest, “Crimes of Dispassion: Materiality and Reality of Images,” in La Pelle – Luc Tuymans, Patricia Falguières, et al., (Venezia: Marsilio, 2019), p. 36

- And one did; Jordan Kantor coined the term “the Tuymans effect,” in a widely quoted article from 2004, carrying the same title. In it he discussed the pervasive influence of Tuymans’ style on a younger generation of artists. (Jordan Kantor, “The Tuymans Effect,” Artforum International 43, no. 3 (November 2004): pp. 164-171). Tuymans, while discussing “style,” regards style to be“the death of everything.” Instead, he analogizes his mark-making to “handwriting,” or “riding a bicycle,” which one may understand as a process of making that does not necessitate a continuous doubt. (James Farago, Even Magazine).

- Gerrit Vermeiren, “Noise”, in Gerrit Vermeiren, Dieter Roelstraete, and Montserrat Albores. Gleason, Luc Tuymans: I Don’t Get It (Gent: Ludion, 2008), p. 21

- Pierre Rosenberg and Keith Christiansen, Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 286

- Bill Horrigan, “Tuymans, Cinema, Belgium, Tuymans: A Note” in Luc Tuymans (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), p. 60

- Helen Molesworth, “Luc Tuymans: Painting the Banality of Evil” in Luc Tuymans (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), p. 17

- Joseph Leo Koerner, “Monsters”, in Luc Tuymans (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), p. 39

- Kelly Klaasmeyer, “Luc Tuymans: ‘Nice’ Is Just That and Nothing More,” Houston Press, April 2, 2016.

- Cristina Ruiz, “Luc Tuymans: ‘People Are Becoming More and More Stupid, Insanely Stupid’,” The Art Newspaper, (March 29, 2019).

- Eric Suchere, “Luc Tuymans: More than a Medium,” Art Press, (July 2002), p. 28

- Luc Tuymans et al., The Image Revisited: Luc Tuymans in Conversation with Hans De Wolf, T.J. Clark & Gottfried Böhm. Antwerp: Ludion, 2018. p.181

- Rachel Kushner, “Introduction,” Curzio Malaparte, The Skin, (New York, NY: New York Review Books Classics: revised ed. edition, 2013), p. vii

- Rachel Kushner, “Introduction”, Curzio Malaparte, The Skin, p. xiv

- In Italian, ‘Bonaparte’ means ‘good side.’

- Le Mépris was also the title of a 2016 show by Tuymans, in David Zwirner, New York.

- Caroline Bourgeois, La Pelle – Luc Tuymans, p. 15

- Rachel Kushner, “Introduction”, Curzio Malaparte, The Skin, p. vii

- Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (London: Penguin Books, 2006), p.126

- Tuymans was in New York at the time of the attack, which he witnessed from his hotel window (Cristina Ruiz, The Art Newspaper).

- Luc Tuymans and Peter Ruyffelaere, On & By: Luc Tuymans (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 2013), p. 77

- As is the case with Mountain, which was mentionedearlier.

- Amy Bernstein, “Luc Tuymans: Interview,” Painters’ Table, (June 2014)

- Farago, Even Magazine.

- Ben Eastham, “A Necessary Realism: Interview with Luc Tuymans,” Apollo Magazine, (December 11, 2018).

- Kate McCrickard, “The Distant North of Luc Tuymans, Exhibition Review: Suspended – L’Oeuvre Imprimé (1989–2014), La Louvière,” Art in Print (July 2015), p.21

- Bourgeois, La Pelle – Luc Tuymans, p. 15

- Patricia Falguières, “Before the Image,” in La Pelle – Luc Tuymans p. 192

- Ibid. p. 191

- Ibid. p. 37

- Peter Schjeldahl, “Bad Thoughts,” The Village Voice (October 8, 1996), p. 86

- Molesworth, Luc Tuymans, p.17

- Storr, Robert, Carroll Dunham, Helmut Federle, Tim Griffin, and et al, “Thick and Thin,” Artforum International, Vol. 04, 2003, pp. 174-179, 238, 240-241, 244.

- Douglas Crimp, “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism Author”, October, Vol. 15 (Winter, 1980), pp. 91-101 and Douglas Crimp, “The End of Painting”, October, Vol. 16, Art World Follies (Spring, 1981), pp. 69-86

- Crimp, “The End of Painting,” p. 78

- Benjamin H. d. Buchloh, “Figures of Authority: Ciphers of Regression.” October, Vol. 16, Art World Follies (Spring, 1981), pp. 39-68

- Alison Pearlman, Unpackaging art of the 1980s, (University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 148

- Ibid. p. 11

- Leonard Diepeveen and Timothy Van Laar, Artworld Prestige: Arguing Cultural Value, (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. 2013), p .191

- Pearlman, Unpackaging art of the 1980s, p. 307-308

- Storr, “Thick and Thin,” Artforum International.

- Suchere, “Luc Tuymans: More than a Medium,” p.28

- Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, (Zone Books, 2010), p. 10

- Eastham, “A Necessary Realism: Interview with Luc Tuymans,” Apollo Magazine, (December 11, 2018).

- Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, p. 18