The Inscrutable Laugh of the Other: Tala Madani’s Elusive Alchemy

by Vanessa Gravenor

Laughter, the antithesis of misery, can be an axe to combat ailments in uncertain times. One can note the emergence of a certain absurdity when censorship reigns and trauma weighs like heavy fog; yet, what to say of our current moment where nationalism thickens and financialization looms as the final reckoning? In her paintings, Tala Madani, Iranian-born artist living in L.A., blocks out an uncertain visual terrain attesting to the crisis of comedic impulses in current times. Her images are not parodies or clear caricatures, but instead simply a comedy of errors. Here the errors are generated within the images themselves, casting men as sometimes-Arab performing self-flagellation or women narrating their own oppression and taking pleasure in the process. In the light, one can see victims illuminated, acting out the dramatic relief while also digesting something akin to pain. In the absence of heroes, her work instead focuses on the chaotic mass of peoples that often are swept asunder. Shit, the material of pure degradation becomes the sole commodity people can barter, and in a trickster turn, Madani seems to use it as a way to both transgress and move forward.

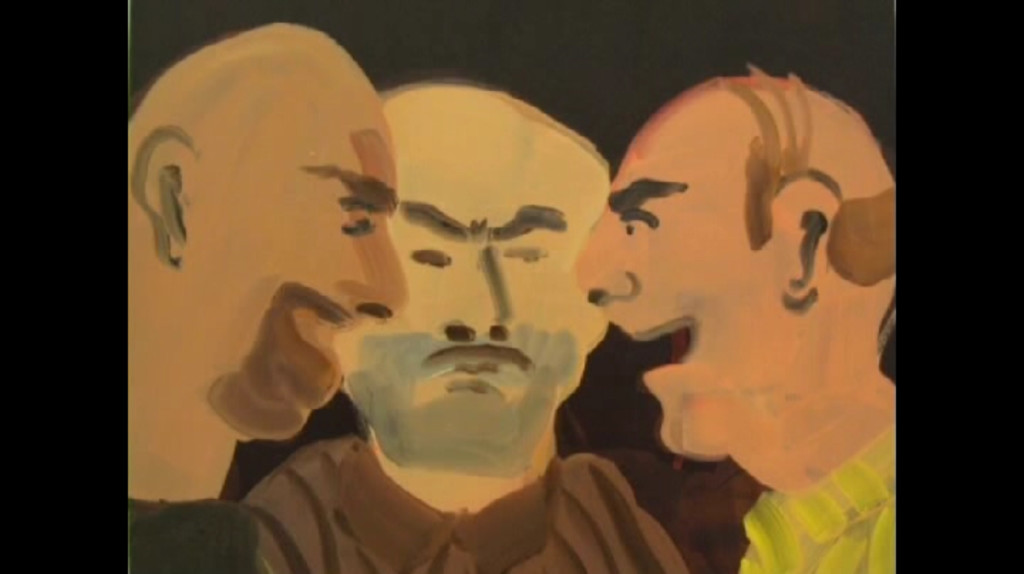

Madani’s paintings are hosts for different theatrical acts: man becomes animal, beast, devil, and debased objects before finally being conduits for illuminating the scene itself. The body is a passageway and also a crucible. The cold irony is that there is no single, clearly delineated, transformative event in Madani’s paintings – but rather visceral bodily responses such as vomit after an exasperated speech or a bodily ejaculation that turns into illumination. For instance, in ChitChat, 2007, the animation in MoMa’s collection that was exhibited recently in response to Donald Trump’s travel ban, shows two characteristically-Persian men facing one another in an argument. Their speech turns to violence, to shouting, and then to vomit. The animation is entirely silent but one imagines speech in the lack. Here, again, the only logical response to censorship or political violence is laughter, which isn’t just slapstick humor, but rather a break down language into babble.

Impishly hybrid, Madani’s paintings often portend disaster: not only the obvious one – our present political situation – but the patterns of thought that subtly inform it. The ugliness of eugenics, propaganda, and white supremacy all loom in crowded shadows. Dripping Flowers (2016) depicts a man, painted as a devil, positioned in an austere setting; his body is arched as he ejaculates flowers. Though ghoulish and charged with sexuality, their otherness is non-specific: lustful and foreboding caricatures neither quite American nor Iranian, neither modern nor primitive. The scenes resonate something of Artaud’s Theater for Cruelty in its insistence on an awakened subconscious to upset the audience into thinking, to identify with the devil, and to be ripped away from one’s own body. In Madani’s work, we see bodies rendered, performing barbarity and perhaps acting out socially assigned subservience. However, embodying subservience can also be a way to invert it, or in Rosi Braidotti’s terms, to uproot it. As Deleuze and Guattari explain in their essay “How to Make a Body without Organs,” in response to the priest setting desire in the East to designating the East as an unstable Oriental plane, the men of the east chanted “Yes, we will be your phantasy, your ideal and impossibility yours and also our own!”1 Somehow, in response to objectification and western power, the shortest route to overthrow it is to embody it and break things down into babble.

Embodying this under position, Madani’s animation Underman (2012), shows two smiling men dropping various objects on the head of a recumbent man. Each time, the objects break and the man is unable to get up or combat the assault. In the end, he seizes a hammer and drives himself into the ground. Through this senseless exploration of violence, Madani lightens her brutality with slapstick humor – and as spectators, our ethics also seem to liquefy. The title, Underman, recalls its diametric opposite in the Nietzschean term clumsily appropriated by the Nazis. The artist slyly inscribes the skewed mythology by simple vertical positioning. Referencing only the relative positions of under/over on the picture plane, the animation literalizes racial terminology as if to resist further perpetuating its violence. Like in Deleuze and Guattari’s comedic quip in response to power, sometimes literalizing the terminology designated by the West shows the instability in designation itself. It is not logical in the end for the man in Underman to hammer himself into the ground when he receives blows to his head, but of course, the blows to his head were meant to produce this self-inflicted harm. Emphasizing irrational gestures by responding in a similarly debasing manner can be the comedic axe that breaks the frozen sea inside.

Full of stock characters that play themselves, Madani’s animations invite us to watch persona’s that have wandered off from their own stories. Examining the characters Peter and Jane (2014), which referenced a set of 1960s educational books meant to teach language to children through cartoon image repetition, a new animation made for the Whitney Biennial, Sex Ed by God (2017), features an archetype persona of bestial femininity. The animation on a whole is a commentary upon pedagogical structures and how they are actual vehicles for power to replicate heterosexual structures. Similar to the tactics employed by Underman, Sex Ed by God features a disjointed humorous logic by replicating major narratives. Sexual education, meant to both civilize subjects and also quietly nullify their desire, leads also to an overtly sexualized construction of the young girl. In the case of the animation for the Whitney, this caricature grows and gains power through the alchemical transmutation of womanhood, objectified.

Madani’s images are devoid of messages, explicit agendas, or language (excepting a few grunts and sighs). In polemic times, Madani seems to champion the disavowed ambiguity and absurdity behind broad gesturing. Yet even while resisting didactic language, the Underman scene leaves clues about a series of events: a crime story, queasy with reverberations of old-world racial taxonomies and delusions of supremacy. Forsaking the soapbox, the debased figures laugh and add rubble to their pile of debris – taking what joy they can in their condition.