Wendy Red Star: The Maniacs

by Michelle Lanteri

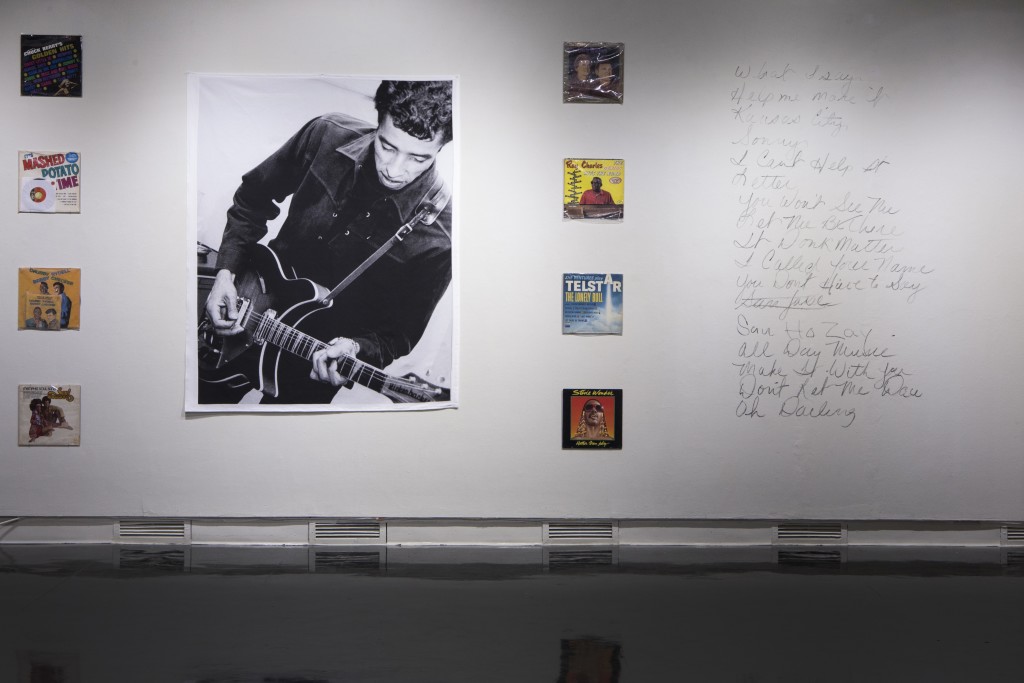

Portland, Oregon-based artist Wendy Red Star’s (Apsáalooke [Crow], b. 1981) touring exhibition, Wendy Red Star: The Maniacs (We’re Not The Best, But We’re Better Than The Rest), honors her father Wallace Red Star, Jr.’s musical career and service in the Marines, transforming the contemporary art cube into a hall of fame. Focusing on The Maniacs, her father’s 1960s-70s all-Crow rock ‘n’ roll and blues band, Red Star designed a multisensory installation to imbue the locally-renowned band with celebrity status and give form to the strong, positive impact they had on the Crow Indian community in Montana. A fan said to Wallace Red Star, Jr. years later, “The white kids had The Beatles, and we had The Maniacs.”

Michelle Lanteri: When did you start thinking about The Maniacs exhibition? Tell me about your initial take on the significance of this band and how you have learned more about them in your research.

Wendy Red Star: I started thinking about The Maniacs in 2015 and 2016, and I officially said to myself that I was going to do this exhibition then. But at thirteen or fourteen years old, when I first saw the promotion shots of my dad, Uncle Kevin, and Kenneth Toineeta in my Aunt Kaneeta’s photo album, those images really blew my mind. Back then, I saw my dad as a rancher, pilot, and horse-trainer kind of guy, but not this Jimi Hendrix-esque rock ‘n’ roller. I was so drawn to these photos; I ended up taking an image of my dad from my aunt’s album. My aunt died in 2015 and at Thanksgiving that year, she gave me all the photos of The Maniacs she had. This visit with my aunt was a big push for me to do a show on The Maniacs; I feel that she knew that I would be the right person to take care of those images. Also, my Aunt Redstar gave me a ziplock bag full of photos of my dad as a child and of The Maniacs, and my mom gave me slides that included some of my dad in Vietnam.

In 2016, after you asked me to do a show and I saw the real estate of the gallery, I thought—wow, this is perfect. I wanted to push this idea and give The Maniacs a lot of space for different aspects of the show. I did not know what it would look like until closer to the exhibition, but I had components I wanted to see.

The research involved a lot of phone conversations with my father. It bled into things like calling the local mortician to see if he had my Uncle Wendell’s obituary. I was also looking into guitars, Fender amps, different music genres, and vinyl records. In my practice, there is something really addictive about this process that has so many unknowns. I learn and educate myself, and then I put myself into situations or adventures, that I would not have thought of on my own.

ML: Why is this band so important to your family’s history?

