Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go: Almine Rech

by Paige Landesberg

The presence of text in artwork challenges the set of definitions that we have for words in favor of image. Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go, recently on view at Almine Rech in New York, the exhibition depicts a history of words used in artwork, from early modernism through to contemporary. Words printed on a page or in a book have an air of authority; they are given more credibility than image, while images themselves are often deemed subjective. Several artworks in this exhibition counter this idea, including Bruce Nauman’s neon piece, None Sing/Neon Sign (1970). Nauman pairs two phrases that contain the same set of letters, but have possibly no significance as a pair in their definitions, demonstrating that words can be interchangeable visual symbols existing in endless scenarios. The piece illustrates the arbitrary nature of truth in a word’s relationship to its definition, pointing to the fact that text plays a visual role as itself, completing an image or idea.

Traditional application of text on a page relates to pre-modern painting; its content offers a representational narrative—as a sign that points to a specific significance. However, the presence of text in artwork is also a departure from narrative representation, as words gain flexibility to take on a range of meanings. In artworks, words, as both materials and subjects, carry the potential to shift from being direct signs to instead transforming into pictures, objects, or symbols.

It should be noted that the works in this exhibition represent a Eurocentric lens of art history that can only be viewed critically and acknowledged as incomplete. Nevertheless, the exhibition reveals how several artists of different generations employ a multitude of strategies that question the role of letters, words, and numbers in artwork. Positioned in conversation with each other these works tell a story of the gradual departure from representation that emerged and is consistent throughout modern and contemporary art.

The early Schwitters and Picasso works from 1910–1920 on view maintain some level of representational narrative through their allusions to objects depicted. In Picasso’s drawing, Still Life with Newspaper (1923), we see fragments of the word “journal” across rectangular shapes that function both to reference the image of a newspaper, and also to create texture through hand-drawn type. Many of the early modernist works in the exhibition, such as this, are positioned next to the work of post-war artists, such as Ed Ruscha and Jasper Johns, where words operate similarly, despite being made at radically different times. In Ruscha’s Steak (1962), the image of a steak with chunky, capitalized red letters spell out the word—like in the Picasso, the word both references the object in the picture, and also serves an independent purpose of evoking a tone through the unique typeface. In this case, Steak references masculinity and mass-produced food packaging that was pervasive in the 1960s.

