The Psychology of Painting: Dexter Dalwood

by Alfredo Cramerotti

The following conversation between writer Alfredo Cramerotti and artist Dexter Dalwood took place during the preparation for his solo exhibition at Simon Lee Gallery in London in March 2019. Dalwood (b. 1960 in Bristol, England) lives in London and has shown extensively throughout Europe, North America, and Asia. After a studio visit, followed by a number of emails and exchanges, the dialogue developed in sometimes unexpected directions: painting as thought rather than practice; generalization as key to unlock figuration; and the idea of ‘working against’ as guiding principle. And poignantly, it brought to surface the fact that, for Dalwood, recognizing the end of a work is what preoccupies him the most. Paraphrasing a music cultural meme, it is not where you are from – and not even where you are at; it is, rather, knowing when you are done.

Alfredo Cramerotti: I wanted to start with the main ideas behind your work—I realize this is a broad question, and of course I have my own reading of your work, but it may not be the same with what you think are the main guiding principles of what you do. I am interested in knowing how you yourself ‘read’ your work. Can you step outside Dexter for a moment and let me know what you see?

Dexter Dalwood: I am first and foremost interested in painting as a conceptual practice. When I say this, I mean the meta-awareness of painting as language: the detached, yet figurative, use of form as language. It has taken me a long time to get to this position. But it is what engages me in still wanting to make paintings at this point in time. In answer to your question, when looking at my work and trying to step outside of it—I think I see disparate images bolted together like words in a sentence that make up a whole.

AC: Did you get any particular source of inspiration for the visual styles of your series of works—for instance, the iconographic ‘non-places’ series; the absence of people; the ‘oblique’ gaze; the tangibility of memories, etc.—or did they arrive in relation to the nature of the materials you have used, and locations (either physical, psychological, or situational) you were positioned in?

