Where Memory Burns: Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi

by Jade Barget

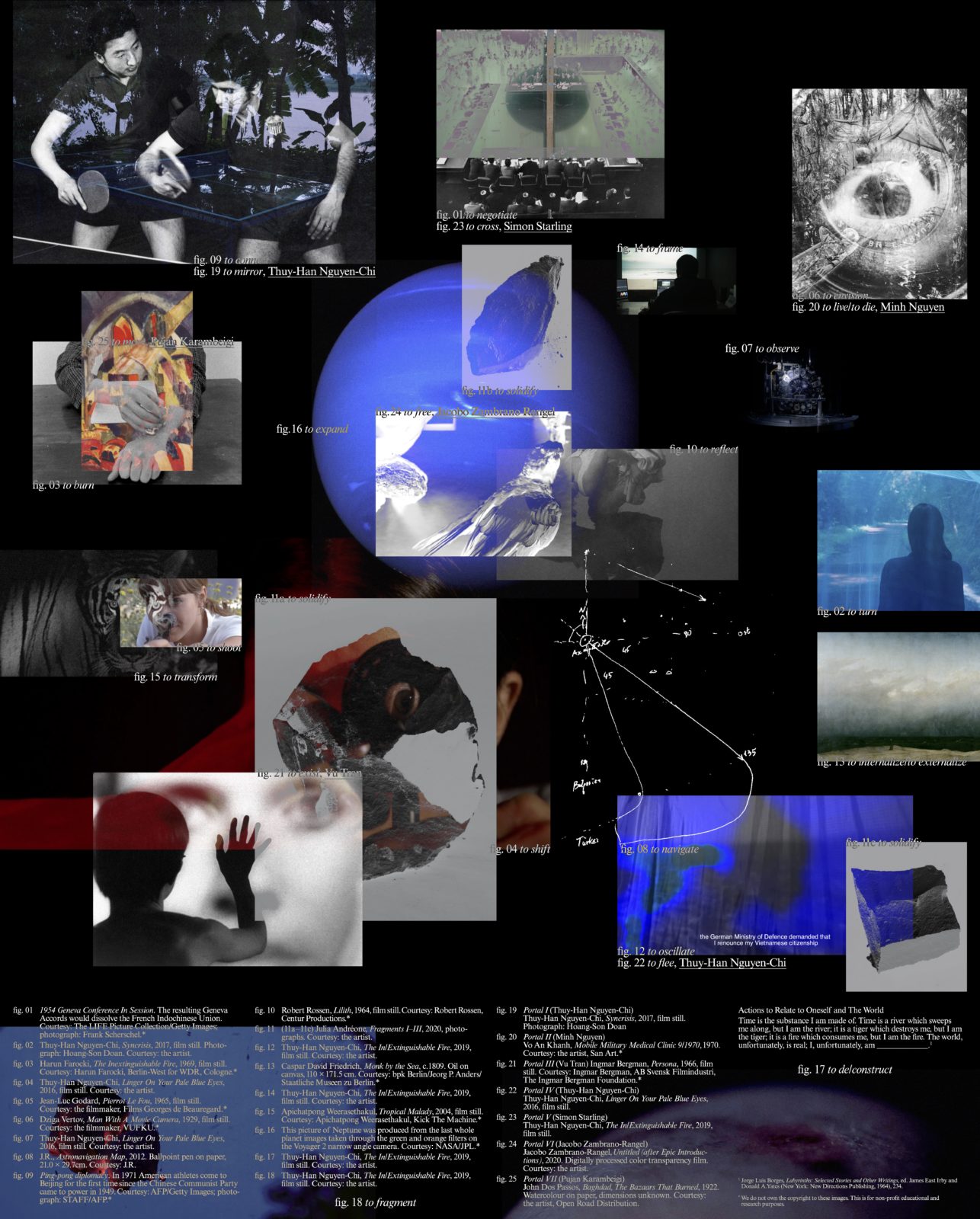

Image List: Actions to Relate to Oneself and the World (2020) by artist Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi is an online, dynamic atlas charting personal, historical, and cosmological territories simultaneously. In this system, inspired by Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, photographs, film stills, captions, and words collide and mesh.

Thinking in movement

Our view of Nguyen-Chi’s cartography is always restricted—we land slightly too close to see it whole. Unable to take a step back, zoom out, the viewer navigates eastwards, southwards, and inwards. As the cursor rests on images, they fade behind others, disappearing from view, flickering offscreen. When clicking, images are set in motion: visual portals lead to Nguyen-Chi’s films The In/Extinguishable Fire (2019) and Linger On Your Pale Blue Eyes (2016) as well as letters by artists, writers, and friends revisiting their encounters with the films.

