Tourism, In Passing: A Series of Vignettes

by Naoki Sutter-Shudo

We might never again live in a world with a real belief in permanence. The advent of thermodynamics and its accompanying concept of entropy, has given us the modern knowledge that chaos unavoidably prevails. No system is stable. Still-life paintings, based on actual witnessed scenes— whether seen live or photographed—pretend to possess this air of permanence, as they fix a fleeting moment down onto canvas, panel, or paper. Flirting with realism, yet never fully committing to it, five of such works invite tales of speculative sight-seeing.

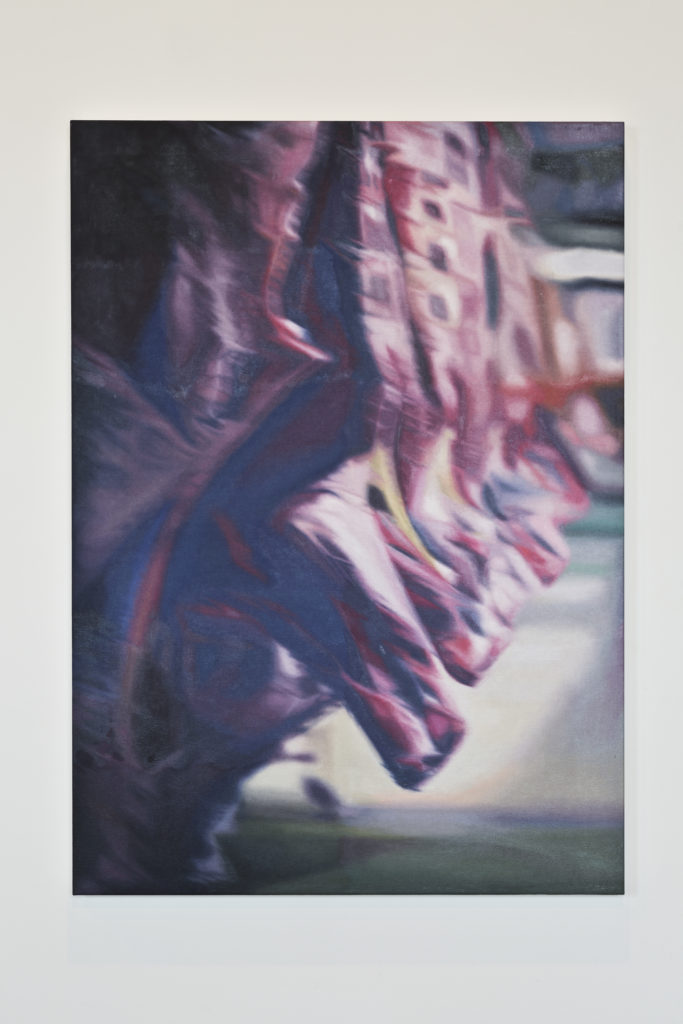

ALAN MICHAEL, Train in the Snow

The spongey piece of bread, riddled with holes, seems to scream out its refusal to be consumed; this is not what the man imagined when his wife asked if he wanted toast. The bizarre food is called a crumpet: in between a pancake and a muffin, its vile design appears as an aberration. Certainly, it is incomprehensible how anyone would choose it over the myriad of bread types in the history of humanity. He thinks very strongly he does not want to eat it, and it strikes him that the situation is one with no winner. However, filling the crumpet’s pores with jam muffles its pleas of not wanting to be eaten; it is quite good in the end. At least this ridiculous little bread has a firm stance on its destiny as food, whereas most have no opinion. A stance of refusal that beautifully aligns with that of this man. In contrast, he does not even notice the little birds on the branches outside of his windows: they sing, but not about wanting or not wanting to be eaten; in fact, he does not think of them as food, neither do they consider themselves edible. Sometimes, the man eats, with great satisfaction, that which wants to be eaten. Gustatory advertisements whisper to him, and yell in many voices—the man recognizes and chooses the one that knows his tone and mirrors it. The man could go for some hearty piece of meat, one echoing the diet of its living origin—like acorns fed to pigs, like good grass fed to a cow, coming through with boldness, from a dry aged beefsteak. Add to that little shallots, and a reliable red wine. And evidently, potatoes. What a nice meal the cattle accomplished. After dessert the kids will go to bed, as the adults continue their praising of the cow.

Alan Michael (b.1967) lives and works in London, England. Recent exhibitions include Jan Kaps (Cologne, Germany), Christian Andersen (Copenhagen, Denmark), High Art (Paris, France), Galeria Zero (Milan, Italy), CAC Vilnius (Lithuania), Galerie Gregor Staiger (Zurich, Switzerland), Vilma Gold (London, England). Upcoming exhibitions include Frans Hals Museum (Haarlem, the Netherlands).

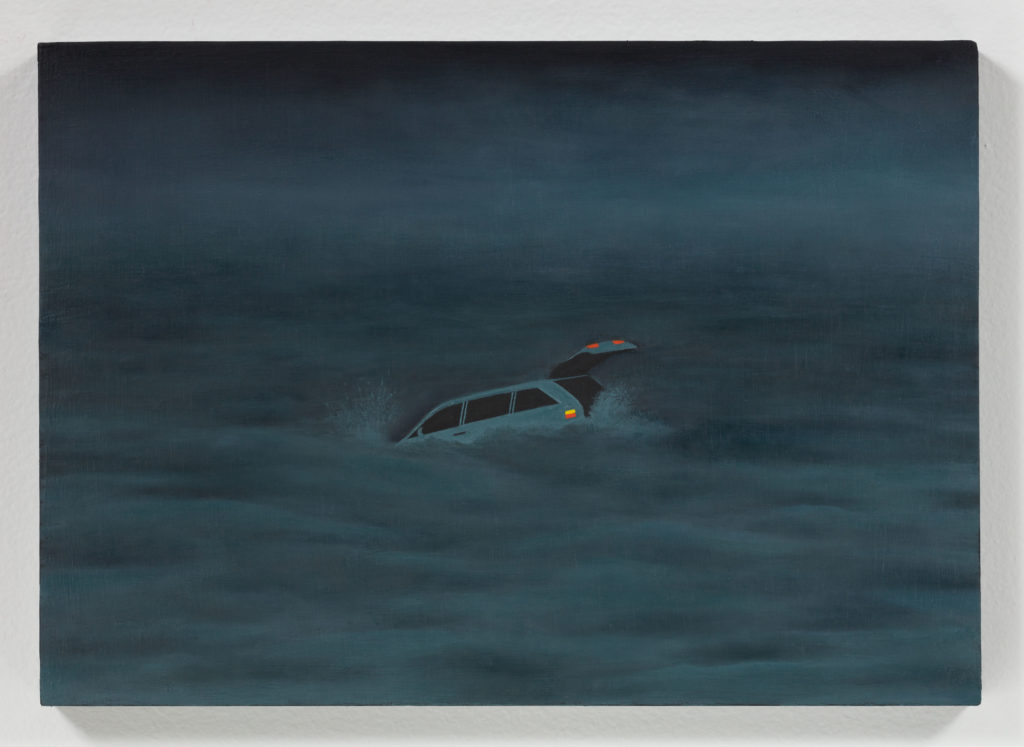

ALEXANDRA NOEL Ship Spotting

In a universe irreversibly cooling down, some things remain warm: the first tears of a newborn, the last meal on death row, and the headlights of three cars gliding on the freeway at dusk. Like the ecstatic eyes of the Wise Men fixated on the rising star, rushing to worship their new king. However, one of these cars takes an early exit to another route—the harmony breaks. Such a selfish action contributes to the impossibility of new miracles happening spontaneously, and should be seriously punished. And really, what looks like a star in the distance is merely a surveillance satellite: unconcerned, cold, distant. Had the freeway been gifted its own free will, it would surely use its focus to reassemble the Wise Men. Instead, all it can do is send insignificant bugs flying into the windshield; little yellowish specks that constellate upon the view of the driver. Not to worry, the car’s wipers are brand new, and effortlessly erases the hundreds of tiny cadavers with a simple flick of the driver’s finger. A shame, for they made the vista less tedious than the foggy gray expanse outside. The driver is looking for the ocean. Contained within her car, which is itself contained within the massive freeway system, being shot from bifurcation to bifurcation, even the idea of reaching an ocean seems unreasonable. The children in the backseat holler out of boredom: just wait and see what wonders they will soon witness, wonders that their underdeveloped brains cannot comprehend, yet already know to fear. The repair of the decaying infrastructure had been deferred: continuing would certainly mean arriving at cracked roads, fallen bridges, interrupted viaducts. Perhaps only then, by accident, a leap into a sea of calmness would be possible; the car able to drift away peacefully would slowly lose its heat, finally united with the world.

Alexandra Noel (b.1989) lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Recent exhibitions include Freedman Fitzpatrick (Los Angeles, CA), Travesia Cuatro (Guadalajara, Mexico), Shane Campbell (Chicago, IL), XYZ Collective (Tokyo, Japan), Bodega (New York, NY), and Balice Hertling (Paris, France). Upcoming exhibitions include a solo exhibition at Parker Gallery (Los Angeles, CA), and a solo presentation with Bodega at Frieze London.

2018. Oil on canvas, 14 x 11 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Bureau, New York. Photography by Dario Lasagni.

CALEB CONSIDINE Untitled

Assisted suicide supports a three-generation family in this modest apartment. Administering doses of relaxing decay via drips, the elderly death practitioner also keeps an eye on his grandson and his friend watching TV in the same room. The patient lays on a relatively new futon (less than ten have died on it), and the obligatory wearing of diapers keeps the sheets unsoiled. She glances at the mute TV. The soundtrack is a CD she has provided, but the delicate details of her departing tunes are muffled on the cheap stereo, and the heat forces the AC to be on full blast, especially since the shutters must be kept closed. What is happening should not be too public, and the streets are riotous. Meanwhile, the kids are hooked on the show—on the screen, a little robot keeps itself busy, while repeatedly smoking everything within the allowance of a few packs of cigarettes. The robot goes to sleep once it has consumed them all, until it wakes again. Its movements are nervous, its torso dusty with ash. An overarching presence (the exact sentience of this being is left uncertain within the narrative, but unnecessary to qualify here) is constantly selecting souls to either save or damn, supplying fresh dread to whomever watches the plot unfold. The being slowly becomes weary in its continuous task. Ubiquitous and infinite, it glides with no effort and no end, yet there is less and less grace to its motions. It recycles saved souls into cigarettes for the little robot to smoke. The children debate what will happen to the damned souls: Who is allowed not to try? Would you fight for salvation? The grandfather tells them to lower their voices. The CD plays on repeat and is well into its second cycle, yet the noise of the street still overpowers it. A gray veil starts to tint the patient’s vision, followed by a red one. She closes her eyes: darkness until further notice.

Caleb Considine (b.1982) lives and works in New York, NY. Recent exhibitions include Bureau (New York, NY), Galerie Buchholz (Berlin, Germany), Massimo de Carlo (London, England), Essex Street (New York, NY), Greene Naftali (New York, NY), Aishti Foundation (Antelias, Lebanon), Metro Pictures (New York, NY), MoMA PS1 (New York, NY).

LOUISE SARTOR Sicilian Lovers

Burdens, such as the château, with its ample grounds and its various architectural follies, had been sold off long ago. Centuries back, men and women, old and young, had assembled to carve, polish, and paint what visitors from villages near and far had come to marvel at. Obviously, the death of a few workers was inevitable—a square zone of contrasting vegetation could once be found where the corpses were laid, a few minutes away from the obligatory stable. Each of these spaces were demolished efficiently. What the people really craved was not majesty or glory, but fresh, clean water, unsoiled by human contact, sleeping deep under these lands. The gardener would have a maid go and fetch some from the well to fill vases of delightful seasonal blooms for the Lady of the house. None of the above-mentioned occupants left children. The well crumbled. The rediscovered underground water was bottled by local entrepreneurs and sold in high-end grocery stores, shipped in the same trucks that had formerly transported the contents of the château prior to its bulldozing. Auctioneers scattered the chandeliers, trophies, and portraits, which now occupy a network of tasteful interiors that collectively cover more territory than the original grounds, yet this imprint is smaller still than the web of the bottled water consumers. A dainty silver frame, originally held within the château chambers, now holds a photograph of an absentminded poodle, inside of the water bottling factory. Or is it of a human child? The dust keeps collecting so as to blur the outlines of the image. If you have binoculars, you can see, from the factory’s windows, some feral dogs fighting each other, where the well once was. They run around and dig up bones to gnaw, and fight to dominate the terrains. But the ruins beneath them are not their own; they were built by the skeletons the dogs now consume. Of course, the windows need cleaning too. It is advised to exist humbly, keeping in mind that you are merely being allowed to live.

Louise Sartor (b. 1988) lives and works in Paris, France. Recent exhibitions include Bel Ami (Los Angeles, CA), Crèvecoeur (Paris, France), Château de Versailles, Paris de Tokyo offsite (Versailles, France), Ghebaly Gallery (Los Angeles, CA), Galerie der Stadt Schwaz (Schwaz, Austria), Musée des Beaux-Arts (Dole, France), and Fondation d’entreprise Ricard (Paris, France). Upcoming exhibitions include Gwangju Biennale, Palais de Tokyo Pavilion (Gwangju, South Korea), and Frieze London with Crèvecoeur.