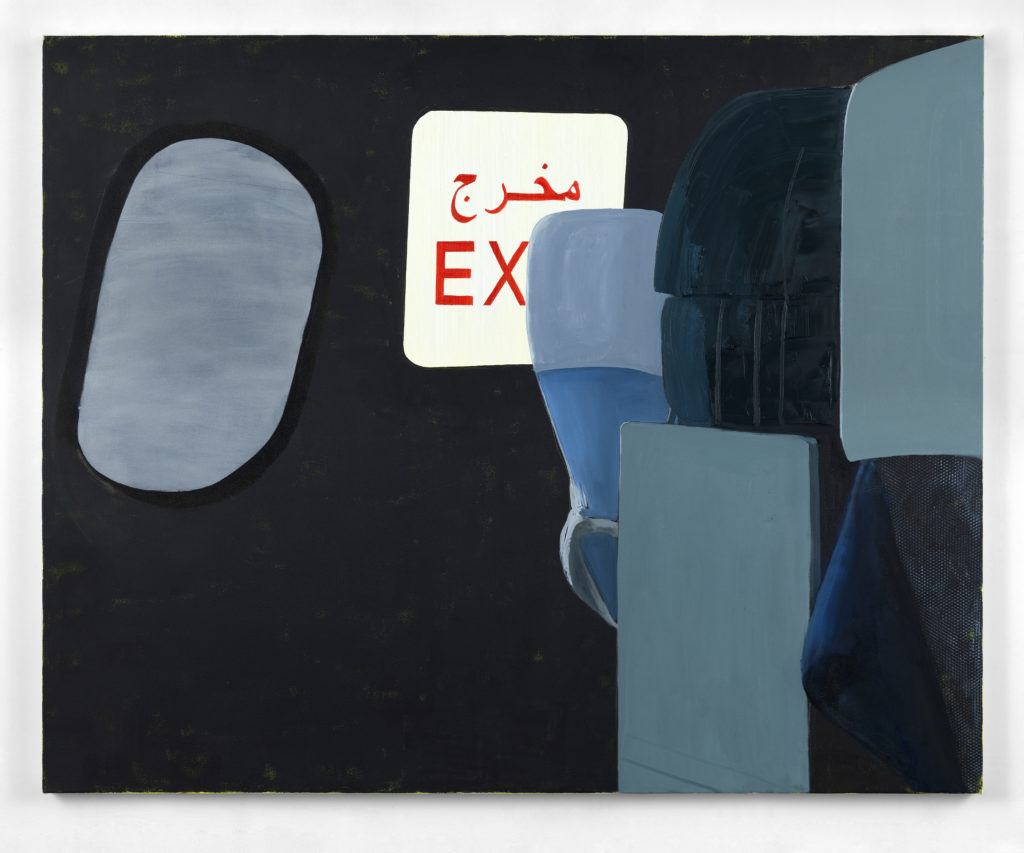

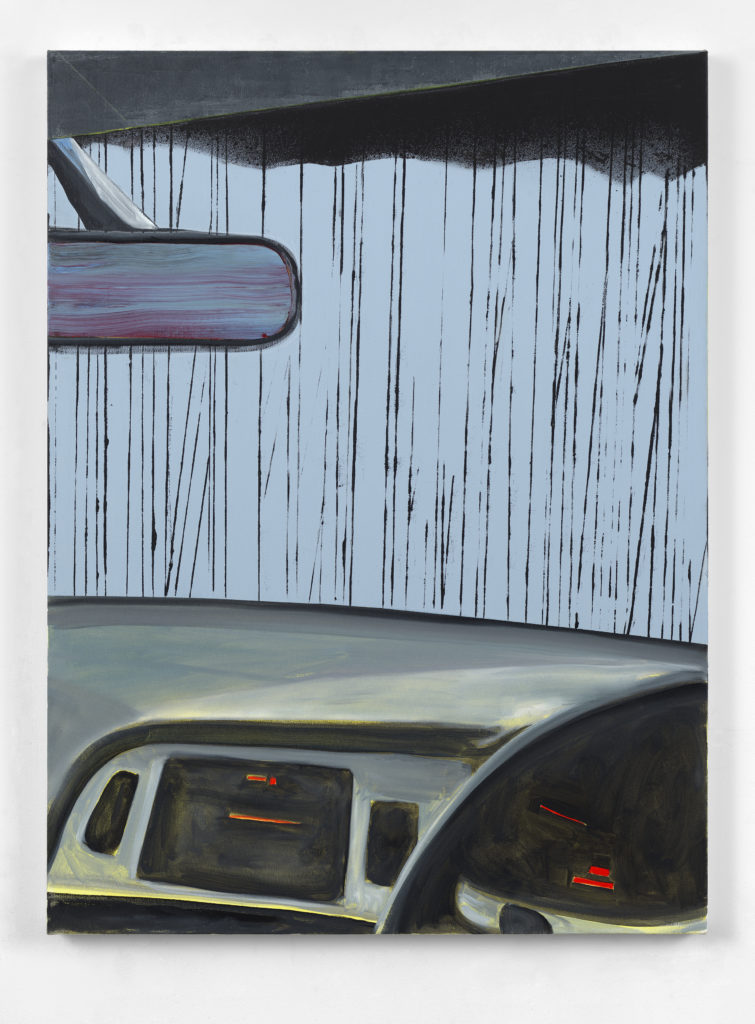

DD: With this recent series of paintings, I was thinking of going back to the source of several early modernist paintings. I was particularly thinking about Van Gogh, an artist that has never been particularly important to me, who used the formal language of Japanese prints to create a drawing style with more economy. I was looking at some of these prints by Hiroshige and was not interested in the drawing style but the use of ‘generalization’ in figuration. I mean the simplification of the depiction of something like rain or snow. The visual style of this series started from this point, and as a way of painting an assumption of something—not unlike a label, saying ‘here, this is rain,’ or ‘this is snow,’ etc. That was the starting point. How the paintings formulated had to do with seeing these elements from within the enclosed space of a car, an airplane, or a corridor, all of which lead to a prevailing mood that was somehow psychological.

AC: Can you delve into the technical aspects of the works? Such as the gathering of raw material, software or hardware (in the wide sense; they could be thoughts and bodies) used, as well as the selection and editing process? What are some of the particular challenges you (and your team, or the collaborators you work with) have faced in realizing the works?

DD: When it comes to painting, the answers can become very ‘painter nerdy’ as they are about the use of paint, etc. To be brutally honest, in this series, I liked to set up something to work ‘against.’ I had often put down a ground color of neon yellow, and then spent a lot of time at the beginning of the painting trying to get rid of it—this is to do with ‘beginnings,’ and trying to just start a painting and make decisions from there on in. Earlier in my work, I would always begin with a collage, but now I prefer to start with one or two elements, and then begin to make decisions in front of the painting. The editing process has to do with the judgement of when something is ‘enough.’ What takes a long time in painting is knowing when something is ‘enough,’ and most importantly, when something is finished. I have never worked on a painting and then walked away and thought, “It’s finished.” It just comes down to realizing— after perhaps two or three days—that it is no longer preoccupying you or screaming out for attention. Then, after a longer period you realize it is done.

AC: Can you tell me about the relationship you want or aim to have with the viewer? In your opinion, could the visitor go ‘through’ the work, but also miss it? Or is the viewer able to move from and to it, around it and beside it, but not really see it—or experience it from an ‘external’ point of view? I am thinking in particular of the “on-places” series. Is the work meant to be ‘faced’ so to speak? What is the underlying approach to this relationship with the viewer?

DD: I do not think of my work as a ‘gate’ that the visitor can go through. I think of the viewer when making paintings, as I am also thinking of myself as a viewer of the painting. When I am looking at a painted surface, the question I ask myself is “What do I want to see now?” I hope that the viewer also thinks that when looking at my work. The question is: does it engage them and also resist being consumed for a Nanosecond? If it does, and they do not dismiss it, then the process of my work for a viewer is one of looking and thinking about what is in front of them. If that process begins, then in some way my job is done.

AC: Tell me a secret about your work. Even a small one.

DD: Due to a knife cut, my blood is mixed into the red of one of these paintings.