Through Smoke and Across Dissent: Power Plays with Perfumery

by Matt Morris

The earliest culturally organized uses of smell were based in Ancient religious activity in Egypt, through the burning of fragrant sacrifices and aromatic smoke for purposes of divination (indeed, the word ‘perfume’ comes from Latin, meaning ‘through smoke’). Across centuries and global regions, perfume (as with painting and its burgeoning art history) serves as a tool for power—passed from churches to governments and enjoyed by upper classes. The conception of ‘bad smells’ brought together early scientific theories around animal survival instincts compounded with persistent superstitions that associated sulfuric smells with damnation. In the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, rank classism assigned smells deemed most foul to the bodies and lives of the poorest citizens. Xenophobic tendencies against “foreign stenches” in Rome at its height of power presaged the later pernicious ways that racism was stoked by widely accepted misinformation about the inferior body smells of people of color.1

Suffice to say, the stakes around control over one’s own smell far exceed discourses around beauty and pleasure; scent has long been used as a tool of ideology, social regulation, the performance of identity, and economic might. A significant turn toward the practice of modern perfumery as we encounter it today was the abolition of apothecary and perfume guilds in France in 1791 during the French Revolution, and with them the governmental controls around what class of person could be a perfumer and what products they were permitted to produce. Amidst the rise of capitalism and industrialization, perfume shifted in the nineteenth century to become a commodity par excellence—a confluence of the artistic expression of the perfumer and the evolving trends of consumer predilections. As new, more cheaply produced synthetic ingredients became available near the start of the twentieth century, production costs dropped; perfume products became more accessible to lower-income consumers; and profits boomed. Estimates vary, but on average the global fragrance industry’s worth in 2018 was measured at 60 billion dollars. And that industry reaches far beyond those glittering jewel-like bottles on display in department stores: one would be hard pressed to find any corner of manufacturing or any component of our lived environments that have not been scented.

It is within this complex politicized history, alongside the staggering influence of scent across industries and cultures, that the use of perfume by contemporary artists is so compelling. Any overview of these artistic projects should pay devotion to Rrose Sélavy, Marcel Duchamp’s gender-bending alter-ego who spectacularly released her own celebrity fragrance in 1921, simply by buying a popular department store perfume and collaging a new label onto it. The following century witnessed notable collaborations between artists and perfumery: in the 1930s and 40s, surrealists Leonor Fini and Salvador Dalí designed flacons for the fashion house of Elsa Schiaparelli; Dalí would later join a growing list of artists who have released perfumes, among them Niki de Saint Phalle, Andy Warhol, and Anicka Yi. Perfume houses have likewise taken inspiration from the art world, with scents inspired by art galleries such as Andrea Maack’s Smart (2010); Memo Paris’ Marfa (2016); Roads’ Art Addict (2017); and Comme des Garçons’ Serpentine (2014), named for London’s famed art venue. Complimenting these art-inspired fragrances are many contemporary artists who have come to utilize scent in their work in order to test the veracity of how bodies, identity, and social systems have come to be defined.

Clara Ursitti has pioneered new ways of engaging audiences with scent for more than twenty years. Propelled by inquiries into the ways contemporary life is conditioned by gender, sexuality, commercial brand identities, war, and even the assumptions that designate humans as a species,2 Ursitti’s practice includes video, installation, sculpture, and performative interventions. Across numerous projects, her deft incorporation of scent triggers deep psychological and emotional responses. In a recent email exchange, Ursitti reflects, “Reactions to scent are extremely subjective. You cannot talk about it without reflecting on your own subjective position, as there are no words dedicated in most Western languages to describing odor sensations. So, for example, we can describe a visual sensation as yellow, red, etc. …It is trickier with odors. We rely on our subjective experiences to describe them (e.g. it smells like coffee, or it reminds me of being at the dentist) or crude dichotomies of good and bad.”

In many works, Ursitti develops blends of ingredients that recreate a body’s odors, and at other times incorporates mass-produced commercial perfumes as readymades. For Jeux de Peau (Sketch No. 1) (2012), she used one of each: two identical carmine red blown glass bottles are presented side by side. In one is a decant of the 2011 perfume Jeux de Peau released from the niche French perfumery Serge Lutens; the name of the scent means “play on skin,” and it smells of burnt toast, apricots, and milk, among other foodie notes. Working from the name of the scent, Ursitti filled the second bottle with a scent she blended based on a skin analysis. Comparatively more challenging, this blend possesses a shocking blast of cumin-like sweatiness and a very animal musk. “I find it interesting that our taboos and conditioning around body odour lead us to often find something that is naturally more offensive than something that is artificial. What does this tell us about our relationship to our body when this is the case?”