There is a structure, but no direction. Neither a beginning or an end—viewers devise their own routes through the multitude of images. As vagabonds, we open tabs, read letters, watch Nguyen-Chi’s films, resurface and dive in again. Edouard Glissant’s notion of errance, or errantry,comes to mind.1 Errantry is drifting through, not knowing, in an effort to abandon existing systems of thoughts and preserve us from universalizing representations.

This notion of thinking in movement, in order to investigate the real, resonates within Nguyen-Chi’s practice. ‘To burn,’ ‘to expand,’ ‘to shoot’—in the atlas, she captions images as actions, illuminating the kinetics hidden beneath their apparent stillness. The experience of the work is one of restlessness—expanding into new significance, the images agitate thoughts and affects, developing and migrating across our screen-affixed vision. Indeed, migration is also the subject matter of Nguyen-Chi’s films: from exit to exile, from exile to exodus, the artist’s tales of departure are carried by the motion found in images. Movement is both methodology and substance.

Echoing Glissant’s errance, Nguyen-Chi’s thinking in and of movement is often concerned with negotiating dominant representations of history. Reflecting, amongst many other things, on how memories are formed and how cinema influences our sense of history, the artist complicates dominant narratives fantasized and crystallized by the imperial gaze. In questioning what influences collective remembrances of the past, of the deep and intricate relationships between cinema, memory and history emerge.

The darker waters of memory

Image List oscillates vertiginously across distant scales—from macro-history to micro-history; from Neptune to the eye. Photographs mark the beginnings, ends, but mostly the continuum of ideological conflicts between East and West exemplified by the Cold War. Time is fractured and reassembled, presenting itself in waves: opening up, stretching out, looping. It is the darker waters of memory we drift along, where temporality and space are unmoored and follow no linear progression.

While history is focused on presenting and representing events, memory inhabits them. Rigid definitions of past, present and future so necessary to history surrender to the simultaneity of recollection. Memory excavates sounds, scents, images and feelings, inconsistently diving in and resurfacing the past into the present. It is a volatile medium: it fades, like cinema, which Trinh T. Minh-ha, quoting Paul Virilio, speaks of as an experience of transience, an aesthetics of disappearance.2

