Astrid Klein & B. Ingrid Olson: Profile of the Artists

by Alfredo Cramerotti

The conversation between writer Alfredo Cramerotti and artists Astrid Klein and B. Ingrid Olson took place during the preparation for the two-person exhibition at The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago in April 2017. Klein (b. 1951) lives and works in Cologne and Leipzig, and has shown extensively throughout Europe, Asia, and Latin America. B. Ingrid Olson (b. 1987) lives and works in Chicago and graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The conversation surrounding the dual exhibition—an intriguing pairing of practices that is particularly resonant and dimensional—touched upon themes of iconography and filmic sources, the performative potential of the photograph, and the dynamics of experiencing pictorial space.

ALFREDO CRAMEROTTI: Let’s start with the main ideas behind your respective work—I realize this is a big question, and of course I have my own reading, but it may not be the same with what you think are the main guiding principles of what you do. I am interested in knowing how you yourself ‘read’ your work. Can you step outside Astrid and Ingrid for a moment and let me know what you see?

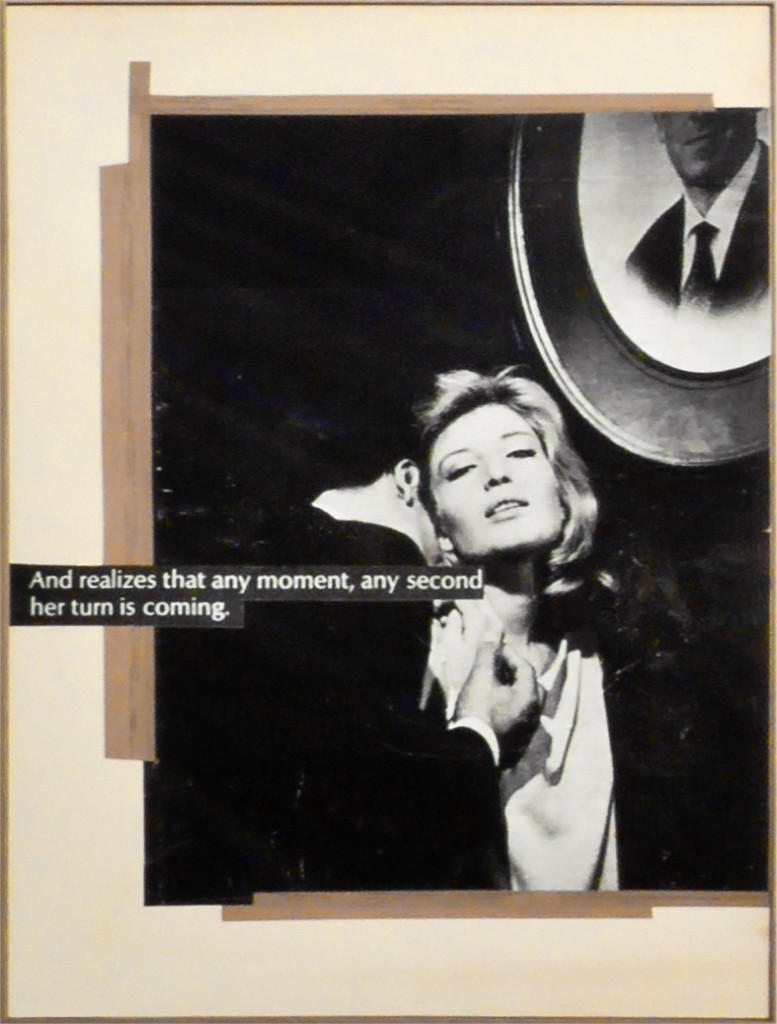

ASTRID KLEIN: This question cannot be answered outside of oneself—I would be equally hard-pressed to say there are any “main ideas.” I am interested in asking different kinds of questions. Text has been the defining pictorial element of my artistic work since the 1970s. The text works confront writing, and the material qualities of its reflection and affection. In this sense, typefaces are spatial structures; the written imagery of the printed word is always tied back to the sense of an arrangement to be read in space. Beyond painting and sculpture, I am influenced by philosophy, literature, music, and film—and of course the political questions and conditions of my time. My early reading included texts by Franz Kafka, for example, Albert Camus, Robert Musil, Antonin Artaud, and Samuel Beckett. I was also interested in the aesthetic theories of Walter Benjamin in combination with theories of perception and knowledge, along with neuroscience from the 1990s onwards. These sources flow into my practice in a fragmentary way—text and image are, for me, equivalent formal means that I use to develop my works.