WRS: The Maniacs did something very creative and took it to a new level because of their skill. It is important when people from a lower economic situation—like the band—pull themselves out of that situation and do something positive in the community. The Maniacs lifted themselves and their families up; people came from all over the reservation to hear them play. With so many things working against Native people in general, to see something so supportive is pretty amazing.

I also like that for my father, his first language is Crow. He did not speak English until he was eight. In my generation within my own family, only a few of us understand the language. I know words here and there; I would be seen as sort of bilingual. I grew up hearing Crow spoken at my grandmother’s house, so it is very familiar. Although, now there is so much shame around the language that has filtered to my generation. I think that trickles down from the boarding school era, even though currently there is a great movement to revitalize the Crow language.

With The Maniacs’ generation, they had that freedom of not feeling like they had to prove their Crow-ness or authenticity—a pressure that now exists. When the band performed, they did not put on any pageantry. They were comfortably who they were, and they were playing music.

ML: How did your exhibition ideas for The Maniacs change as you created site-specific concepts for the University Art Gallery at New Mexico State University?

WRS: That is the cool thing about showing work in a specific space. Even though I had components of what I wanted to be in the show, it was really the space that helped formalize and mold the feeling of the exhibition. Having the maquette of the gallery helped me curate my ideas and create the flow of the space—the hardest parts of the process. As the final component in finishing the work, the space sets the tone and experience for the audience, which is not something I have figured out when my ideas are formulating.

The long wall as the timeline made a lot of sense and really helps guide the viewer. The merchandise shop is a solidified, dedicated space at the very end. And as the show travels, the components will change for each venue. The exhibition will not look the same, and that will be an interesting challenge. New concepts may be added, while other elements may be edited out.

For me, it is like baking a cake. I have all the ingredients, but when I get to the space, I have to take a leap of faith and be open to changing things around. That can be hard when you are working with institutions who want a set idea. But when it is a brand-new body of work and the first exhibition space is the testing ground, I really appreciate it when the institutions and curators allow me to have flexibility. It tends to all work out somehow.

ML: The entire exhibition honors your family and provides entry points to audiences about their experiences with family members serving in the military. Can you speak to the juxtaposition and embodiment of these themes in your artworks?

WRS: Initially, I think I always work from the pure excitement and passion I have for an idea. With The Maniacs, it is very universal, as there is just something amazing about when you go to a concert. You are listening to music—you just feel moved. With this show, I wanted to tap into this kind of experience. The Maniacs is the most deeply personal, hardest body of work I have ever produced, but it is also the most rewarding, sophisticated work I have made to date. It is a big breakthrough for me. It took a lot to confront dynamics in my family that I did and did not know about.

I find all these different connection points in the research. Like the type of guitar my dad played when he was little is the same that Kurt Cobain played for a song. It starts out with that familiar point—I can broaden it from there. And, Las Cruces was amazing, because there is a connection between the city’s military background and environment, and the fact that I come from a military family. My mom served in the Army; my dad served in the Marines. At the opening, there was a Marine who had been at Camp Pendleton a couple years after my dad. Looking at the show images with him, he said that my dad was an expert sharpshooter. A week later, another Marine visited the gallery. He went to boot camp with my father—he had images with my father in them.

This exhibition let me honor aspects of my dad’s life—things that were not necessarily significant to him, like these snapshots, some of which are quite blurry. You never know how important images will be to the next generation, like they are to me. And, when the show travels, maybe the military experience will not be as pronounced; maybe another aspect will pop out.

ML: Let’s talk about The Maniacs merch store. How does this interactive space reiterate the exhibition’s notions of rock ‘n’ roll celebrity and music hall of fame?

WRS: I was thinking about myself as an extension of The Maniacs, like being their band manager, even though there is no longer a band. But I was thinking about things that they need to continue to go on tour. This is solidified through having merchandise. It is like when you go to a concert, and you have this full and amazing experience: there is a merch stand and you have to get a t-shirt. I wanted the viewer to walk away with something from the exhibition. Then they can share their own stories about The Maniacs and carry the oral history of the band forward.

The merch shop is a way for me to make objects, where the rest of the show is about using found images to tell a story. The merch shop lets me get creative and think about how to package The Maniacs for my leg of their tour. So, carrying this dream forward for the band, I envisioned that they wanted to tour all over and be these giant rock stars. And there is something about having them on a t-shirt that makes them more legitimate, more bona fide. Interestingly, the company I used to get the mugs, socks, t-shirts, and other merch flagged my hooded sweatshirt order—they thought this was bootleg merch. At that point, I knew I was on the right track.

ML: As a main visual element of the show, your timeline charting your father Wallace’s musical career includes reproductions of photo prints and slides and your handwritten annotations. Can you talk about the importance of this installation?

WRS: The original images are so precious to me; moving forward, I might have a display of them, even though they are quite tiny. There is something really great about enlarging each image. What I wanted to do with the photos—these intimate things—is make them into objects.

