From Print to Negative, and Vice Versa: Mladen Bizumic

by Alfredo Cramerotti

The following conversation between writer Alfredo Cramerotti and artist Mladen Bizumic took place during lunch in the leafy garden of a restaurant in the Museum Quarter of Vienna, in June 2018. It just preceded the preparation for a group show at the Society for Projective Aesthetics!, a Kunsthalle-like exhibition space and program which was the brainchild of the late gallerist and curator Georg Kargl, with whom the artist had a close relationship.

Alfredo Cramerotti: Let us start with the main ideas behind your work: I realize this is a big question, and of course I have my own reading of your work, but it may not be the same with what you think are the main guiding principles of what you do. I am interested in knowing how you yourself ‘read’ your work. Can you step outside Mladen for a moment and let me know what you see?

Mladen Bizumic: I see myself as an image maker. As opposed to the today dominant way of digital image making, the vast majority of my images are physical objects printed on paper, mounted onto Dibond, and framed behind the glass. Needless to mention, image making has been around since the beginning of humanity. Yet the fact that I often use a medium format film camera is a significant footnote. More closely, my work is about the issues surrounding the nature of photography as it shifts from analog to digital. I see this activity both as related to the history of image making, and as a continuation of my own personal biography marked by all the people, institutions, and services that I previously or still work with.

AC: Did you get any particular source of inspiration for the visual styles of your series of works—for instance, the Kodak series, the Picture in Picture series, etc.—or did they arrive in relation to the nature of the materials you have used, and locations (either physical, psychological or situational) you were positioned in?

MD: The KODAK series started around 2012. I was shifting to my new studio and packing up my Kodak paper, film negatives, and slides; the Eastman Kodak Company was all over the news. The 131-year old film pioneer that has been struggling for years to adapt to an increasingly digital photographic world, filed for bankruptcy. Some films that I was using were discontinued or replaced with more generic versions.

But the source of inspiration for me was the story that I came across accidentally. According to Steve Sasson, a Kodak engineer invented the first digital camera and Kodak marketing executives suppressed his invention because they understood what its impact would be on their highly profitable business—a case of conserving the past against the unknown benefits of a future technology. For me, this story sums up the short-sighted logic of capitalist “growth”. The Picture in Picture series is simply showing the means of photographic production.

AC: Can you dive a bit into the technical aspects of the works? Such as the gathering of raw material, software or hardware (in the wide sense; they could be thoughts and bodies) used, as well as the selection and editing process? What are some of the challenges you (and your team, or the collaborators you work with) have faced in realizing the works?