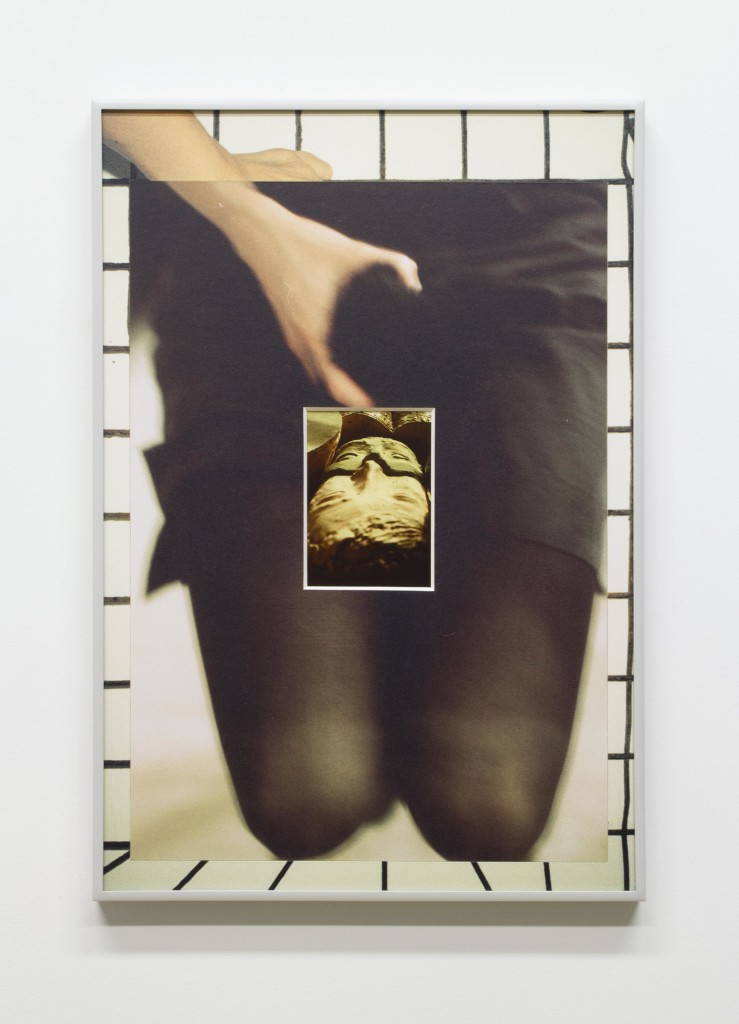

B. INGRID OLSON: Whether photographic or sculptural, I would say that much of my work questions the idea of being in a body in space. Ideas of embodiment, proprioception—the sense of oneself as a body moving in the world in relation to other things—gender, sexuality, as well as dynamics, such as universality versus specificity or inside versus outside, are all circulating in my mind as I make the work. Some references are explicit and completely intentional, while others are only latently available to me, though they still transfer into the work to some degree.

AC: Did either of you get any particular source of inspiration for the visual styles of the series you work in—for instance, the iconographic portraits ‘extracts’; the male gaze; references to visual culture; the tangibility of memories, etc.—or did they arrive in relation to the nature of the materials you have used, and locations (either physical, psychological or situational) you were positioned in?