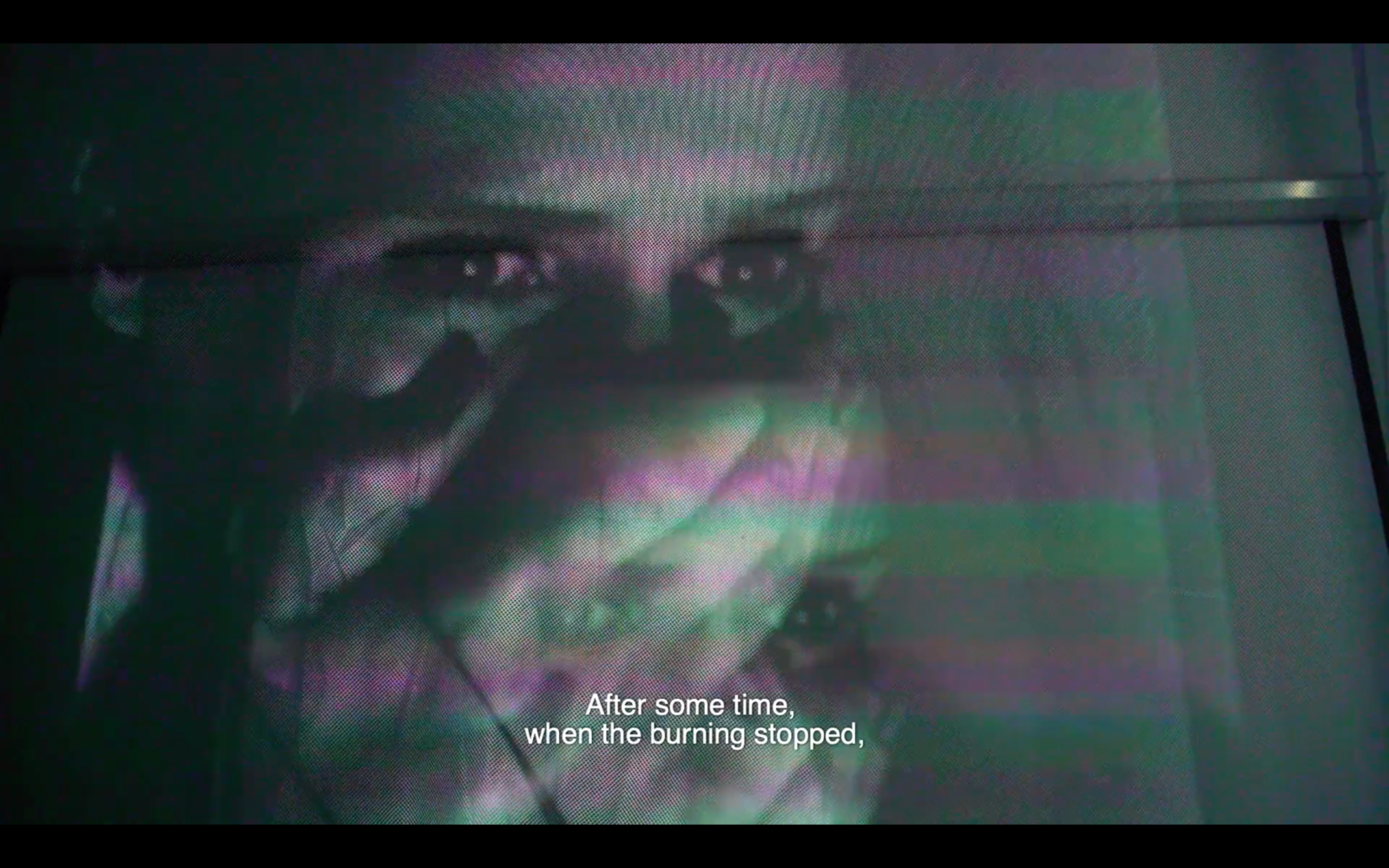

Cinema’s aptness for creating collective memories of historical events that viewers have not experienced firsthand is perhaps because it shares the transience of remembrance. Alison Landsberg, scholar of memory studies, speaks of ‘prosthetic memory,’ a phenomenon Nguyen-Chi investigates.3 Both ask us to question the sources influencing our remembrance of world events. The artist’s films infiltrate our memory with micro-narratives—in The In/Extinguishable Fire (2019), the artist’s father narrates personal stories of the Cold War era in Germany and Vietnam, while Linger On Your Pale Blue Eyes (2016) presents an inner monologue based on a friend’s experience of swimming at night in the Black Sea during her escape from East to West Germany in 1969. Lesser known pasts, lived and intimate experiences of world events, muddle the master chronicle to allow for complexity and nuance. History is highlighted as an ideological, cinematic, textual production.

Polyphony

In Nguyen-Chi’s Image List, many voices resonate. Alongside the voices of friends and family relayed by the artist are those of the filmmakers she quotes visually through film stills and the artists and writers who directly address her. In letters to the artist, Pujan Karambeigi, Minh Nguyen, Simon Starling, Vu Tran, and an anonymous person delve into their personal encounters with her work. Their voices live in the text through an epistolary style that is personal and named.

In For More than One Voice, the philosopher and feminist writer Ariana Cavarero acknowledges the silencing of the voice in the Western philosophical tradition, which she calls ‘the domain of a world that does not come out of any throat of flesh.’4 Cavarero argues that speech has been devocalized and abstracted to reach the soundless, universal dimension of thought preferred by the West.

Nguyen-Chi’s polyphonic approach to voicing memories allows the spectator to focus on the individual speaker, paying as much attention to the accent, tone, and timbre as to an idea or phenomenon. By doing so, Image List directs us to the subjective and uncertain, leading to the imagining of a narrative built upon unstable ground, soft and sentient. On this intimate plane, the artist resists a bodiless, singular conception of history; Cavarero’s ‘domain of a world that does not come out of any throat of flesh.’5

Within this site of instability, which perpetually exists in flux and reform, dominant discourses, knowledge sources, and power structures are hard to hold onto. The single telling of an event, the truth-seeking of a ‘real,’ is rendered hopeless. Rather than a field for the development and consolidation of history, Nguyen-Chi highlights the potential of cinema to become a space of attunement; to different experiences, different temporalities, different narratives. In the fog of remembrance, in our memories of events never experienced, we hear the voices of others in hers—a fragmented composition in the world.

Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi’s Image List: Actions to Relate to Oneself and the World (2020) is part of the online program Sets and Scenarios (June 15–December 15, 2020) an inquiry into our relationship to moving images in the post-cinematic context curated by Jade Barget, Angela Blanc, Panos Fourtoulakis, Sha Li, Yi-Ning Lin, Charlotte dos Santos and Lindsey Wiercioch, presented by Nottingham Contemporary and the Royal College of Art, London. Image List is designed and art directed in collaboration with Europium (Ghazaal Vojdani and Julia Andréone).

- Edouard Glissant, Philosophie de la Relation, (Paris: Galimard, 2009)

- Trinh T. Minh Ha, Cinema Interval, (New York: Routledge,1999), p.256

- Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014)

- Adriana Cavarero, For More than One Voice, Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), p. 8.

- Ibid.