Tobias Zielony: Berlinische Galerie

by Tara Plath

The Tobias Zielony exhibition, just recently closed at Berlinische Galerie, was comprised of two projects: Trona, 2007 and Jenny Jenny, 2013. Built upon documentary-style photography, both projects present devastated narratives with recurring characters and foreboding sets. Zielony’s career has been defined by a history of photographing the youth from decaying communities. His subjects are both fully self-aware of, and completely embedded within the stage that Zielony’s camera depicts.

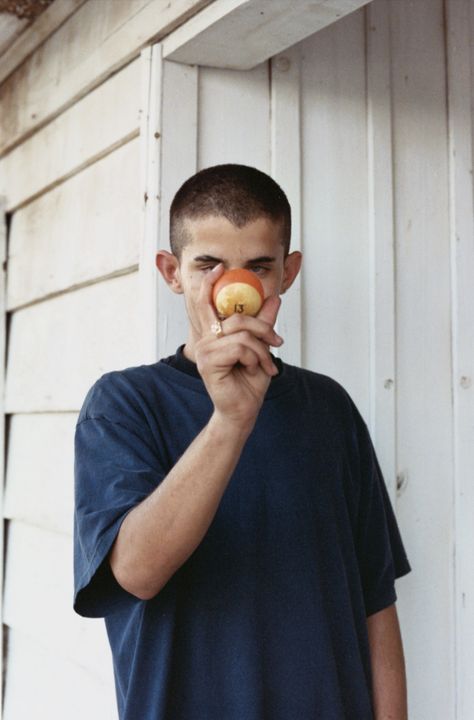

Trona is a collection of documentation from a small California desert town of the same name. It includes a series of color photographs, 80 slides of unattributed quotations, and two pages of text mounted to the wall at the far end of the space. In the photographs, some of the subjects are named while others remain anonymous, enforcing the series to function cinematically, like a silent film of pure idleness. Bleak and washed-out landscapes are contrasted with darkly clothed unkempt youth.

The slides of text construct a clear picture, saturated by American tropes, of a town in economic and cultural crisis. “Trash begets trash,” one slide concludes, condemning Trona as a quarantined cesspool of this generation’s American nightmare. The “kids” are meth heads, and most of the adults work at the same chemical factory that looms just behind homes in the adjacent photograph, Factory. There is a palpable distrust of the corporation—the one thing that sustains the town, but refuses to invest in it – all while producing chemicals that have poisoned the ground. Trona is a destination only for runaways and criminals. The homes are cheap and cheaply made, and often set ablaze by vandals.

I found myself trying to credit each quote: some are clearly from youth living within the town, others from people familiar, but outside of it – and some still have a sensation of being the artist’s own words: judgements aimed pointedly at these people “too stupid” to leave. This, of course, is most likely in part due to the paranoia of being the sole American viewer, surrounded by a local Berlin high-school class, who whispered and giggled as the slides passed by with references to “tweekers” and “teeny-boppers.” As an American, the story presented by Zielony produced both feelings of embarrassment and a callow sense of empathy. As such, Trona is impersonal, distinctly marked by exteriority: both that of the photographer as outsider, and the outdoor setting of each photograph. Zielony does not take his photographs inside the home, he takes them of a family forcibly posed in front of their house, from the street. Through the linear viewing of the display, one moves past the work as though it were a panoramic view of a small decaying town isolated by dry and stunted mountains. It reads like a study of detached observations: a petri dish that holds the by-products of all-too-American corporate interests.

The reduction of a country to a white-trash stereotype is turned around and made self-aware by the inclusion of a found document in Textafeln, describing the “REAL Nazi way to make methamphetamine.” The instructions, most likely found online but assumed to circulate within Trona, are written by “Speed Demon,” who boasts of providing you with the key to producing “high quality shit.” One is then faced with the glaring reality of the drug itself, in the list of ingredients that include lithium batteries, starter fluid, and aluminum foil. Zielony smartly brings the work home, both through a means of distribution of information within the Berlin gallery, and by the self-reflective evidence of an American’s view of no Germany without Hitler and his “amazingly BAD IDEAS.” One might pause to dwell on the tragic irony of Speed Demon attributing the crimes of Hitler to the drug, while promoting his own craft of producing it.

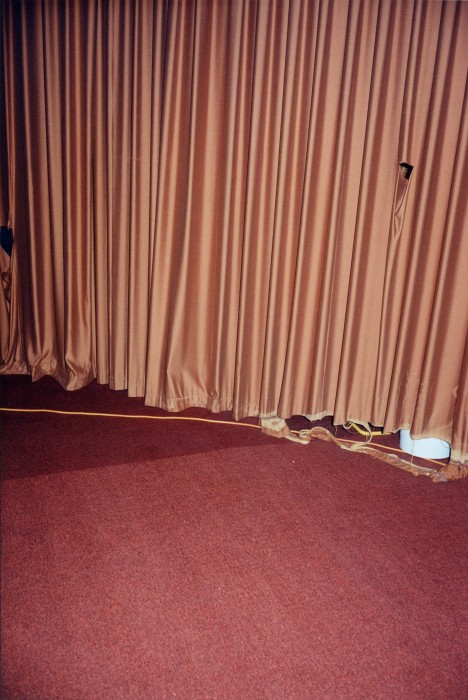

Jenny Jenny is composed of a nearly overwhelming collection of photographs, in addition to a single photo-animation entitled Danny. While the photographs present themselves in a documentary fashion, Danny is carefully edited and dream-like. It is a faint memory suddenly called to mind for its strobe-light quality of pulsing images. A woman stands in the dark on the side of the road, behind a string of red lights and waving glow sticks in each hand. She smiles playfully, posing in a too-tight, low tank top and heels. At times, we see only the glow sticks – dangling on a branch in the dark of the forest, the woman nowhere to be seen. The performative qualities and manipulation of the film made so apparent in Danny casts its fiction over the entire collection of photographs, which may now even be questioned in terms of a hedonistic narrative. Standing in the middle of the exhibition, surrounded by images of sexualized women and girls, the visible grain of the digital images produces a filter of home-made videos; at once seedy and disturbing. The viewer is repeatedly confronted with evidence of damage and marks of time in the forms of scars, burns, and decay.

The photographs weave between sultry and squalid. Jenny Jenny is defined by the surface: painted nails, grafitti, glassy eyes and a hand pressed against a mirror. In one photograph, a woman lies upon a bed, her face heavily laden with make-up; it seems almost as if a beauty mark has fallen off her face and manifested itself in the cigarette burn on the bed sheet. She is one of several woman who engage directly with the camera – the man holding the camera, the viewer, and the client. Perhaps most disturbing are the recurring images of Steffi – we are indicted for our repeated and lingering gaze of her exposed body, which cannot belong to a girl older than sixteen, though her pierced nipple suggests otherwise. Zielony has come to know these women after photographing them for two years, though this is not always evident since their poses never feel more familiar than their occupation might require. An exception is made perhaps in Muster, where a young woman stands awkwardly half-dressed and modestly posed, standing straight against a wall with her hands behind her back. However, even this vulnerable moment refuses the viewer – heightened by Zielony’s decision to crop her face out of the photograph, forcing the viewer’s focus instead onto her body, and the bed beside her.