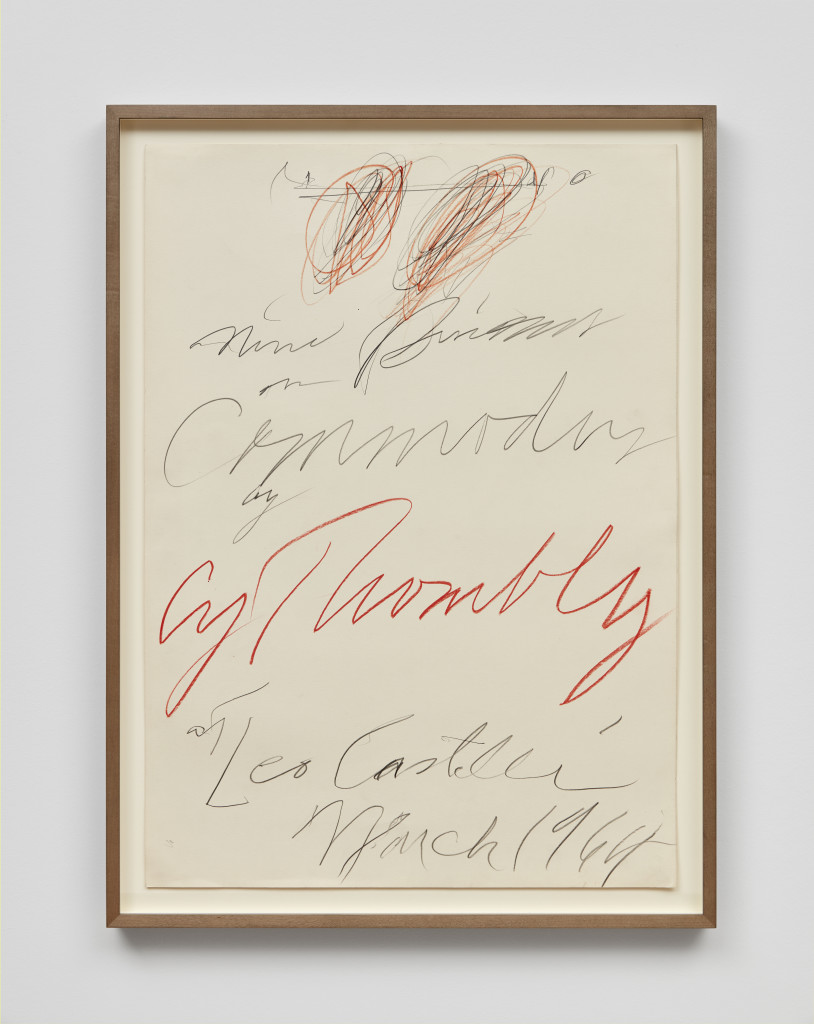

In Cy Twombly’s work Drawing for ‘None Discourses on Commodus by Cy Twombly at Leo Castelli’ (1964) the text’s content is only significant when using the title as a guide; on its own, the hastily scribbled pencil marks are barely legible, and transform into the realm of abstract line-drawings. Similarly, Alighiero Boetti’s work Senza Titolo (1980) continues to stray from using text to reference existing signification, as he uses scattered punctuation marks, letters and numbers to create seemingly random patterns. Here we begin to see a departure from the initial mode of using text to allude to depicted objects or narrative in the artwork.

Castelli’ , 1964, Colored pencil and graphite on paper 27 3/8 x 19 5/8 inches, Photograph by Matthew Kroening, Courtesy of Almine Rech Gallery

Magritte’s La Trahison des images (1952), a drawing of his famous The Treachery of Images (1929) painting which declares “Ceçi n’est pas une pipe,” translating to “This is not a pipe,” contextualizes the conceptual text-based artwork that followed it, supposing that the image and text are not synonymous with their commonly understood significance; declaring the divorce of the sign and the signified. Kosuth’s work, Four Colors Four Words (1966), Robert Morris’s Location (1973) and Sol Lewitt’s A point which is located halfway (…) (1973), which came thirty plus years after Magritte’s painting, offer new iterations of this idea by utilizing text as information or prompts, rather than just as texture, pattern or style. Four Colors Four Words is a colorful neon sign that describes itself in its text. Location has adjustable counters that represent the numerical distance in feet of the work from the ceiling, walls and floor where it is installed. A point which is located halfway (…) is a drawing in which the only image is the handwritten description of where the text itself lies situated on the page. Kosuth, Lewitt, and Morris’ artworks use text in conversation with form to define space both inside and around the work. For example, while we often encounter neon signs outside of a bar, or a convenience store advertising a product, or indicating the shop is “OPEN,” Kosuth’s sign, unlike others aesthetically similar to it, refers specifically to itself as a beginning and an end. It is a sign referencing its own significance as an object.

These works, much like Magritte’s La Trahison des images, demonstrate a sense of self-awareness or reflexivity that is inherent in conceptual art. Asserting their presence in the room by referencing the space they take up, each of the works challenge the viewer to complete the image with an understanding that the artwork holds more meaning than what it gives away. Avoiding metaphor in favor of literalism, the works require the viewer to both accept the words’ content as truth and simultaneously look deeper into their significance in visual art contexts, as subjective images.

The Pop Art movement gave artists permission to produce imagery that is void of content altogether as a critique on mass commercial culture, text notwithstanding. Within this exhibition, Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box (Soap Pads) (1964) borrows the visual language of mass-produced objects to produce iconography—in classic Warhol style, and artists such as Martin Kippenberger and Mario Schifano use similar techniques to appropriate universally recognizable typefaces, as the image of a brand or consumable personality.

Several women artists who are left out of this exhibition, such as Jenny Holzer or Adrian Piper, have challenged the commodification of text by reclaiming it as representational in contemporary art, often portraying direct, confrontational statements to viewers. Unavoidable political narratives where the text refuses to be merely aesthetic continue to emerge in protest of the mainstream Eurocentric art historical narrative. Unfortunately, this nuanced discourse is excluded from Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go, as we only see one artwork made by a woman, Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (You Kill Time) (1983), out of the forty artworks represented in the exhibition.

Throughout the history of modern art, and through the present, we see text extend further and further away from its written meaning as it becomes consumed as image. The title of the exhibition, Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go, inspired by the title of a massive Ruscha painting that is the centerpiece of the show, is originally a line excerpted from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, spoken by King Claudius in Act III. The full quote reads, “My words fly up, my thoughts remain below. Words without thoughts never to heaven go.” (Shakespeare, 3:3:4) Portraying the disconnect between the displayed word and its meaning, the quote outlines the alienation of the signified, as our culture continues to grow densely saturated with visual content. While this continues to ring true, the chronology of this exhibition ends with the most recent piece being Kippenberger’s Don’t Wake Daddy VII (1994), twenty-four years ago. With the rise of social media and emerging modes of interdisciplinary art practices, how do we experience text today in artwork and visual culture outside of the gallery? Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go presents a thorough survey of how the use of text in artwork has evolved throughout modern art, but we are left itching to address the global contemporary relevance of this topic today.

Words Without Thoughts Never to Heaven Go at Almine Rech Gallery, New York, ran until December 16, 2017.