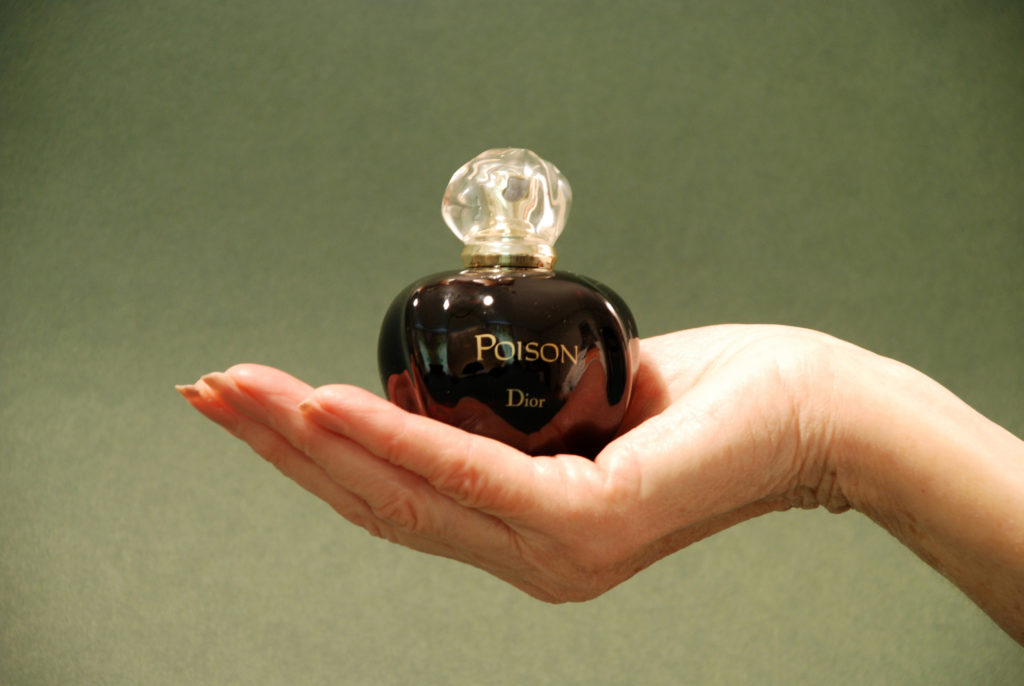

Among Ursitti’s most striking works are a series of social interventions that she has collectively titled Air Play. “These works have three ingredients,” Ursitti explains, “A fragrance, a demographic, a social situation.” In Poison Ladies (2013), Ursitti invited twenty-five women, most over the age of sixty, to attend to an art opening wearing Christian Dior’s Poison, a fragrance released in 1985, notorious for its pronounced potency and huge fruit-and-flower composition. In the 2007 work Mesmerize, a young man arrived at an art opening smelling “of the sea—salty, slightly fecal, slightly fishy.” In these and similar projects, Ursitti experiments with the social perceptions and latent eroticization of older women and a young man augmented by particular scents wafting around them. A heady density of perfumed air usually associated with a boutique like Sephora settles over the dynamics of art world socializing.

In 2013, Rotterdam’s Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art saw Sands Murray-Wassink in the nude, standing before a pair of glass cabinets packed with perfume bottles of varied sizes, designs, and vintages. He was performing his work It’s Still Materialistic, Even If It’s Liquid (From Me To You) (2013) at the invitation of artist-publisher-mystic AA Bronson as part of a sprawling exhibition of queer and feminist artworks Bronson had curated. Across his bare torso, the words “ACCEPT–ANCE ART” were painted in blue. Throughout the piece, Murray-Wassink offered perfume consultations to gallery passerby, fashioned like an empathic variation on the typical perfume counter clerk. As in much of Murray-Wassink’s work, this interactive performance was expressive of an emotional potential for connection. The artist considers this a form of sociality, “When I sniff with other people, be they salespeople or perfume friends, I find myself reveling in the fact of being human and sharing an open secret that we are all organic and ‘smelly’ as people. It is a bit abject, and also something I am thinking a lot about, because much of my work is blunt and gross and messy and not meant to be beautiful at all, and then there is this counterpoint of beauty in perfume. Because blinding floral beauty is usually what sweeps me off my feet.”3

The perfume flacons from which he sampled are all part of an artwork Monument to Depression, ongoing since 2004, which now comprises more than 500 different bottles. After a six-month period of hospitalization for depression, he says, “I started collecting perfume, just buying what I missed, and loved, things I was not allowed growing up, any perfumes marketed to women.” As with his paintings, performances, book projects, and web-based forays into writing perfume reviews and compiling lists of feminist artistic influences, Murray-Wassink’s formidable perfume collection surges with affect oriented toward the difficulties of navigating a world defined by gender, misogyny, vanity, and alienation. A self-described “beauty warrior” and progeny of an abstract expressionist greatgrandmother, a Freudian psychoanalyst grandfather, and poet father, Murray-Wassink’s art proceeds from a rich interior life that blurs daily activity into studio work, “I have started to describe myself as a perfume collector and body artist (performance, writing), but the perfume always comes first, and my work is not about visible things—it is about emotions, relationships, feelings, behavior.”