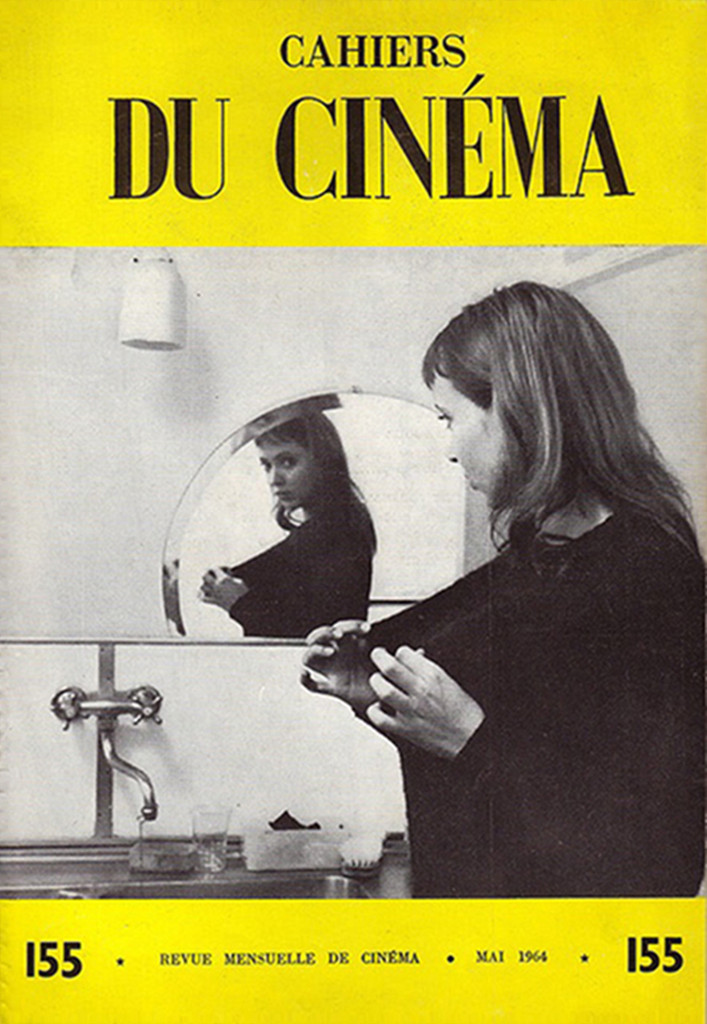

AK: Yes—just as my influences draw from various media, the source images I work with come from similarly different places. The iconographic portraits you mentioned stem from film journals like Cahiers du Cinéma, for example, the style of yellow press or photonovels. The typewriter works from the 1970s are, among other things, book pages that I have painted and written over. In these series, I have used my own writing, alongside literary sources—such as fragments from Zettels Traum (which translates to Bottom’s Dream) published by [German Author] Arno Schmidt, for example.

B.IO: Initially, when I started taking photographs, the gaze was on my mind. But, ultimately, this concept was not fulfilling in and of itself—I came to photography somewhat recently, after I graduated. It was not until I saw the exhibition, Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph, 1964–1977, at the Art Institute of Chicago, that I understood the potential of approaching photography through sculpture and performance. The artworks included in that exhibition used the photographic image more sculpturally, as a material document—whether framed, mounted, projected, printed—amidst other potent, specific materials. I clearly remember Michael Snow’s work in the show: a piece that had two large panes of glass, some sort of foam and a grid of photographic prints all sandwiched together in a very provisional way. The exhibition also featured many photographs that were not conventionally ‘good’ photographs, which I responded to. Technically perfect photography does not catch my attention as much as when something is supposedly wrong—blurry, under-exposed, strangely printed. Aside from the material treatment of the images, some of the artists in the exhibition were essentially performing for the camera, setting up constructed situations in order to be photographed. Thinking about performance documentation lead me to recognize the power that comes from being active, rather than passive, in front of the camera.

AC: Can you dive a bit into the technical aspects of the works? Such as the gathering of raw material, software or hardware (in the wide sense; they could be thoughts and bodies) used, as well as the selection and editing process? What are some of the particular challenges you (and your team, or the collaborators you work with) have faced in realizing the works? Where do you start from, and how do you proceed?

AK: I see myself as a sculptor and painter whose large-scale sculptural installations always incorporate the architecture of a given space as well. I have never tied myself to any one medium—exploring boundaries, both formally and in terms of content, is an important part of my work.

B.IO: I read for inspiration, take photographs using a simple point-and-shoot film camera, and work with fabricators to make structures to frame or contain the images and objects I make. I think delving any deeper into the particularities or difficulties of exactly how the work is made threatens to overtake the experience of the finished work with drudgery.

AC: Can you tell me about the relationship you want or aim to have with the viewer? Is your work basically a sort of a ‘gate’— although extremely subtle—which the visitor could go through, but also miss? Or is the viewer able to move from and to, around it—or beside it, or between it—but not really see it, or experience it from an ‘external’ point of view? Is the work meant to be ‘faced’ so to speak? What is the underlying approach to this relationship with the viewer?

AK: My work creates spaces that the viewer enters, where they encounter a world of imagery that they can walk alongside. In doing so, they become part of the art, the surrounding work and its fragments, which he or she perceives as an associative surface. A pictorial space develops between the work and the viewer. The viewer’s body becomes conscious of itself as a center of perception, a perception that sees itself as a continuum of ratio and sensation. In contrast to the visuality of the images in the work, the text element points to what is not yet visible—a movement that has been stopped, or is still undetermined, like a vibration that eludes visibility. Movement is also part of thinking, the walk along the pictures, but also the stilling of thought.

B.IO: My work has developed a particular style of invitation or implication, allowing for enterable or potentially empathetic vantage points. I think about the viewer’s vision as being compromised, taking on my eyes, or fitting into my spaces, and maybe creating something like a temporarily shared subjecthood. I consider this sharing of my vision and constructs—whether photographic, sculptural or architectural—to be generous, but also forceful.

AC: Tell me a secret about your work. Even a small one.

AK: A secret stays a secret. But I can tell you a motto: Can have anything, may throw anything away.

B.IO: I don’t make self-portraits.

Klein / Olson at The Renaissance Society runs through June 18, 2017.