Walid Raad: MoMA

by Tara Plath

This text is (here and there) a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

This small print follows the text of Lebanese artist Walid Raad’s walkthrough/presentation of Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, first presented at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel and now included in Raad’s first American survey currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art. Raad’s performance-lecture runs every few days throughout the exhibition, activating the densely packed layers of information and oblique formal compositions presented in the second floor atrium.

It is a useful piece of information, as small print often is, when regarding Raad’s practice. One can be sure, coincidence has very little to do with this enigmatic artist’s work. Thoughtful and airtight, the moving pieces of Scratching on things… revolve around narratives that waver between fiction and fact in a category unto themselves. Raad acknowledges this himself at the commencement of his presentation when he explains that what he is telling us are fact-facts, not fictional facts. True or not, it doesn’t matter—and I recommend you leave it there.

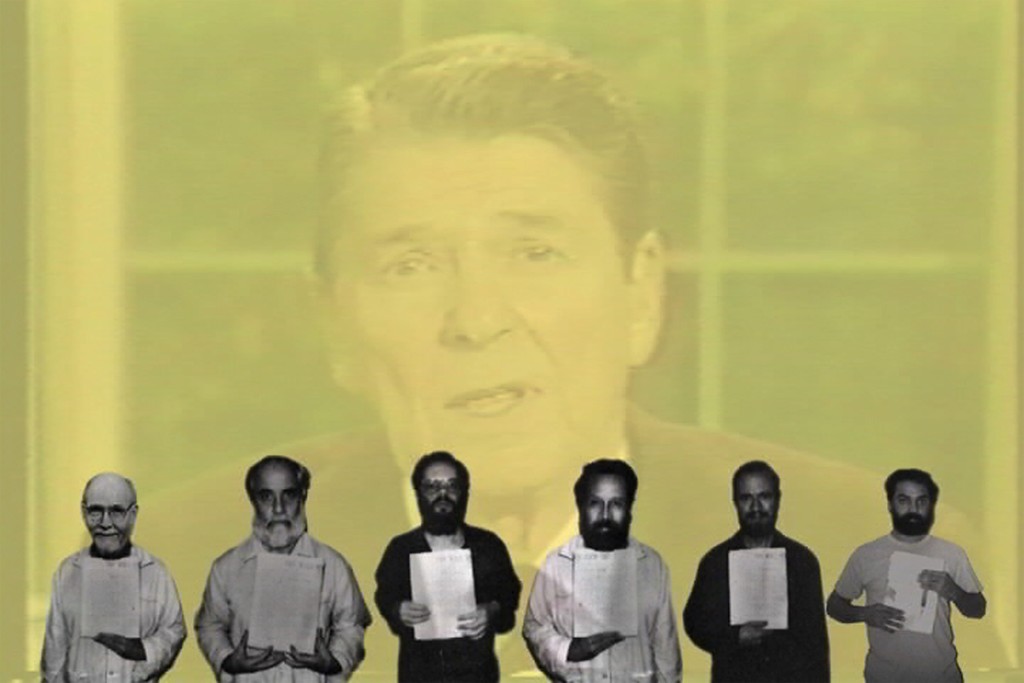

Over the course of thirty-five minutes, the charismatic artist paces around the gallery describing his findings over the past eight years, beginning with an investigation of the Artist Pension Trust, or APT. Raad first stands in front of a large wall covered in arching info-graphics, including lists of names, cut out faces and faces cut out, with a projector highlighting details and overlaying infomercial imagery. He describes in compelling fashion his invitation to join the APT, ensuing inquiry into its investors and participants, to eventually connect the dots between its founders, data-analyst aficionado Moti Shniberg and risk management expert Dan Galai, Israeli intelligence, and MutualArt. Upon an introduction to the man himself, and an attempt to uncover the connections, Shniberg tells Raad, “Please don’t tell me that you are one of those naive left-wing, head-in-the-sand pontificators who actually think that the cultural, technological, financial, and military sectors are not, and have not always been, intimately linked?” As the antagonist, the artist describes how the veil is lifted from over his own eyes and politely declines involvement in the APT, describing personal conflict as opposed to ethical high ground—Raad posits his apprehension in his position as a Lebanese artist, for whom any connection to Israel runs the risk of fatal damage to his career within his home country and beyond.

This is a delicate and generous move on Raad’s part, here and throughout his work. He does not shine high beams on his viewers’ ignorance, nor does he assume illiteracy in the subject matter. Rather than force a lackluster aesthetic object upon an uninformed viewer, Raad’s performance provides us with information, clearly and concisely, that illustrates the art market’s relationship to unsavory global forces. These connections are taken for granted by some and not ever considered by others, and Raad speaks to both groups.