When Aleesa Cohene’s background in found footage video work brought her to Cologne to work with artist Matthias Müller, she was introduced to 4711, the first Eau de Cologne, popular for over 200 years, since the times of Napoleon. Cohene recalls, “I was working on Like Like, a piece about these lovesick people in a relationship with one another,” she explains, “And I decided one of the characters should smell because there was a repetitive smell so pervasive in Cologne.”4 Like Like (2009), is among the multi-channel video works Cohene has conceived for gallery installations that remix appropriated film footage into narratives of queer desire, tense psychotherapeutic sessions, and scenes that track the gendered and racial subtexts of received social scripts. “There were a few pieces where I asked myself what I can take from the story and amplify in a space, and have us live in that world even deeper. Scent is a really good way to hold someone in place and transport them at the same time.”

Working from the fragrance notes in the citrus and herbal composition of 4711, Cohene created a new scent that used more or less unusual modern scented materials like Lenor “April Fresh” fabric softener, black pepper, juniper bark, and fibers from security blankets. The scent was diffused from behind one of the video monitors, thickening the atmosphere of the room that was painted in green-blue stripes matched to a porch swing’s fabric upholstery seen in one of the video’s clips.

Many of Cohene’s projects are based in what she calls an “associative parlance,” where one piece serves as source material for the next. You, Dear (2014), for instance, is a pile of onyx grapes that give off a scent based on dialogue from the preceding video Hate You (2014). A young female client speaks with her dream analyst, asking if she is ever noticed that bunnies smell like ass. As she speaks, the therapist begins to eat—first a grape, then apple, then pear. The resulting scent is built from that fruity bouquet and Cohene’s associations to the soft furriness of a bunny and the smell of a clean ass.

After years of scenting spaces and objects for her video installations, Cohene is currently in the process of developing versions of three of her previous formulations to be released as wearable perfumes. And as with Murray-Wassink’s own tempering of beauty with other worldly concerns, while Cohene finalizes these perfumes, she has also embarked on a research project into the potential development of antidotes for scent-based weapons, particularly those used to control and suppress protestors. “Pepper spray is more pervasive, but I am more interested in the skunk spray. It is really, really cheap. It is made with a yeast compound. There is a neutralizer out there for people who work in disasters and cleaning up dead bodies, protecting themselves. Or, even more, the police and military who are using this spray. Of course, this neutralizer was made for them and not the victims of it.” In exploring what form such an antidote might take, she discovered what products are currently available, “What exists on the market I find kind of precious, which is a lip balm that goes above your lip. It just cancels out the smell for you. So, if you are covered in it, you still stink, but you do not sense it. My interest is in the exact opposite of that: I am interested in what it might mean to neutralize the air—conceptually and chemically.”

Questions of how scent has been commodified, weaponized, and positioned at the thresholds of some of our most intense emotional associations run nimbly through these artists’ research. Working against singular reliance on the visual, as fraught as it is with encoded cultural assumptions around identity, fragrance presents a potential for diffuse, excessive, and even contradictory associations. The forms and displays of artworks often neglect their function within systems of economic exchange. Given its history of classism as a signal of luxury, perfume is used by these artists with curiosities and critiques built into the formats of their work. In recent years, growing concerns about chemical sensitivity has heralded many versions of “scent-free” policies—the city of Halifax adopted a public policy against the use of personal scent in 2009, and since then, museums, offices, and contested public spaces around the world have instituted similar regulations. With note to the argument that these measures are in the interest of public health, the implementation of such policies are not neutral and often disadvantage workers whose cultural backgrounds are characterized by fragrant cuisines, religious practices, and home lives that are not easily appreciated or assimilated into mainstream (read: white) American social space. Indeed, the use of the concept of “freedom” from scent here is especially charged, enacted as it is alongside mounting xenophobia in the United States and abroad. Ursitti’s modes of intervention and infiltration, Murray-Wassink’s emotional labors, and Cohene’s investigations into the radicalized interpersonal valences of bodies and their scents all represent efforts to counter conformity as a mechanism of social control. Tinged with queerness, plunging into the throes of beauty and revulsion, these olfactory artworks propose ways by which we might venture, as if through smoke, beyond the constriction of our current political age.

- Much more on this dark chapter of scent can be found in Jonathan Reinarz’s remarkable essay “Odorous Others: Race and Smell” in Past Scents: Historical Perspectives on Smell, University of Illinois Press, 2014.

- My sincere thanks to Lydia Brawner for introducing me to Ursitti’s practice.

- As shared in an email exchange with the author.

- As stated to the author in a phone interview.