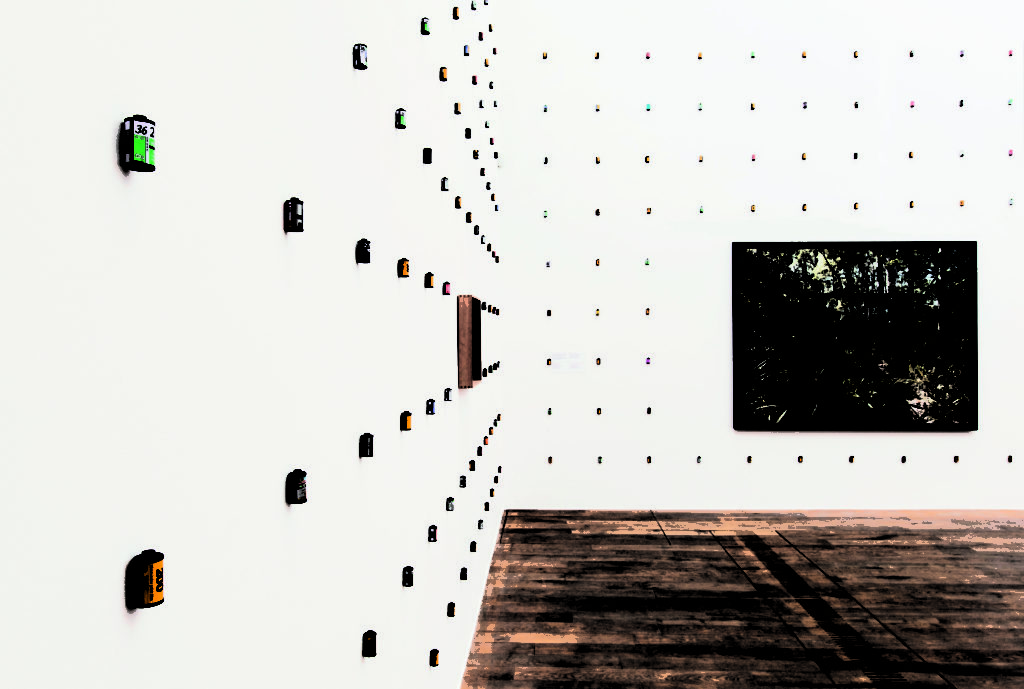

MD: There are too many…to simplify I will focus on one particular work. In KODAK (Four Dimensional Community) (2016) for example, the original negative is mounted in the center of the image surrounded by two successively larger prints, one gloss and the other matte. This is negative film no longer produced by Kodak— the end of analog photography being a significant aspect of the backstory. On a material level, the black surrounding of the film frames is prominent, emphasizing the printing process and displaying its starting point, the film ‘Kodak 160VC’. The layout of the three images replicate the relative positions of the negative and the prints inside the darkroom under the enlarger, giving the effect of a zoom—in time and space—traveling from print to negative, or perhaps vice versa. The challenge here was to show here how the work makes its own process of production visible, and how it references the economic and social frame that makes this process possible. Paradoxically, my conceptual reflection on the material process of reproduction produces a one-off art work that flirts with aura.

AC: Can you tell me about the relationship you want or aim to have with the viewer? Is your work a sort of a ‘gate’ although extremely subtle— which the visitor could go through but also miss, or is the viewer able to move from and to, around it—or beside it, or between it—but not really see it, or experience it from an ‘external’ point of view? In other words, is the work meant to be ‘faced’ so to speak? What is the underlying approach to this relationship with the viewer?

MD: It is an essential element of my process. Thinking about the viewer is how I remain focused on what is important. What I mean by this is that I think about the function of the viewer not only when I make individual photographic works which seem to come in one of the three approximate sizes (hand, head, and body) but when I conceive installations. The architecture of the exhibition hall determines what is possible in terms of scale, experience, and affect. What I try to do is activate the space in a way that is always specific. In the past, when I tried to repeat the same approach, I failed. Basically, every space has its own unique economic, psychological, social, political context, and it should be treated like that. When I say this, I do not mean that the same work can be shown in different spaces; it simply means it needs to be shown differently to provide generous experiences. The world right now is too absurd and too egomaniacal to disturb people with my ‘extreme’ art. I really do not care to do that at all. It is not fashionable at all, but I am interested in art experiences that can offer empathy, dignity, and mystery. If this is too utopian, I really do not mind.

AC: Tell me a secret about your work. Even a small one.

MD: I will tell you a secret about my life: my mother is a shrink. And here is another secret: my brother is a shrink too.

Mladen Bizumic (b. 1976, New Zealand) lives and works in Vienna. His work begins from a deceptively simple question: “What is photography?” While not the first to ask it, Bizumic offers an original and complex answer that unfolds itself between two sets of terms—analog and digital, modernist and conceptual. Among others, Bizumic has held solo exhibitions at MOSTYN, Wales, Georg Kargl BOX, Vienna, Zamek—Centre for Art, Poznan, the Salon of the MOCA Belgrade, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington, Govett Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, ARTSPACE, Auckland and other venues. His work has been shown in the 9th Lyon Biennale, 10th Istanbul Biennale, the 2nd Moscow Biennial, MAK—Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Leopold Museum, Vienna, KM—Künstlerhaus Halle für Kunst & Medien, Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz, Zacheta National Museum, Warsaw, and Foundation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris.