Whatever Body: Commodity Limited // On the Surface of an Image

by Vanessa Gravenor

A coughing man on repeat stares forward. His beady eyes have a hollowed-out effect and inform us, the viewers, of his irritation with our presence. The footage of this man, who is called The Assistant, hacks into a very specific exhibition methodology in contemporary art: the critique of capitalism by way of its aesthetic. The piece is produced by Paris-based art collective Claire Fontaine—comprised of two artists, Fulvia Carnevale and James Thornhill, who are branded as the collective’s assistants—for their exhibition The Crack-Up (2017–18) at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (NBK) in Berlin.

The work is, of course, part of the very critique it produces, and is representative of many post-conceptual artists, who work with the detritus of the commodity and advertisement images that lie under capitalism. Adopting the language of the oppressor in order to be heard has long been an emancipatory tactic, reaching its precipice in the 1980s with appropriation art. Yet today, with the current hegemonic state of images, whose back-lit displays clutter banks as a means to advertise expedited transactional spending, the forms of representation inherited from this culture often act as disembodied phantoms who have little to do with life, or the suffering that their dissemination only accelerates. When stepping into a contemporary art gallery, why does one have a tingling sensation that they have seen these images, these bodies before: on the walls of a Citi Bank? And if so, why have these emptied bodies been brought to the galleries, in lieu of the very human bodies who are compromised by the immaterial ones?

As contemporary art appears to have inherited the aesthetic of these specters of capitalism, its capacity for critique is limited. Realizing this limited value, artists such as Ewa Partum and Sanja Iveković have embodied this flatness in order to explode space, while others like Sondra Perry and Hank Willis Thomas have drawn attention to the history of the advertisement industry’s adaptation of black bodies. Others offer an ironic twist of aesthetics, such as Claire Fontaine, John Miller and Takuji Kogo, and Irena Haiduk, to point toward the fascistic reign of the flattened image in contemporary life.

We begin with Claire Fontaine. Their name comes from the popular brand of French stationary, making the artist’s name a linguistic ready-made. As Anthony Hubermann surmises, Claire Fontaine intends to create a “human strike.”1 This act is distinct from the art strike or the boycott, but certainly calls attention to the inherent brokenness of the art system. While in The Assistant (silent) (2011), we see a white man coughing on repeat, it remains questionable if this man experiences prejudice or disenfranchisement. In the end, the main question that we can ask ourselves when looking at the work is: where do we situate identity politics when it comes to contemporary art’s critique of commodity fetishism?

When speaking about images and advertisements, we do not speak about human bodies, but as Giorgio Agamben explains it, a “whatever body” that has been split between its appearances—both particular and generic.2 This is the body that Claire Fontaine intends to criticize. And yet, when building this whatever body, there is often a very real correspondence to reality and human communities, which are abstracted in advertisement and pornography.

In the same vein as Claire Fontaine, John Miller and Takuji Kogo’s exhibition Open to All Ages and Ethnicities, also on view at NBK in 2015, presented their characteristic slapstick critique of commodity culture by way of appropriation and redaction. In one of their videos, part of their series A Little About Me (2010), a teenage girl holding a camera is seen rotating—clipped, still images of her body float above and through a Walmart parking lot. The sound, an auto-tuned voice, speaks what seems to be a Craigslist personals listing. Miller and Kogo self-profess their work to be about “highly commodified zone of romantic love.”3 Because of the highly commodified nature of their source material—life as we know it— their work is also aesthetically and emotionally flat. This work can be read through Tiqqun’s manifesto Preliminary Materials of a Young Girl, which marked the body of the young girl as the production site for the dissemination of Capitalistic dogma. This body, as characterized by Tiqqun, is both a victim and a perpetrator of violence—she takes on the poses of advertisement, becoming a figure that hijacks and is hijacking. Ironically or not, most artists who critique commodity culture recall this figure in order to demonstrating a complex relationship with power. However, though this figure fits into the “whatever body,” its multiplicity is lost through its generic nature.

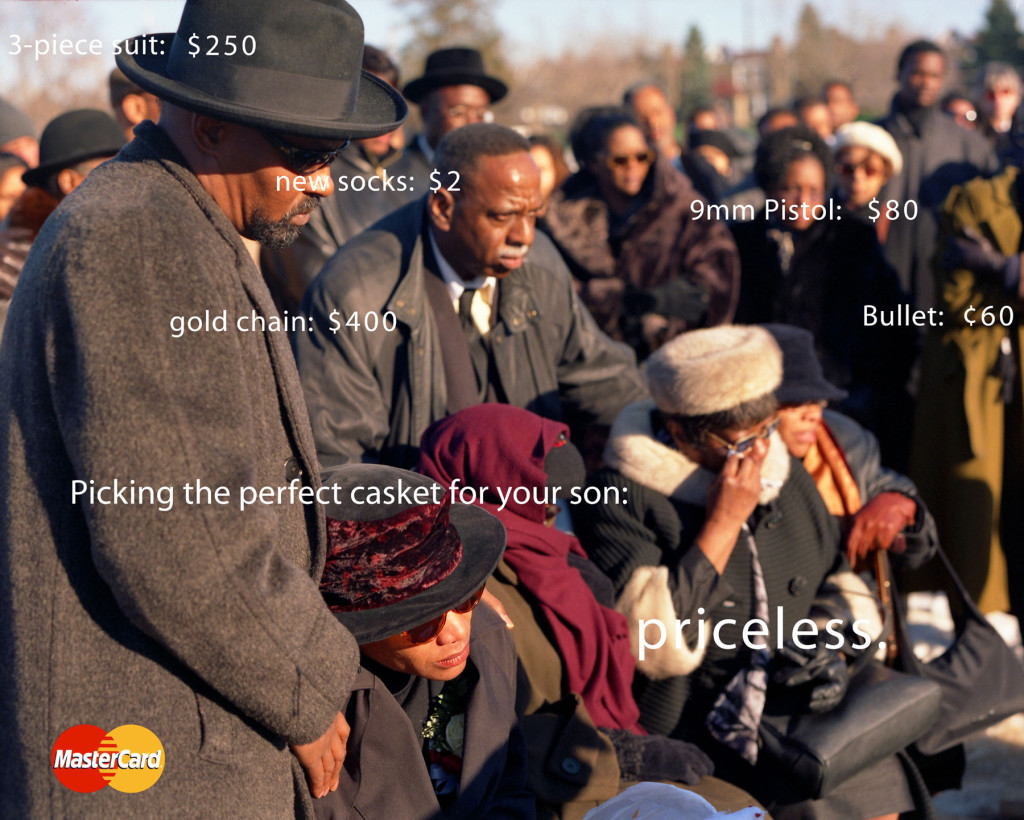

As a counterexample of hacking corporate aesthetics, Hank Willis Thomas’ series Branded (2003) examines the explicit violence within the advertising image. In his pieces, black male bodies are seen with Keloid scars in the shape of Nike logo, drawing attention to the utilization of blackness as cultural capital for sports brands. In her book Dark Matters, Simone Browne explains how the placement of Thomas’ Branded Head (2004) in light boxes next to real corporate institutions, such as J.P. Morgan, called attention to the fact that these banks put out insurance policies on slaves.4 Though Thomas certainly uses these corporate aesthetics, they are meant to draw attention to the bodies that have been appropriated by the florescent glare, yet also return agency to the subject—calling attention to the hypocrisy evident in the system of production.

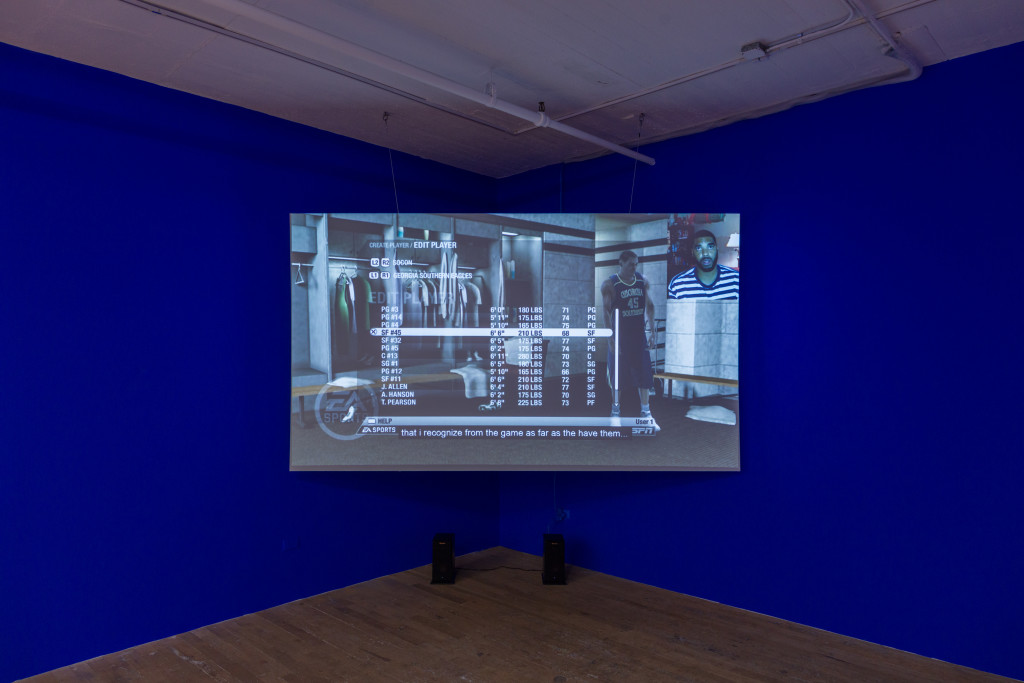

Similarly, Sondra Perry’s It’s In the Game (2017) examines how her brother’s body was appropriated for a basketball video game. While on a scholarship to play college basketball, Perry’s twin brother’s image was literally stolen and transformed into a three-dimensional rendering, to which he was not compensated for, nevertheless informed about. This action harkens back to the theft of dead black bodies throughout American history, as historian Harriet Washington discusses in her book Medical Apartheid. Because slaves did not have rights, these bodies were long used through the nineteenth and early twentieth century by doctors to be practiced upon for dissection. In Perry’s video, one can see this practice being carried into the virtual sphere of the video game.5 Using CGI, Perry examines how the material black body is re-commodified in the digital world. Relating to Thomas’ Branded series, Perry’s It’s in the Game shows another field for capitalistic violence on the body.

Speaking from a Soviet and post-Soviet context, performance artists Ewa Partum and Sanja Iveković have based their careers on critiquing the system of aesthetics and images that produce oppression and violence. Ewa Partum, a Polish performance artist who began working in the 1970s, examined how her own body was the main salable entity both on the social and art market. In her performance Change (1974), performed in Łódź, Poland, she invited makeup artists to age part of her naked body— emphasizing how one part of it, the young part, was the side that inevitably fetched more value in the gallery.

Similarly, Iveković, the same generation as Partum, has specifically used advertising material in her work as a feminist artist and activist. Her project Women’s House (Sunglasses) (2002–2004) was a collaboration with women who suffered from domestic violence. In her offset prints, advertisements from Dior are placed alongside names and stories of these battered women. In a conversation with art critic Katarzyna Pabijanek, Iveković writes for ArtMargins: “I appropriate media images because my intention is to subvert the assumptions implied in the discourse of the mass media using its own language.”6 Here, we see the same tactic of subverting mass media language through its own use, however, there is a transparency in the process that signals to bodies who are otherwise invisible under the dominant image of a single woman.

It is perhaps here that we depart from Agamben’s body to instead mark the whatever image—one that is produced under capitalism. Though, it is paramount to remember that for former socialist countries, the whatever image of the advertisement was introduced through a violent revival of the capitalistic system.

Such is the case with Belgrade and Chicago-based artist Irena Haiduk, with her project Yugoexport. Yugoexport demonstrates a critique of capitalism performed in a similar vein as Claire Fontaine—yet it speaks from a post-Soviet context. In her work, the woman is featured as an emptied-out proxy for hypercapitalistic structures. This erasure and leveling of the woman can be seen as an aftermath of the dual roles woman had to take on in Yugoslavia, tasked as both workers and mothers. Haiduk instead produces her own commodities in the form of ergonomic factory shoes, entitled Borosana Labor Shoes, through her piece Nine-Hour Delay (2012– 58), which are then sold to the audience and function as post-conceptual ready-mades. Here, the commodities are explicitly part of the capitalist system—when one wears the shoes, they become part of the “army of beautiful women” posited by the artist.

The process is one of deep metaphorical violence, as viewers transform into emptied-out performers. In Yugoslavia, as Keti Chukhrov explains, the woman’s question posed by feminism was seen to be solved by socialism, and was conflated with the problem of private property.7 One can then see that there are many ironies present within the Yugoexport project—the notion of the worker is sold to the audience as a form of private property (both in the form of the object and as a certificate of authenticity), whose result leads back to the disenfranchisement women.

These current post-conceptual practices that utilize corporate aesthetics occupy a place of deep ambivalence. By appropriating the aesthetics of hypercapitalism, the works are founded on principles of alienation, with the hopes that this antagonism will emancipate their spectator. However, often times, it is the disconnection from the affected communities at hand to whom this violence is founded upon that cannot be seen in the final image. Often, the sexy image matches the production of Deutsche Bank or Citi Bank. The reason for this equivalent production value has two functions: first, to make a sort of second imitator that could reveal uncanny truths lost and hidden within the sleekness of an ‘official’ image, and secondly so that these objects can be competitive in the art market. Works such as Iveković’s, who uses advertisement aesthetics as activism to bring to light domestic violence, or Thomas’ Branded series that draws attention to the commodification of black suffering, effectively channel the negativity of the fascistic image produced of—and for— capitalism in order to shift the focus back onto suffering.

However, when the work falls into a fictional space, it begins to mimic the whatever body, therefore losing its capacity to reflect. Instead of enacting change, representations of flat models, often idealistically white, act out a well-known script. It is because advertisement images often are meant to mask reality—such as the working conditions of Amazon, versus their outward appearance—that when the signifier of the repercussions on real life is missing in contemporary art, the result is as violent as the hegemonic original.

It seems necessary to redeem an embodied sense of thinking and knowledge, especially when confronting images that borrow techniques from billboards or luxury branding. Perhaps the language of advertisement has appeared too much within the sphere of the gallery, so much so that the matter of the body—that being life—has been compromised, becoming instead something like a hysteric simulacrum.

- In an interview with Claire Fontaine for Bomb Magazine, Anthony Huber man explicitly states how the collective self-professes empty aesthetics to profess a “a subjectivity that gets rid of itself.”

- Agamben, Giorgio. The Coming Community. Tr. Hardt, Michael. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 2007.

- A Little About Me: Four Works by Robot (John Miller and Takuji Kogo), Online Exhibition at the New Museum

- Browne, Simone. “Branding Blackness: Biometric Technology and the Surveillance of Blackness.” in Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham and London: Duke U, 2015. p.126

- “The Restless Dead: Anatomical Dissection and Display” in Washington, Harriet, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial times to the Present, Harlem Moon: New York, 2015.

- Katarzyna Pabijane, Women’s House: Sanja Ivekovic Discusses Recent Projects (Interview). Online, Dec 2009.

- Chukhrov, Keti, “In the Trap of Utopia’s Sublime: Between Ideology and Subversion,” in Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe, ed. Pejic, Bojana Mumok: Vienna. p.23