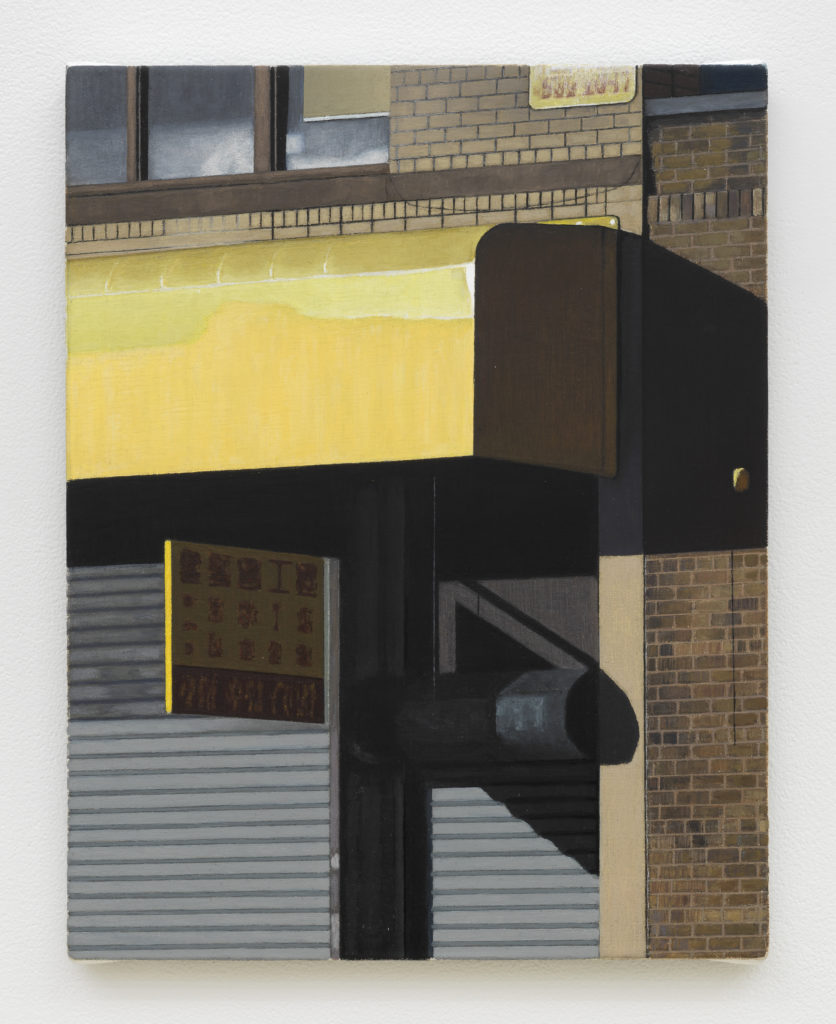

ORION MARTIN Asleep in a Fish Can

Unbeknownst to the war at large, the seaside town stays at peace. Geopolitical and cultural conflicts have not trickled down to the desolate place protected by these dense woods; similarly, painless modern methods of killing lobsters, such as electrically stunning them to render them unconscious, have not yet reached the region, which will continue its traditions of throwing the crustacean into water that is heated until it reaches its boiling point, transforming the animal’s shell from blue to vermilion. Later, buttered onions accompany the feast, cut in bulk by the cook’s apprentice. As the knife dulls after slicing and dicing pound after pound, the onions, crushed rather than cleanly cut, discharge a white milk; the apprentice weeps from the lachrymatory effusion. He sometimes cuts his fingers and contemplates the red blood upon the white milk, while recalling the lobster’s blue blood. The presence of copper is what tints the blood blue; the apprentice notices that the onions’ peels also have a coppery hue. The idea of inevitable death (his, everyone’s) is too offensive to the apprentice in these moments of moronic reflections: he knows nothing about the lobster’s longevity or its natural habitat, only how they should be prepared for consumption. He wonders who would know about his own biology— his death, followed by the recycling of his flesh into a meal—if that were even an option. Clearly, the idiot should focus on his cooking skills instead of daydreaming unsolvable considerations. Is he a total cretin? The hungry diners in the next room, whose only want is to fill their stomachs before going to sleep, should be served as quickly as possible. After all, the possibility of a rogue missile annihilating the town, the result of some miscalculation in a military office hundreds of miles away, is not to be neglected.