The purpose of me writing facts about my father, the time period, or the instruments on the wall is to ground the photos in the space. While writing, a lot of times I called my dad with questions, which speaks to how this work has allowed me to connect with my dad on a different level.

The writing is an opportunity to have people get closer to the photos. When I am looking at the images, I am looking at accessories that the people are wearing or what they are holding in their hands. If audiences engage with the images the same way I am, they get a better perspective. There is something very personal about it, like when you are reading notes on a bathroom stall. In the timeline, I can interpret that in my own way and give viewers that sense of experience.

ML: Green and orange are the accent colors of the exhibition, seen in both the merch store and stage installation. There’s also the huge wall with The Maniacs’ slogan, “We’re Not The Best, But We’re Better Than The Rest” in orange vinyl. Can you describe the retro design of these elements in relation to The Maniacs show poster you have?

WRS: This body of work has been incredible, in that it has placed me in a position where my family is willing to give me these invaluable things to let me be the custodian of them. My aunt gave me a set list. Then, my Uncle Aaron, who played the drums and did a lot of the band’s promotion including the band’s drum kit design, gave me a band poster that he made. It had the weirdest color combination, with a deep plum purple and a very specific orange and a green I had never seen before. The poster font is also a particular font that they used; it encapsulates the tone and feel of the show. This really sets a different experience for viewers.

When thinking about The Maniacs and their branding, I loved that they were focused so much on these things, even with what they wore during their shows. I decided I would stay consistent through a specific palette for the show that centers on the poster’s orange and green. Although orange is not a color I ever really liked, I have fallen in love with it. Right away you are hit with this color. It makes the show work.

ML: You began working on your Pendleton suits during your 2016 residency at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. What were your intentions for them originally, and how did you arrive at seeing these works as integral to The Maniacs exhibition?

WRS: Culturally, for the Crow Nation and for my family, Pendleton is so coveted. I have Pendleton suitcases, a coat, even shoes. Dating to 1904, the beginning of Crow Fair, Crow people only used these blankets for parading and to honor people. For funerals, the family members of the deceased give Pendleton blankets to the person’s loved ones. For a giveaway, when a clan gives a feast and they are feeding their clan uncles and aunts, if you give a Pendleton, that is pretty big. Or if you are a princess at a powwow, when you do your giveaway, you give a Pendleton. We keep the tags on the blankets—you see that in the early teens at Crow Fair.

With the Pendleton suits, I was thinking of them as the most expensive Westernized outfit that a Native person could wear. These are power suits for Native people, and eventually, I want to make a whole army of them. Right now, it makes sense for them to be part of The Maniacs faux concert stages with the instruments and all of that. The suits as audience members are really effective. This relates to the vibrancy of Crow culture—the saturation of color and honoring what the blankets represent. In the future, I would like to make more and have them placed in this spectator position.

ML: Can you talk about the materiality and function of the Crow flag in this exhibition?

WRS: I have used the Crow flag in several exhibitions now—at the CUE Foundation in New York, at the Triton Museum of Art in California, and the University Art Gallery in Las Cruces, New Mexico. What I am trying to do is signify the specificity of the Crow Nation and the Crow people. This is so important to me. I want audience members to know that what I am talking about is not pan-Indian. I do not know what it is like to be a member of another Indigenous nation.

My individual perspective and experience within the Crow culture is not going to be the same as even my father or grandfather’s experience. My perspective is specific in how I am moving through this body of work and when I am making works of different histories and timelines. The Crow flag grounds the space, with all of its symbolism and even the orange color in it.

ML: How does The Maniacs exhibition engage with your earlier works and current practice?

WRS: It is such a new body of work. I have lectured a few times about it and people respond by saying how different it is from my other work. But I do not think it is that different—it is a piece of the puzzle that has been missing from other work. I am literally making timelines now.

In earlier work, I researched the Crow Delegations from 1873 to 1880, and in those movements with those Crow ancestors, they were shaping what my reality is today. With this show, it is so much closer to what I know about how I ended up where I am and the experiences I am having. To me, The Maniacs artworks are very personal—this is closer to the fire than something that happened in 1873. I can see how the band’s experiences have molded me, my father, and my community. These are tangible things that I experience and learn about through this story of The Maniacs.

ML: How do you see this exhibition intersecting with the field of contemporary art?

WRS: In graduate school, I studied at UCLA with some of the most major, influential artists working today. I really love conceptual works. I love work where people are using images to tell stories or taking components of images and turning them into something else. And, with what is happening right now politically, the work I am doing is talking about aspects of history, race, class, economics, and how different people are living. To me, it is very much about some of the major issues going on right now. My work points out another side of the story—not the dominant side of the story. I am intersecting this space where artists of color are diving back into political and identity-based work, which is so exciting for me.

Wendy Red Star: The Maniacs (We’re Not The Best, But We’re Better Than The Rest) ran at the University Art Gallery at New Mexico State University from January 26-March 16, 2018.