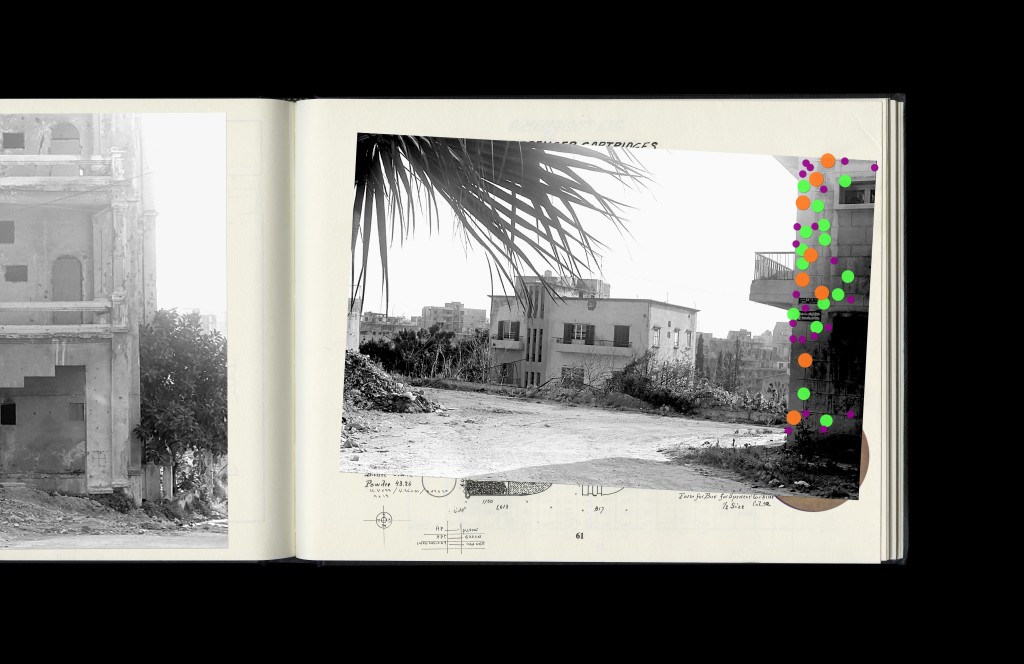

One floor above is the second part of the exhibition, encompassing the work of The Atlas Group. From 1989–2004, Raad worked under the auspices of a non-profit foundation dedicated to archiving documents related to contemporary Lebanese history. Abstract and amorphous, with changing dates of incorporation and Raad as the singular member, The Atlas Group served as a vehicle for Raad’s conceptual paradigm. Included in this part of the exhibition are several groups of photographs with accompanying text written in the style of an inventory, such as My neck is thinner than a hair—a collection of framed photographs documenting various engines, the only thing to remain intact following car bombs. Most wall labels include summaries describing the material according to the individual who donated it to The Atlas Group. It is all generated by Raad, not from imagination but from the artist’s own first-hand documentation throughout the Civil War.

Perhaps most exemplary of Raad’s practice are the works Appendix XVIII: Plates 22–257 and Les Louvres (Département des Arts de l’Islam), both of which involve mysterious transformations in material. In the case of Appendix XVIII, color, line, shape and form once perfectly apprehended suddenly becomes invisible following decades of war in Lebanon. According to Raad, these aesthetic qualities are “hide, take refuge, hibernate, camouflage, and/or dissimulate.” They embed themselves in various places, their favorite hiding place being academic dissertations about the region, written in English of course. Alternately, the series of objects included in Les Louvres, objects loaned to the Louvre Abu Dhabi underwent unexpected transformations while traveling in crates from Paris to Saadiyat Island. When unsealed at their destination, it was discovered that the objects had “traded skins,” resulting in ornamental surfaces incongruous with their extruded forms. The far-fetched and paradoxical nature of these works is disorienting, and demanding of the viewer.

In Les Louvres, Raad toys with the idea of the substance of an object being malleable depending on its environment. It is not an easy task to charge someone with accepting the potential for psychosocial states or national borders to affect physical objects. In the United States, we continue to stand on seemingly stable ground, prone to reactionary politics and knee-jerk responses to unfounded claims. Perspective is often seen as a concept better left alone, lest it get in the way of fact. Raad’s survey works against these things. It is slow and somewhat obscure. The exhibition requires two things: active participation—the conscious decision to engage with material that is deliberately unclear—and a suspension of belief, a challenge well worth anyone’s time.

The exhibition will travel to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston February 24–May 30, 2016, and to the Museo Jumex, Mexico City, October 13, 2016–January 14, 2017.